Engineering Justice

Cincinnati Soccer Stadium Siting Raises Questions

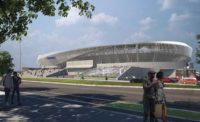

TQL Stadium, the home of FC Cincinnati, was built in an urban neighborhood to give the soccer venue a "European feel."

Photo by James Leggate

Cincinnati’s West End is a mostly Black neighborhood where, compared to the rest of the city, the median income is lower and the percentage of residents who rent is higher. So when FC Cincinnati, the city’s professional soccer team, chose the neighborhood for its $250-million TQL Stadium, it raised both hopes and worries about what would happen to the area.

The West End sits beside Over-the-Rhine (OTR), formerly also majority Black, where focused redevelopment has led to gentrification. U.S. Census Bureau data show that, from 2010 to 2020, OTR’s Black population decreased by 44%, while its white population grew by 74.9%. Opponents of the stadium project worried their neighborhood would undergo a similar change.

“That land will never go back to poor people, ever,” activist and local contractor Brian Garry said. “And the institutional creep is already happening.”

Garry helped some residents and business owners negotiate compensation from the team and from the city. One, restaurateur Monica Williams, was able to move her business to a building she bought in another neighborhood. But not everyone ended up in a good spot, Garry stresses. One former West Sider, Ken Rhodes, struggled to find a new home that would be accessible while using his wheelchair or walker, and ended up in what Garry calls “a crackhouse drug den” with “no security, no locks” in a food desert further north. In August, Rhodes died, possibly from COVID-19.

Related Links

New Era of Equity Is Blowing In

Righting Past Wrongs Through Equitable Development

Boston's Committment to Equity

Miami Residents Fight for High Ground

The West End has a history of being shaped by outside planning. It was home to 40,000 people in the 1950s— 85% of Cincinnati’s Black population. But mid-century urban renewal led to the construction of the Millcreek Expressway, now I-75, through the heart of the West End. Parts of the neighborhood west of the highway were razed, renamed Queensgate and redeveloped as an industrial zone. As of 2018, its population was down to 6,650 with a median income of $22,000. To build the stadium at the West End site across a street from OTR, a high school football field had to be relocated—FC Cincinnati paid for it—and several other buildings were demolished.

Dan Lolli, FC Cincinnati vice president of facilities and stadium general manager, says the team picked the site to create a “European feel” after also considering locations across the Ohio River and in Oakley, a wealthier and demographically whiter Cincinnati neighborhood.

“We kind of dropped a stadium in the middle of a neighborhood, but that’s pretty much par for the course over across the pond.”

In construction of the 26,000-seat stadium, FC Cincinnati hired minority- and women-owned businesses and other small business enterprises for 70% of project work. It worked with the community to identify ways to improve local quality of life, and is investing $50 million in things such as a youth soccer program, construction jobs training, a nonprofit that offers emergency housing assistance and $100,000 in annual grants for West End groups.

Additionally, Populous designed stadium height and orientation to minimize shadows on the surrounding area. The team has also avoided things such as late-night pyrotechnics, Lolli says. The stadium’s speakers were strategically placed to keep sound inside the building.

“We want to be good neighbors,” Lolli says. “And a huge part of my job is making sure that we aren’t just dropping a stadium in the middle of a neighborhood and not thinking about what was already here.”

But there are still concerns the stadium, which opened in May 2021, is only the beginning of a new wave of redevelopment that will price residents out of the neighborhood. One developer has already opened a soccer-themed bar across the street in OTR, and plans to build an 85-room boutique hotel next door that's slated to open in 2024. A real estate firm is advertising 110,000 sq ft of office space in a to-be-renovated former industrial building immediately north of the stadium that's planned to open in 2023.

Garry questions why the stadium couldn’t have been built where the city’s NFL, MLB and minor league hockey teams play.

“I mean, they’re building a parking garage on top of these people’s homes,” he says. “How many more parking garages do we need in this world?”