Spending New Funds Effectively Was Big Theme at TRB Event

With highway crashes costing Washington state taxpayers billions, beyond the human cost, its DOT is focusing on multimodal means of mobility.

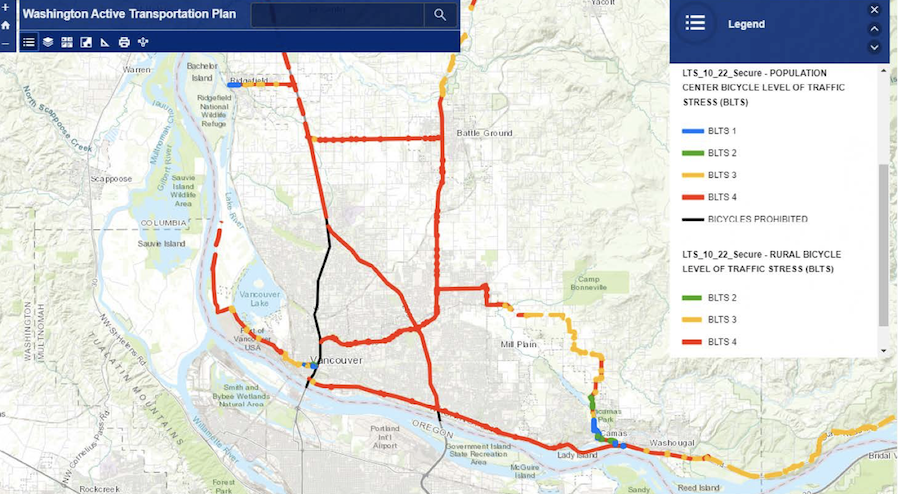

Graphic Courtesy of WashDOT

Attendees at the Transportation Research Board annual meeting debated whether the 2021 Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act and the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act can live up to lofty promises of delivering revitalized and resilient infrastructure, noting more challenges linked to changing rules and programs.

At the Jan. 7 to 12 event in Washington, D.C., discussions identified a variety of implementation issues—from changes in environmental regulation processes to eligibility and performance requirements for several discretionary grant programs, to coordinating infrastructure development with efforts led by other federal agencies.

“There’s a ‘Catch-22’ of building expectations that [the] law will fix everything, but there’s not enough money to do it,” observed Susan Binder, principal at Cambridge Systematics and former Federal Highway Administration deputy associate administrator for policy and governmental affairs.

Of particular concern is the pervasive effect of inflation and supply chain issues, which many fear will curb agencies’ project funding plans—a situation characterized by one audience member as, “more bucks, but the same bang.”

Binder admitted that meeting that political pressure won’t be easy. “We set up those expectations because of long-deferred money,” she said. “Now those chickens are coming home to roost.”

Former FHWA Chief Counsel Fred Wagner, now a partner at law firm Venable LLP, believes a divided Congress is unlikely to roll back IIJA funding. Still, the Republican-controlled House of Representatives is expected to scrutinize new grant programs closely tied to the Biden Administration’s environmental and economic policy goals.

Recalling the solar panel manufacturer Solyndra, which went bankrupt in 2011 after receiving more than $500 million in federal loan guarantees, Wagner said “they’ll be watching for any evidence of wasteful grants. That’s a major concern, as there are many start-ups involved in areas such as electric vehicles.”

Up and Running?

Also uncertain is whether bolstered transportation funding levels will be maintained when authorizations expire after 2026. Because the law did not address the federal gas tax, Wagner said general funds are being used to augment the Transportation Trust Fund.

“Will the funding still be there when these programs are up and running,” he asked. “We don’t know.”

Participants also discussed changes to the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) through past and current administrations. Ted Boling, an associate director on the President’s Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ), noted that it “now has two pots of money” thanks to the Inflation Reduction Act—including $32.5 million for NEPA investments and $70 million a year, for up to $350 million, to “carry out the mission” of actually obtaining permits.

Jomar Maldonado, NEPA associate director at the council, said that guidance in conjunction with the Office of Management and Budget to develop an efficient NEPA process will hopefully emerge this year. “We always said that if only we had enough money, we could move faster,” he noted. “Now we have the money, and we have to perform.”

Federal expectations related to greenhouse gas emissions and proposed new transportation projects will eventually include social cost estimates and the total lifecycle of the projects, predicted Boling.

New programs, including one for safe streets and roads and another for thriving communities, will receive “non-traditional” applicants that are not state DOTs, said Michael Drummond, an attorney-advisor at the U.S. Dept. of Transportation. These include state municipalities. Updating the process of receiving funds and streamlining environmental permits is akin to “remodeling the plane while flying it,” he said.

A panel of environmental compliance experts identified several other factors that have slowed the NEPA process—among them project complexity, agency workloads and staffing and fear of litigation. But the process should not be blamed when designs or political priorities change, the panel agreed.

In addition, recent efforts to accelerate the NEPA process may have done more harm than good.

