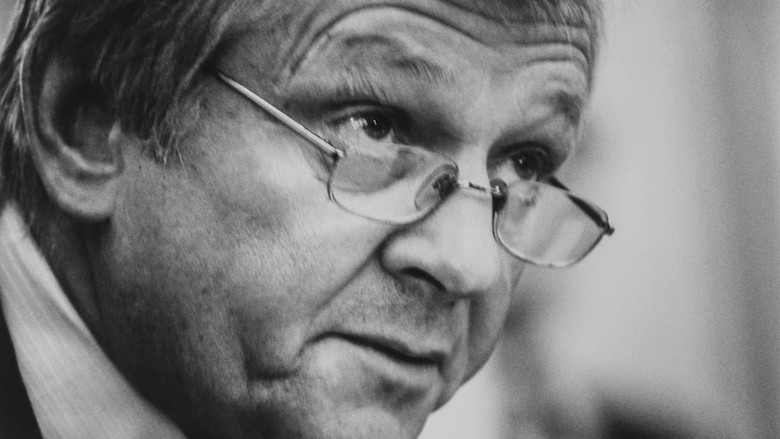

Former congressman E.G. (Bud) Shuster, a Republican from western Pennsylvania who wielded great power over federal infrastructure legislation as chairman of the House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee, died on April 19 in Everett, Pa. He was 91.

Shuster served in the House from 1973 to 2001. His peak impact on legislation came from 1995 through 2001 when he chaired the "T&I" Committee. That panel had, and continues to have, broad jurisdiction over infrastructure programs, including highways, transit, aviation, water resources, wastewater treatment and federal buildings.

A committee spokesman confirmed that Shuster died at home after experiencing complications stemming from recently breaking a hip.

Current committee Chairman, Rep. Sam Graves (R-Mo.), called Shuster “a legend,” adding in a statement, “He was a masterful legislator and one of Congress’s most effective advocates for America’s transportation and infrastructure.”

Rep. Rick Larsen (Wash.), the committee's top Democrat, called Shuster “a force on Capitol Hill for America’s transportation system." Larsen added, "His deep understanding of policy, willingness to work across the aisle, and ambitious vision for our country’s infrastructure allowed him to notch impressive legislative accomplishments during his time at the helm of our committee.”

Transportation Equity Act

During his chairmanship, Shuster shepherded the 1998 Transportation Equity Act for the 21st Century (TEA-21), which authorized $218 billion over six years for highway and transit programs. It included a "firewall" to ensure that Highway Trust Fund receipts would go for infrastructure.

He also led the efforts that produced a multi-year Federal Aviation Administration measure in 2000 and Water Resources Development Acts in 1999 and 2000. The water resources bills authorize funds for U.S. Army Corps of Engineers river locks and dams and other civil works projects.

As chairman, Shuster's clout was underscored by the size of the committee, which grew to be the largest in the House. That contingent gave him a bloc of votes to count on when legislation came to the floor.

Shuster also was a champion of funding earmarks–or demonstration projects, allocations in bills that ensured their congressional sponsors would vote his way.

Ethics Cloud in 2000

But Shuster's tenure was clouded in October 2000 when the House ethics committee voted to sanction him, issuing a "letter of reproval" stating that he had violated House rules and "engaged in serious misconduct."

The ethics committee said Shuster knowingly allowed his former chief of staff, Ann M. Eppard, to communicate with him in his official capacity during the period in which former House staffers are barred from lobbying House members for whom they had worked.

The ethics committee also said Shuster violated House "gift rules" by accepting some expenses for a trip he and his family took to Puerto Rico.

Shuster strongly defended his actions, saying they "had complied with the law," and he criticized the ethics committee's sanction as "overkill."

But the letter notes that as part of a negotiated settlement, Shuster admitted to a "statement of alleged violation" in which he agreed that his actions "did not reflect creditably" on the House.

On Jan. 4, 2001, Shuster announced that he would retire as of Jan. 31, after beingh re-elected the previous November.

He had been asked to step down as T&I chairman because of House GOP limits on chairmanships. Shuster said that recent "health scares" involving himself and his wife "have caused me to reevaluate my priorities and responsibilities."

Bud Shuster's son, Bill, won his father's seat in Congress in 2001 and served for more than 17 years. In 2013 he became chairman of the T&I Committee.

In January 2018, Bill Shuster announced he would retire the following year, when his term was up. He also faced the House GOP's six-year limit on chairmanships. Bill Shuster now is a senior policy adviser with law firm Squire Patton Boggs.

Story corrected on 4/25/2023 to state that the TEA-21 law's total authorizations were $218 billion. The original story used the figure of $198 billion, which was the law's guaranteed funding.