Foundation Repairs

After 15 Years, Settlement Arrested at San Francisco's Millennium Tower

Contractor completes transfer of building loads to new piles to bedrock

The synchronous jacking of 18 new perimeter piles, to relieve loads on the 645-ft-tall building's original mat foundation, went off without a hitch, says the engineer.

Photo by Ronald O. Hamburger

After overcoming several snags, the team for the voluntary effort to stem future significant settlement and tilting at San Francisco’s 645-ft-tall Millennium Tower has declared the project a success, now that loads have been fully transferred to 18 new perimeter piles driven to bedrock.

But the victory for the team implementing the $100-million foundation upgrade was hard won, coming only after unanticipated accelerated movement during pile production forced a moratorium to alter pile-driving methods, which in turn motivated a redesign to put the fix back on budget and schedule.

As of June 19, “survey data reveals that settlement has indeed been arrested, as was the primary project objective, and in fact, the building has risen slightly out of the ground,” says Ronald O. Hamburger, the engineer-of-record for the fix and a consulting principal with Simpson Gumpertz & Heger (SGH), working for Millennium Tower, a residential condominium association.

Further, the building has begun slowly to recover the 30 in. of tilt to the northwest that had occurred over 15 years, adds Hamburger, who has been working on the voluntary foundation upgrade, intended to arrest significant future settlement, since 2014.

The city’s independent team of engineers overseeing the fix since the beginning of design, concurs with Hamburger, says Gregory Deierlein, the chair of the Dept. of Building Inspection's engineering design review team (EDRT). “Now that the foundation is in place and the piles are stressed, I think we’ll find the basic design of the retrofit was well-conceived,” says Deierlein, who was on site June 19 for the final phase of pile jacking to transfer loads to the new piles. “We expect to see the effect of the stressing on the settlement and tilt” over time, he adds.

Building Remained Occupied

There was no concern, on the part of the city or Hamburger’s team, about the safety of the 58-story building, which remained occupied throughout the fix that began in the fall of 2020. Based on early studies by SGH, reviewed by the EDRT, to assess the building’s performance during an earthquake, “there was never any doubt about the building’s structural integrity,” says Deierlein.

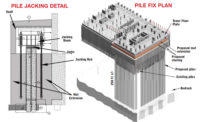

The revised upgrade involved transferring a portion of the building weight, in stages—via 18 new perimeter piles socketed into bedrock—from the existing foundation system—a central-core reinforced concrete mat bearing on piles that do not go to bedrock. There were 52 new piles in the original repair scheme.

The redesign was a consequence of additional tower settlement triggered by the initial pile-driving work, executed by Legacy Foundations, a division of Shimmick Construction Co. Inc., which is the prime contractor.

The fix settlement and the overall settlement, which began during construction in 2008, is attributed to the densification of the Marine/Colma sands below the tower, says Hamburger.

Of the 30 in. of tilt to the north and west, as measured at the roof horizontally, 7 in. occurred during the pile upgrade work, says Hamburger.

“We did not anticipate the pile installation would cause additional movement, but we were proactive about it,” says Hamburger, who halted the repairs, voluntarily, in August 2021, so the team could develop a revamped pile-driving method that would not accelerate settlement.

The pile production problems, which were solved, nevertheless “burned a significant amount of schedule and money,” says Hamburger. “The homeowners asked us to scale down the upgrade” to get back on track, he adds.

The engineer studied as few as six and as many as 52 piles and settled on 18, which accomplished the project objectives and allowed work to be completed within the available time slot, Hamburger explains.

Last August, after more than six months of scrutiny, the San Francisco Dept. of Building Inspection issued a revised building permit for the 18-pile scheme.

Like a Bumper Jack for a Flat Tire

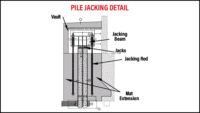

The fix, likened to putting a bumper jack next to a flat tire, relied on drilling and jacking the 18 perimeter piles—socketed more than 30 ft into rock that starts 220 ft below grade—under the sidewalks along Mission and Fremont streets. The piles, six along Mission on the north side of the tower and 12 along Fremont on the west side, support a new mat extension, known as a collar, that ties into the original mat.

In January, after casting the collar along Mission, Shimmick’s Legacy began the phased load transfer operation by synchronously jacking the six piles along Mission to 500 kips each. The purpose was to stabilize the building while crews excavated along Fremont to cast the mat extension.

Crews cast the two Fremont extension mats, one at the north end of the tower and the other at the south, on Saturday, June 3.

On Saturday, June 10, Shimmick initiated the second stage of the load transfer, which consisted of bringing the 12 piles along Fremont up to 500 kips each. The pace was 100 kips per day for five days, says Hamburger.

On Thursday, June 15, Shimmick's Legacy began the final stage of load transfer, which consisted of raising all 18 piles to 1,000 kips each, again 100 kips per day.

Building Surveys

Immediately prior to and after application of jacking, the project team conducted a building survey including recording the elevations of key locations on the existing and new building mats, horizontal deflection data from prisms mounted on the façade and elevations of the pile heads.

“I reviewed this data, daily, before authorizing the next load increment,” says Hamburger.

Shimmick’s Legacy completed the load transfer operation on Monday, June 19, without incident, says Hamburger. “We anticipate this tilt recovery will continue, slowly over a period of many years,” he adds.

The team forecasts the conclusion of the entire operation by late August or early September. Remaining work includes casting of concrete vaults around the pile heads—which is already in progress with formwork and reinforcing steel in place; backfilling around the vaults; and restoring the streetscape and utilities.

Looking back, Hamburger says the foundation upgrade team, which included the homeowners’ association, the contractor and the designers, was “always able to work together" to figure out the best path forward.

“There was never any talk of lawsuits,” he adds. “It all worked well,” in the end.