Jack Allen, a veteran NEPA specialist at Avenue Consultants, Salt Lake City, said expedited delivery, succinct documents and concurrent agency reviews all have been part of the law since its enactment in 1970. He called efforts such as agency-developed NEPA templates “essentially commoditizing critical thought” in a process designed to make multidisciplinary decisions.

“NEPA doesn’t need to be changed, just done better,” he said.

Rethinking Risk

The evolution of alternative project delivery methods also evoked strong opinions. While more states consider collaborative models such as design-build, fear of the unknown can be hard to discard, they agreed. “You have to fall off the bike several times,” said Ananth Prasad, president of the Florida Transportation Builders Association. The former state DOT leader said “contractors who were once hesitant” about design-build “now love it.”

After years of experience, he said, Florida DOT is no longer shifting utility relocation risks to design-build teams and is rolling out a “right to rely” rule in which design-build teams can rely on the information they are provided when proceeding with a project.

Henry Patel, vice president of Kiewit Development Co., said the firm is adopting best project delivery practices from other industries, and now has over 2,000 designers to meet early engineering needs for design-build projects. He cautioned that contractors will include in their bids a “massive contingency” if they can’t price the risk. Moreover, when owners say a component has a small percentage of risk in a megaproject, “a small percentage of a large project is still large.”

Panelists concurred that there should be honest conversations about risk and risk-sharing rather than foisting it entirely onto the party that supposedly can handle it; capping the risk is also desirable. Ural Yal, senior vice president with Flatiron Construction, said, “The open-ended nature [of risk] is what scares us.”

John Carlson, strategic business officer at Sundt Construction, added that while the firm has taken on such risks as environmental permitting and rights-of-way, it is always while working together with the owner.

Up in the Air

Several TRB panels offered insights into transportation’s not-too-distant future. Among the many topics were incorporating drones and other unmanned aircraft systems (UAS) into airport operations and master plans, use of satellites and remote sensing to detect potential embankment and ballast slides along rail lines and the potential applications for super-elastic shape-memory alloys (SMAs) in concrete reinforcement.

One transportation facet of the future taking longer to be fulfilled than originally expected are autonomous vehicles, with development beset in recent years by high-profile technology failures and cooling interest among automobile manufacturers.

Steven Shladover, research engineer at the University of California’s PATH Program, said that AV developers have yet to achieve the benchmark of a safer driving environment than that found today—a goal critical to earning the trust of both regulators and the public.

For example, choosing scenarios to prove AVs’ ability to avoid and mitigate the severity of crashes is difficult due to how the wide variation in conditions and scenarios available that can be tested at proving grounds or via validated simulations.

“Safety is hard to do,” Shaldover said.

While the session did not address potential infrastructure upgrades to accommodate the broader deployment of AVs, states remain eager to attract AV-related research efforts, with more than 20 having approved some form of testing and deployment activities.

Edwin Olson, CEO of AV consultant May Mobility, also cited a movement among cities to consider the technology when planning for a more transit-oriented future that includes “robo-taxis” and other driverless mobility options.

“Cities have been built around car ownership and want to break that cycle,” he said.

State of the State DOTs

Roger Millar, Washington State Dept. of Transportation secretary and new president of the Association of American State Highway and Transportation Officials, described its strategic plan to address safety, sustainability and mobility. Emphasizing multi-modal and high-tech solutions, he said highway crashes in the U.S. cost $1.14 trillion a year. In Washington, congestion cost taxpayers $2 billion last year, while accidents cost $18.5 billion. With only $2.5 billion in state funds allocated for mobility and $50 million for safety, “our priorities are wrong,” he said.

Diane Gutierrez-Scaccetti, New Jersey State Dept. of Transportation commissioner, said the agency launched a pilot at Princeton University for “exclusive walk phase traffic lights,” in which a pedestrian-only traffic phase is included in the cycle. She also cited use of foamed glass aggregate on a Route 7 improvement project as the use of coconut-fiber “blankets” to stabilize slopes. A planned Route 3 bridge over the Hackensack River will include the possible application of “ultra light rail,” she added.

Some day, state DOTs will instead be called “departments of mobility,” Gutierrez-Scaccetti said.

Louisiana Dept. of Transportation and Development Secretary Shawn Wilson revealed a collaborative DOT vision with six “aspirational” goals for transportation: safety and security, accessibility and affordability, seamlessness and reliability, healthy and thriving users, clean and sustainable, and agility and resiliency.

In Delaware, “we are focused on people, not highways,” said Nicole Majeski, state DOT secretary. The agency has established partnerships with various counties to create 11 transportation permit districts so as to better coordinate transportation planning with land use.

Carlos Braceras, Utah DOT secretary, echoed the emphasis on people rather than on moving people, saying the DOT’s vision is to help residents create “the community of your dreams.”

“Every project we do focuses on connecting communities,” he said.

The event also coincided with the Biden-Harris Administration release of the U.S. National Blueprint for Transportation Decarbonization. Developed by the U.S. Departments of Energy, Transportation, and Housing and Urban Development and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, it aims to cut all greenhouse gas emissions from the transportation sector by 2050, secure a 100% clean electrical grid by 2035 and reach net-zero carbon emissions by 2050.