Sustainability

Seattle's Living Laboratory Tests Novel Low-Carbon Building Materials

September 13, 2023

Sustainability

Seattle's Living Laboratory Tests Novel Low-Carbon Building Materials

September 13, 2023Adaptive reuse project in Seattle is paving the way for the use of innovative building materials and systems that drastically cut the embodied carbon associated with construction.

Photo by Don Davies

Veteran structural engineer Don Davies has a dream. He wants to grow farm-to-building materials. Davies already owns the family farm in his native Idaho, but isn’t quite ready to plant the seeds to realize his dream. One reason is that the Seattleite is busy cultivating a broader movement: slashing embodied carbon in the built environment. And he is doing that by forgoing engineering and donning an owner’s hat.

Structural engineer Davies (left) and his wife Crooks are donning the hats of commercial developers to take action against climate change.

Photo by Clara Pathe/Dakos Photography

Davies’ debut sustainable development is a 5,126-sq-ft adaptive-reuse and seismic-retrofit project in the Green Lake section of Seattle—about a half mile from his home. In early 2021, when Davies and his wife, environmental policy activist Joan Crooks, bought the two-story unreinforced masonry building they recently named Hubbard’s Corner, they had a vision. The project would not only breathe another 100 years of life into the 1912 brick bearing-wall building, it would serve as a living laboratory to test and showcase cutting-edge low-embodied-carbon systems and materials, among them cement, concrete, steel, timber and insulation.

“I saw an opportunity to put into practice many things we talked about but never, as a structural engineer, had the opportunity to control,” says the 58-year-old Davies, who left Magnusson Klemencic Associates in February after 33 years, including his last eight as president.

The Davies-Crooks shift from the sidelines to the front lines of fighting climate change has two overarching goals—removing, for others, the fear factor from specifying the latest eco-friendly products, and creating a development model for embodied-carbon reduction.

“We are learning—gaining insights and trying to de-risk the use of these new materials and ideas,” Davies says. “Doing this with our own money, then telling that story, is leading by example and makes it easier for fast followers to act, who can scale to much larger projects.”

For more than a decade, Davies has been active as a volunteer in the green buildings community, primarily to steer the collective conversation away from operational carbon reduction only and toward embodied carbon reduction.

In doing so, he became frustrated. “The building community is spending energy on setting goals” for carbon reduction, says Davies, cofounding principal, with Crooks, of Davies-Crooks Associates. “There’s a lot of talk,” yet action is slow, he adds.

Formed this year, the fledgling Davies-Crooks concentrates on consulting and adaptive-reuse development related to lowering negative climate impacts. At the two-story Hubbard’s Corner, which is on course for completion this spring, Davies focuses on the base building and Crooks on the interiors.

Mobile batch plant, called a volumetric mixer, enabled the premiere of C-Crete Concrete for basement foundations and shear walls, cast using a portland-cement-free binder from C-Crete Technologies.

Photo (of truck) by Don Davies; other three photos: Photos Courtesy C-Crete Technologies

*Click on the photos to see more detail

As rookie commercial developers, taking on even a rather modest-in-size rehabilitation, full of unanticipated conditions so common to renovations, involves risk. It is downright daring to break new ground by experimenting with untested materials, chorus team members.

Some products, including portland-cement-free C-Crete Concrete, are making their debut at the site. “Don Davies was willing to take the risk to validate C-Crete Cement on his own project,” says Rouzbeh Savary, cofounder and president of C-Crete Technologies.

The C-Crete Concrete, supplied by Heidelberg Materials, “is the most unique material [in the building], from my perspective,” adds Martin Josund, president of the project’s general contractor Bright Street Construction Inc., which is self-performing concrete work.

C-Crete Concrete may be the most novel material, but it is not the only new product. The walls of the basement mechanical room will be made from microalgae-based ProZero Bio-Block, a low-carbon substitute for concrete block produced by start-up Prometheus Materials Inc. in its pilot plant.

