ENR Best Projects

Moynihan Train Hall Is Open to the Light

One-acre, 92-ft-high glass canopy skylight atop Moynihan Train Hall is highlight of $1.6B Penn Station add

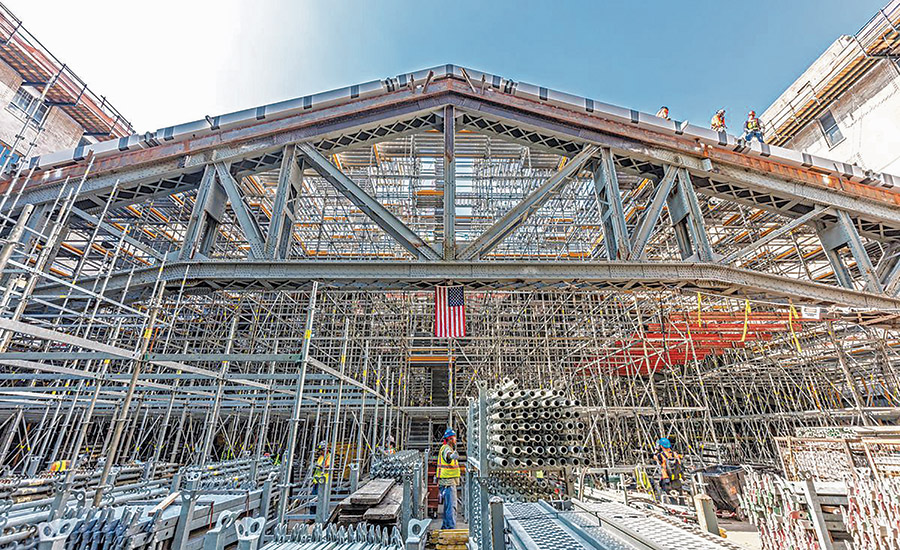

This aerial view shows the massive scale of the undertaking to create Moynihan Train Hall.

Photo by Dave Burk and Aaron Fedor/Empire State Development | SOM

Moynihan Train Hall

New York City

BEST PROJECT, AIRPORT/TRANSIT, and Award of Merit, Sustainability

OWNER:New York State Urban Development Corp. (d/b/a Empire State Development) in a Public-Private Partnership With Vornado Realty Trust, The Related Cos., Skanska, the MTA, the Long Island Rail Road, Amtrak and the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey

LEAD DESIGN FIRM: Skidmore Owings & Merrill

GENERAL CONTRACTOR: Skanska

STRUCTURAL ENGINEER: Severud

MEP ENGINEER: Jaros, Baum & Bolles

PROGRAM MANAGEMENT: WSP USA

SKYLIGHT STRUCTURAL ENGINEER: Schlaich Bergermann Partner

The one-acre, 92-ft-high glass canopy roof and skylight atop New York City’s Moynihan Train Hall was always going to be a centerpiece of the $1.6-billion transit center that expands capacity for the bustling Pennsylvania Station across the street in midtown Manhattan. But among many feats in transforming the 108-year-old James A. Farley Post Office into a 255,000-sq-ft passenger hub, the soaring glass structure arguably also served as the project’s design and construction highlight.

Turning the old mail sorting area of the classic McKim, Mead & White-designed structure into a sky-lit hall for rail passengers epitomized the project’s central tension—carving an innovative and functional facility out of a landmarked building built for an entirely different purpose, while balancing historic preservation with modern design.

The final achievement won high marks from the 2021 Best Project judges for teamwork, craft quality, function and aesthetics on a complex project led by Skidmore Owings & Merrill as architect, Skanska as construction manager and WSP as program manager.

The team also included Severud as structural engineer and Jaros, Baum & Bolles as MEP engineer; the developer partnership of Empire State Development Corp., Vornado Realty Trust and the Related Cos.; and key stakeholders such as Amtrak, Long Island Rail Road, the Metropolitan Transportation Authority, the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey and New Jersey Transit.

Erecting the skylights was a complex task aided by a key decision to remove north-south trusses under the old roof but keep three 150-ft-long east-west trusses to enable the old Farley mail sorting room to support the new canopy, says Marla Gayle, SOM managing principal.

