Flowing along south of Buenos Aires, Argentina’s capital city, the Matanza Riachuelo River leaves one of the world's most polluted urban areas and empties into the River Plate. To remediate this hazard, a $1.25-billion system now under construction will channel pre-treated wastewater to the end of a 12-km outfall into the River Plate, where Italian engineers deployed innovative pipe jacking equipment to push effluent riser tubes up though some 30 meters of riverbed.

It took two years for Milan-based outfall contractor Webuild S.p.A. to develop vertical pipe jacking rigs able to operate inside a tunnel. The undisclosed investment was made to replace the owner’s option of forming the risers from the river surface, says Nicola Valiante, the contractor’s head of design. Marine work can be “highly risky in terms of safety and construction schedule,” he adds.

Aimed to connect more than four million Buenos Aires citizens to sewers, the project includes a network of collector tunnels on the Riachuelo’s left side, a wastewater treatment plant at the port’s south dock and the outfall.

The project’s owner, the utility Agua y Saneamientos Argentinos S.A. (AySA), originally planned to get the system working next year. But full operations are not expected before 2023, according to program director Marcela Alvarez. The project's two tunneling contracts have made “good progress” while the treatment plant has had “significant delays including change of contractor,” she adds.

Set “in locations of challenging urban and underground settings”, the project was tricky, according to the World Bank, which is providing loans for the tunneling work. Because of cost hikes, it raised its contribution by nearly 40% last year to $850 million, according to Alvarez.

Then the pandemic struck, halting work on the program for about six weeks, says Alvarez. Altogether, the virus is contributing to delays in the contracts ranging from three and six months, she adds.

Plant Contractor Replaced

Work at the treatment plant ground to halt in late 2018, when the contracting joint venture of local firms ran into financial difficulties, with only 11% of the work done, according to the World Bank.

The joint venture was replaced in June 2019 by Italy-based Fisia Italimpianti S.p.A., which secured a 36-month contract now valued by AySA at $300 million. The plant will mechanically remove solid and floating matter from 27 cu m per sec of wastewater before pumping it to the outfall.

Wastewater to be treated at the plant will be collected by a system of shafts and tunnels being built by a joint venture led by Italy’s Ghella S.p.A under a $450-million contract. The work, begun in January 2015, covers more than 16 km of sewers, including a 9.5-km-long, 3.2-m-dia stretch followed by roughly 5 km of 4.5-m-dia section. The last stretch holed through at the plant this October.

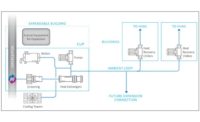

From the plant, AySA originally planned a 10.5-km-long, 3.8-m-dia outfall tunnel around 35 m below the River Plate bed. It was to terminate at a shaft to the river surface. From near the top of the shaft, a 1.5-km-long shallow pipeline was to be placed in sections on piled foundations within a pre-dredged trench in the riverbed. Short stainless steel risers were to be fixed to the pipeline.

But outfall contractor Webuild devised another plan. When it started work on its contract, also in January 2015, Webuild proposed vertically pipe jacking the 34 risers from inside the end of the outfall, eliminating the river shaft and most of the offshore work. It would involve lengthening the tunnel to 12 km and widening it to 4.3 m dia to provide more working space.

Alvarez was surprised by the proposal, which called for inserting about 1 km of steel tube in 650 sections through some 30 m of seabed. Preventing leaks and ensuring a 1 degree vertical tolerance were among the main goals, notes Valiante.

AySA approved the concept “due to the significant reduction of risks, and contingencies that were eliminated or reduced,” recalls Alvarez. Webuild embarked on “an extensive development of engineering, risk matrices, material tests, ending with full-scale tests in the supplier's factory, reproducing the installation conditions in the site of the works,” she adds.

With a current estimated value of $500 million, the outfall contract was on a re-measurement basis with detailed design by the contractor. But after AySA accepted the revised riser plan, that part of the work was converted to design/build, explains Valiante. Webuild is in a joint venture with its U.S.-based affiliate S.A. Healy Co. and locally-based José J. Chediack S.A.I.C.A.

Full-Scale Pipe Jacking Model

Pipe jacking development work started in Webuild’s design department where six people spent half their time on the project, says Valiante. As design advanced, the team called in other relevant disciplines from within the group and outside, while liaising with site staff in Buenos Aires. From time to time, the engineers drew in staff unfamiliar with the machine to validate their work, he adds.

After an extensive testing program, including a 16 m tall full-scale model, Webuild commissioned two machines in July 2019. The rigs arrived in December 2019, just after the contractor had completed the outfall tunnel.

Webuild started riser installation early last September and its two rigs finished work in just under two accident-free months, according to Valiante. At best, one rig installed an entire riser in a day, he adds.

Each riser tube was jacked up in 18 short sections with up to 200 tonnes force through openings in tunnel lining keystone segments. The jacks thrust the 71-cm-dia tubes vertically through four layers of dense sand, silty sand, clay and silt and unconsolidated clay. Ground above the leading pipe was fragmented by high pressure water nozzles in a displacement head. Displaced soil was piped down the riser for disposal.

Concerned that cutter nozzles could become clogged by hard grout around the tunnel segment, Webuild designed a mix that stayed plastic for six months, says Valiante.

The investment in developing the unique machine would have been high, believes Graeme Montieth, a tunneling specialist and secretary of the U.K.'s Pipe Jacking Association. Webuild "managed to make a bespoke rig that can work within a…tunnel,” he says. And “they built and tested the whole system before putting it in. The testing rig is a bit of a triumph,” he adds.

The vertical pipe jacking method “is very competitive” with traditional construction, says Valiante, who will not disclose the machines’ development and manufacturing costs.

From the owner’s perspective, the innovation came free of charge. “The final cost of the outfall …has remained practically unchanged, including the variant of its construction methodology,” adds Alvarez.