And Sublime Cement, a portland-cement substitute produced using a less heat-intensive electrochemical process than a kiln, will be used for the first time both within the ProZero walls and in the exterior slab on grade and sidewalk. “Don Davies is a tremendous advocate” for sustainable building, says Leah Ellis, cofounder and CEO of the start-up, Sublime Systems.

The second floor contains the first use as shear walls of VersaWorks veneer-laminated-timber panels from Boise Cascade. And HempWool batts from Hempitecture, made of 90% natural fiber, are used in the walls and ceilings for thermal and acoustical insulation.

In a different materials-use twist, nine of the 10 tons of structural steel in the project, which includes two lines of exposed chevron braced frames on the ground floor, were selected from the steel fabricator’s “boneyard,” which contains leftovers from previous orders.

Hubbard’s Corner’ hand-picked team, by Davies, including suppliers of novel materials to create a model for reduced embodied carbon. Architect Ward (back row, second from left), structural engineer Renouard (front row, center) plan to recommend the sustainable strategies to future clients.

Photo by Clara Pathe/Dakos Photography

Davies’ Idea

The boneyard strategy was Davies’ idea. After designing the seismic retrofit structure, engineer Swenson Say Faget sent the drawings to Metals Fabrication Co., which in turn sent back an inventory list of shapes that might work, before preparing shop drawings. Then, SSF adapted the design to the inventory, where possible.

The more collaborative approach minimizes the mill order for new steel, and the inventory steel costs less, says Todd Weaver, CEO of Metals Fab. But it requires an extra step, adds Francesca Renouard, SSF’s associate principal.

Though the extra step is necessary, an inventory list at the start of design would help, Renouard says. She plans to suggest the boneyard strategy to other clients.

Happy to sell its inventory, Metals Fab plans to be more aggressive with substitutes in the future. “It was cool and went well, but it won’t work on every job,” says Weaver. “It’s harder to do on bigger jobs,” he adds.

Davies and contractor Martin Josund (right) inspect a C-Crete Concrete test cylinder. The first use of the material, made using nanotechnology, required special measures.

Photo by Clara Pathe/Dakos Photography

Hubbard’s Corner, built as an unreinforced-masonry bearing-wall building with flexible wood diaphragms, will have all the bells and whistles of sustainability, including rooftop solar panels and electric heat pumps. The trapezoidal footprint is roughly 35 ft x 77 ft. A restaurant has a 10-year lease for the ground floor. The upper level will be offices, including those of Davies-Crooks.

The mom-and-pop developers bought the building for $2.5 million. They have declined to disclose the construction cost, other than to say that the new materials haven’t changed the budget by more than 2%.

“Our biggest cost variables—and risk management—have been tied to existing-building surprises, asbestos abatement and permitting review and approval challenges, especially around utility infrastructure upgrades for electrical power and water,” Davies says.