“When the demolition began and [the megatrusses] were finally revealed, everybody was blown away with how unbelievably spectacular those were—the kind of engineering that usually happens on bridges, and certainly nothing that could ever be replicated today,” she says.

Inside the 31st Street doors is Elmgreen & Dragset’s “The Hive,” an inverted cityscape inspired by iconic buildings in New York City and beyond.

Photo by Dave Burk/Empire State Development | SOM

Enabling that effort was a clever logistics feature: installation of the “dance floor,” a temporary structural steel work deck where the sorting floor had been. That allowed demolition and construction for the skylight and train hall above the deck while work advanced below to fortify the train shed over underground tracks connecting to Penn Station.

“Skanska basically made an investment in their logistics,” says Doug Carr, Empire State Development’s executive director. “Skanska split the site into two—with skylight work and platform work occurring simultaneously, which was definitely a big portion of how we were able to accelerate construction.”

From the deck, the team reinforced the megatrusses, adding 3-in.-thick steel plate box beam supports across the tops. It also erected the canopy, a task—with Schlaich Bergermann Partner as skylight structural engineer and Seele as facade design-assist contractor—requiring 775,000 lb of steel, 2,200 glass panels and 2,936 aluminum and glass elements overall. The team used adjustable scaffolding and diagonal cable support systems to achieve exacting tolerances on the skylight’s four barrel-shaped catenary vaults, which have thicker glass panels at the edges to sustain greater loads but lighter ones at the 92-ft apexes.

The deck also helped the team conduct interiors demolition, abate asbestos and lead, rehabilitate mechanical and electrical systems, upgrade lighting, add structural steel reinforcement and ensure a safe site, which contributed to the project’s overall 1.88 recordable incident rate and lost-time rate of 0.23 across more than 6 million worker hours.

The train hall expands concourse and vertical circulation capacity and significantly improves station accessibility.

Photo by Nicholas Knight/Empire State Development

Majestic Utility

Moynihan Train Hall’s distinct character doesn’t detract from its purpose to expand concourse floor space by more than 50% at Penn Station, which serves 700,000 passengers daily, says the team. The hall houses ticketing and waiting areas for Amtrak and LIRR, improves access to nine platforms and connects to 17 existing tracks.

The new center also adds 730,000 sq ft of commercial office, retail and dining space; links to an MTA subway line; connects to a station entrance at Ninth Avenue; and links to a $220-million first phase of the Moynihan project, completed in 2017, that built a western concourse for Penn Station and enhanced passenger circulation.

The larger final phase, which broke ground in June 2017, not only finished on time in December 2020, but also at budget on a project funded with $630 million from the joint venture developers, $550 million from New York state and $420 million from Amtrak, MTA, Port Authority and a federal grant.

The team says it achieved those goals despite the disruption caused by COVID-19, with a particularly difficult time in March 2020 when it faced both a 10-day pandemic work stoppage and the suicide of Michael Evans, former president of the Moynihan Station Development Corp.

“It was a very low point for the team and a lot of sadness,” says Shaun Pratt, project director at WSP. “For us to regroup to finish the project for New York and for Michael Evans, it was a great accomplishment.”

The project also notched an impressive accolade—a LEED for Transit Silver certification from the U.S. Green Building Council for its use of natural lighting, recycled materials and low chemical-emitting products; intermodal connections to other transportation; innovative MEP infrastructure; and restoration of historic features.

“We were the first in the world to receive that recognition,” Pratt says.

The new train hall’s main concourse is located in the old post office’s former mail sorting room.

Photo by Dave Burk and Aaron Fedor/Empire State Development | SOM

Preservation and Adaptation

A central theme was finding the right blend of adaptive reuse, historic preservation and modern systems. The main hall’s combination of rehabilitated original columns, contemporary digital passenger navigation displays and newly added but classic quaker gray marble is emblematic of striking that balance.

The overall effort featured restoration of 200,000 sq ft of stone facades, 700 windows, a copper roof and terra-cotta cornices; renovation of 1.4 million sq ft of former office space; and the addition of the modern canopy, public art and furniture.

“It was the transformation of a structure designed as a post office and largely an industrial building, mostly a mail sorting facility ... into a contemporary civic space and public transportation venue,” says Jon Cicconi, SOM senior associate principal.

