Final Agreement Signed for $16B Texas High-Speed Rail Project

Image courtesy of Texas Central

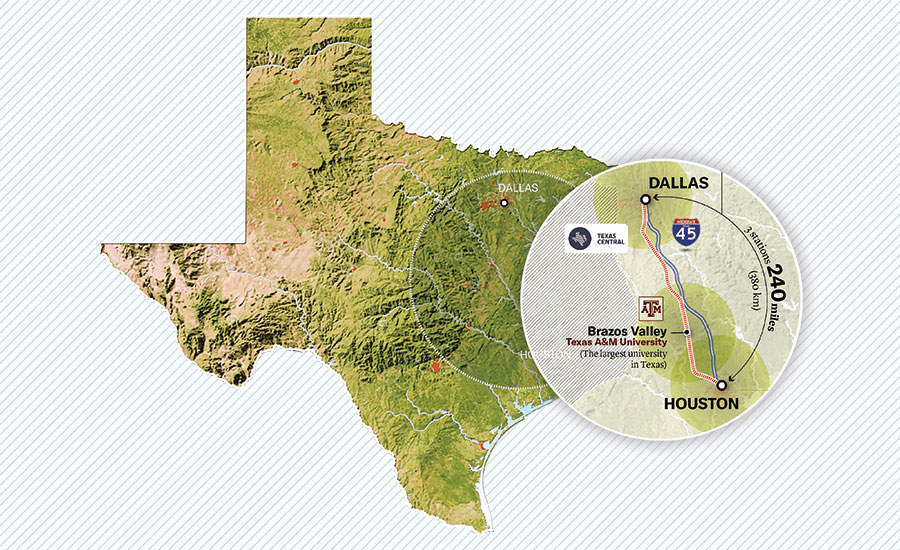

Nearly two years after first awarding a design-build contract for its privately funded high-speed Dallas-to-Houston railway, Texas Central Railroad LLC announced that the final project agreement has been signed, finalizing its cost at $16 billion. The agreement, with Lane Construction Corp. and its parent and joint-venture partner, Italy's Webuild Group, moves the project to the advanced design stage, with construction now expected to start in late 2021 or early 2022.

The contract agreement follows a June 18 decision by the Texas Supreme Court not to hear landowners' appeal of their eminent domain lawsuit, although other challenges remain. After full notice to proceed, the project will have a six-to-seven-year base construction schedule, Erin Ragsdale, Texas Central spokeswoman.

The final contract states that Lane and Webuild will execute the project's heavy construction work, and design and build the track system's 236 miles of alignment, along with train stations, and other buildings and facilities. The companies also will provide maintenance and equipment services.

Almost half of the railway will be elevated to reduce impacts on residents and landowners, the team says.

“We are excited to be part of this historic project that will bring high-speed rail to the United States,” said Mark Schiller, Lane Construction president and CEO, in a statement. “It’s a true milestone for our country’s sustainable transportation infrastructure.”

Cost Up as Scope Defined

When the Lane-Webuild JV was awarded the project in 2019, the contract value was estimated at $14 billion.

“The value of the contract has increased because the project scope has been more defined, including geotech, refinement of the specification requirements—ballast, as an example—additional watershed management requirements and investments, additional utility relocation work, and most importantly, additional work related to reducing impacts on land owners and residents of the counties the train will traverse—for example, reducing the road over rail passes from 46 to 11 and additional road work improvements,” Ragsdale explains.

While the pandemic factored into the length of time between the award announcement and the final agreement, refining the scope of work was the most significant cause, she says.

Texas Central reached several major regulatory milestones during that time, including release by the U.S. Dept. of Transportation’s Federal Railroad Administration of final specific safety rules for the line and its Record of Decision, Ragsdale says.

The rail system is based on Central Japan Railway’s Tokaido Shinkansen system and will carry travelers at speeds of up to 200 miles per hour, making the trip from Dallas to Houston less than 90 minutes in length—with one stop in the Brazos Valley. The company expects to transport more than 400,000 passengers daily, which should help cut greenhouse gas emissions by an estimated 101,000 tons annually by reducing car travel.

“We have all the players we need to execute the construction and operate the train,” Ragsdale says. “In addition to Webuild, we announced Kiewit Infrastructure South Co. and Mass. Electric Construction Co. as a partner [to install the line's core electrical systems] and Suffolk and Matthews Southwest as our station construction partner."

Texas Central currently has control of more than 600 parcels of land, representing about 40% needed for the railroad, Ragsdale says.

New Legal Challenges Emerge

The Texas high court declined to hear a lawsuit (James Miles v. Texas Central) that challenged Texas Central’s ability to use eminent domain to build the railway. The plaintiff landowner won the case at trial court in 2019, but that decision was overturned in the Texas Court of Appeals in May 2020.

The appeals court concluded that Texas Central qualifies as an entity entitled to use survey and eminent domain authority under the Texas Transportation Code, Texas Central said in a statement. The high court's denial of review "should put an end to over five years of contentious litigation," the developer said.

But opposition remains. During testimony to Congress in May 2020, Waller County Judge Trey Duhon III said that if the line "is built, the project will hit rural and minority communities along the proposed route like mine the hardest, including the other end of the proposed route of south Dallas where entire low-income minority neighborhoods would be displaced because only one route was ever considered.”

In another lawsuit filed in April against the federal transportation agencies by nonprofit organization Texans Against High Speed Rail, six Brazos Valley counties and several landowners, plaintiffs contend that the railroad agency's environmental impact review did not consider that railway tracks will only allow Texas Central trains to run and would not support links to the region's existing railway network. Developer Texas Central was not included in this lawsuit.

Texas Central predicts the project will provide economic impact of about $36 billion over the next 25 years and create 17,000 direct jobs during the six years of construction and more than 1,500 permanent jobs when train service becomes fully operational. The developer anticipates use of $7.3 billion worth of materials from U.S. suppliers across 37 states.

Next steps for the project will be to secure permanent funding and to work with applicable agencies to advance to the construction phase, Ragsdale says.

The railroad "has already secured letters of intent from banks in Japan and Europe, reflecting the financial viability of the project, and now is working toward achieving formal commitments from these entities, as well as others in the United States," she adds. "Exact timing of execution will depend on how fast the formal commitments are secured.”

Names of current investors are not being shared publicly and no state funding will be involved. “Outside of that, Texas Central is constantly evaluating all financing options available to us,” says Ragsdale.