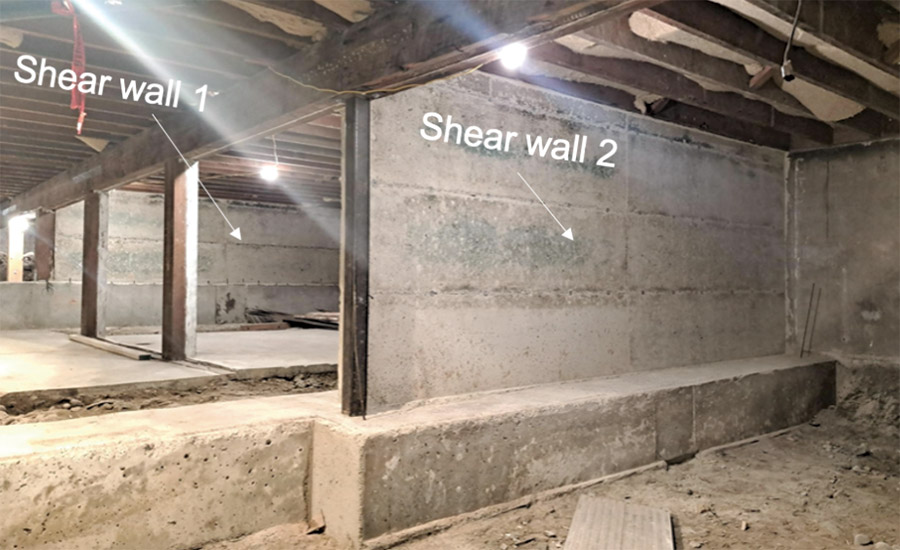

The restaurant is a change of use that triggered a full seismic retrofit. The building needed some new lateral support. The hybrid system consists of two lines of stacked structure in the short direction, from the basement to the roof. Mass timber wood panels at the upper level transfer lateral loads to the exposed-steel braced frames on the ground floor that in turn transfer loads to the basement’s reinforced concrete shear walls, each 15 ft long. Each wall bears on a 32-ft-long concrete grade beam. The beam is the full width of the basement to decrease the total amount of seismic uplift, says Renouard.

The seismic retrofit also includes parapet bracing, diaphragm strengthening, out-of-plane wall anchorage and out-of-plane wall strengthening.

Of the 10 tons of structural steel in the project, 90% was fabricated from the leftovers in the fabricator’s boneyard.

Photo courtesy Metals Fabrication

Intimately Involved

Though they hand-picked their team, Davies and Crooks stay intimately involved in design and construction. Davies even started out as the structural engineer. He says he fired himself when he failed to meet deadlines.

Mark Ward, founder of three-person Upward Architecture, says his client’s deep involvement is a partial role reversal. “It’s the most unique part of a unique project,” he says. Typically, “if a client wanted to pursue a low-carbon strategy, we would research solutions with a pros-and-cons analysis,” says Ward. “In this case, Don and Joan did the legwork.”

The building contains mass timber panels and braced frames for seismic resistance HempWool insulates the ceiling.

Photo by Don Davies

Describing the job as an ongoing full-team collaboration, Ward nevertheless calls it tricky and nonlinear. It lacks “the traditional buttoned-up plan and spec book for the contractor,” he says. That would have been more efficient but antithetical to the client’s vision, he adds.

Blazing greener trails has been educational. The biggest obstacle, especially concerning new materials, has less to do with material science and chemistry than the usual resistance to change, says Davies.

For low-carbon concrete, the complications involve a deficit of ready-mix plant infrastructure; a need for extra time for testing; and a better system for storing, shipping, mixing and placing the new materials. “That’s been a real eye opener,” Davies says.

For Crooks, the dip into development after a career as an environmental policy activist, mostly with the nonprofit Washington Conservation Action, is providing a changed outlook. “I worked on policies for so long from a theoretical perspective but now I’m wearing a different hat,” Crooks says. “I’m learning some of the obstacles to the implementation of those policies.”

HempWool is used in different thicknesses as both thermal and acoustical insulation.

Photo courtesy Hempitecture

Her biggest eye-opener on Hubbard’s Corner concerns the disconnect between well-intentioned environmental mandates—specifically for all-electric new buildings and substantial retrofits—and the inability at the local level to implement the mandate mostly because of staff shortages. The Hubbard’s Corner team applied for increased power service early in design, more than 1.5 years ago, and is still waiting for it because the electric utility is backlogged.

At the site, demolition and early asbestos abatement started in June 2022. Bright Street started work that October. Crews cast C-Crete Concrete for the foundations in May, the same month crews started installing HempWool. Crews erected the braced frames in June, followed by the mass-timber shear walls in July.

The ProZero Bio-Block and Sublime Cement work is set for next month, as is the initial handoff of the first floor restaurant to the tenant. The restaurant is set to be done in the first quarter of next year and the second floor offices in the second quarter.

Bright Street’s Josund, who has known Davies and Crooks for 30 years, calls the project “a unique challenge.” Availability and supply chain issues for some of the green materials specified forced workarounds. The first-ever use of C-Crete involved added steps. And crews had to use a circular saw rather than a utility knife or serrated blade to cut the HempWool. That added time and labor costs.