The team proceeded not only with respect for the original structure but a desire to enhance it, says John Sullivan, senior vice president of operations for Skanska USA Civil.

“Some of the original columns were going to be clad in metal panels or stone, but during demolition the project team decided to leave the columns exposed and reuse existing marble on partitions,” he adds.

That respect led to determined efforts to harmonize new features and fit security, mechanical and other building systems behind ceilings and walls, Gayle notes.

“Things like the canopies … were a very delicate touch, so that the whole exterior continues to read in a very similar way to the original building that McKim, Meade & White had constructed,” she says. “Integrating 21st-century technologies into a 100-year-old building was certainly a challenge.”

The project was built from the top down, starting with demolition of the original sorting floor. Work included penetrating the concourse floor and 12-ft transfer girders to install 11 platform escalators.

Photo courtesy Skanska

Technical Hurdles

Another thorny task was working around remaining operations of the U.S. Postal Service and the rail tracks below, Carr says.

“We were taking over portions of the building and phasing construction,” he says. “So we were constantly working around the Postal Service during the construction phase.”

Work to reinforce the train shed was also meticulous, Carr adds. “The track outages were very highly choreographed—weekend outages starting at 10 p.m. on a Friday, taking tracks out of service and working 24/7 and returning tracks at 5 a.m. on a Monday,” he says.

The team worked hard to avoid disruption to regular service on the 30 active rail tracks, Sullivan says. “Despite 108 weekend shutdowns spread out over two years, never once were the trains of Penn Station’s four operating railroads delayed,” he says.

The team also had to penetrate the concourse floor and 12-ft transfer girders to install 11 escalators to the passenger platforms below as well as add 15 new elevators and improve or extend 10 others.

Moynihan Train Hall’s crowning glory, shown while under construction, required reinforcing the existing 150-ft trusses and installing the barrel skylight.

Photo by Nicholas Knight/Empire State Development

Strong Communications

One of the design-build project’s quiet achievements was a high level of coordination among the stakeholders. Various participants established protocols to ensure maximum levels of collaboration and communication with other team players on a project with an aggressive schedule and various overseas suppliers.

The team was able to avoid pitfalls with the proactive approach, Carr says, noting that each rail agency had different technology, operations and building systems.

“There was definitely ongoing coordination through the entire project,” he says.

The team also implemented a rigorous scenario testing process to ensure facility readiness, planning a program 18 months in advance to first conduct small trial runs and then a large-scale event in early December 2020 with 150 people simulating a normal day of operations, Pratt says.

The goal was to flag potential problems and get project participants to focus on the commuter and worker experience, says Kelly Pilarski, WSP project manager and lead engineer.

“It really forced everybody that was going to be an end user for this facility to think about what they needed, and how far in advance of opening they needed to test and run trials and to think about how operating procedures should work,” she says.

Finished Features

The Moynihan Train Hall houses other notable elements, both visible and hidden. One is a radiant in-slab heating and chilled-water cooling system that creatively addresses a space where it would be difficult to install or control temperature with traditional HVAC units.

The hydronic system concentrates on floor spaces where people circulate, rather than the air above, saving on costs of regulating temperature in areas no one will occupy. The system’s tubing and embedded sensors also facilitate individual control of 27 zones across 78,000 sq ft of the concourse, allowing for different settings in each “microclimate,” such as areas bathed in sunlight versus shaded spaces, says Ryan Stecher, JB&B associate partner.

The system also enables precise calibrations near entrances, where cooling on a humid summer day might otherwise form condensation—and a slippery walk—on the marble floors, he says.

“The goal was to put the heating and cooling right where the people are,” Stecher says. “It’s absolutely something we should see more of in the city.”

Visitors also will be able to appreciate another signature element—prominent public artwork. Art elements include “The Hive,” a ceiling-hung sculpture of an inverted cityscape by Elmgreen & Dragset; an LED-lit stained glass and steel structure depicting New Yorkers in modern dance poses by Kehinde Wiley; and a series of photo panels harking back to the original Penn Station by Stan Douglas.

Each piece required extensive effort not only for installation but also testing, Pilarski says. “The art in Moynihan is spectacular. It’s a destination in itself,” she adds.