Still, Josund says he would “be happy” to construct another eco-friendly building, if given the opportunity.

C-Crete Cement

During the multiyear development of C-Crete Cement, based on nanotechnology, Rouzbeh Savary’s team tried more than 2,000 failed recipes, seeking the best way to interconnect the binder’s pozzolanic ingredients at the molecular level. “From each failure, we learned lessons and narrowed it down,” says Savary, founder and president of start-up C-Crete Technologies. He’s now seeking partners to build a plant to produce 1 million tons each year of the portland-cement-free binder—the output of a typical cement plant.

Photo courtesy C-Crete

HempWool

HempWool is a bio-based thermal batt insulation, containing 90% hemp and 10% polyester. It is a 1:1 replacement for conventional insulation and is cost competitive with rock wool. Hempitecture’s first U.S. plant, in Idaho, went online in February. The supplier is getting close to adding a bio-based fire retardant to its product line, says Jonnie Pedersen, director of communications and growth. “We have created a blueprint for manufacturing we can copy and paste in other areas that have industrial hemp growing,” she says.

Photo courtesy Hempitecture

Test Case

Davies started exploring the use of C-Crete a couple of years ago. He first asked Larry Busch, in charge of special projects in the Redmond, Wash., office of Heidelberg, about using the project as a test case for next-generation low-carbon concrete alternatives.

ProZero Bio-Block will form walls around the basement’s mechanical room.

Photo by Clara Pathe/Dakos

Independently, Davies had been working with C-Crete’s Savary on low-carbon concrete for use in the Bay Area, where C-Crete is located.

Davies soon introduced Busch to Savary, to explore the possibility of shipping the C-Crete ASTM C1157 cement binder in super sacks from the Bay Area to Seattle, to let Heidelberg experiment with the binder in its laboratory and, hopefully, for use in the project.

SSF’s Renouard was part of early discussions and helped create the design specifications. She also reviewed the lab’s test findings and agreed that the mixes would work. “After preliminary testing and favorable results from Heidelberg, we agreed it was a go,” says Davies.

Initial mix design criteria included 4,000 psi at 56 days for an interior structural application, pumpable with a 6-in. target slump.

Still, there were hurdles. The biggest one was a lack of silo space for C-Crete Cement at the local Heidelberg batch plant. Also, use of the plant for batching would have required shutting down and cleaning out the mixing hopper and then cleaning out the hopper before the plant could be used again for normal operations.

Other wrinkles had to be worked out regarding storing the binder, dry material mixing and batch control. For storage, “we used a shipping container, with super sacks of C-Crete inside,” says Davies.

To overcome the biggest hurdle, “Larry suggested renting a volumetric mixing truck as a mobile batch plant,” says Davies. That worked but was an added expense.

Volumetric mixers carry coarse aggregate, sand, water, binder and admixtures all in different containers within the truck. Ingredients are mixed on demand by a screw auger at the bottom of the truck, just before the material leaves the truck. There is no waste.

Crews cast the foundations conventionally except for the use of two 10-cu-yd mixers at the site, which delivered the batched C-Crete Concrete directly into the concrete pump truck. The basement shear walls were cast later using a volumetric mixer at Heidelberg’s plant, batching the material into a regular drum mixer driven to the site.

“That second step was added to give the C-Crete more time to wet mix and ensure good material distribution prior to placement,” says Davies. It also helped ensure batching quality control and mimicked larger volume production, he adds.

ProZero Bio-Block

Inspired by the composition of coral and seashells, Prometheus Materials’ manufacturing process combines microalgae with other natural components to form a bio-cement and bio-concrete. The startup began production at its pilot plant this spring. “We are in the process of raising a Series B round of funding,” says Loren Burnett, president, CEO and cofounder of Prometheus. Some of the proceeds will be used to build a 35,000-sq-ft precast bio-concrete products plant to produce larger quantities, he adds.

Photo courtesy International Masonry Institute

Sublime Cement

Instead of hot kilns, Sublime Systems uses a cooler-temperature electrochemical process to produce a very low-carbon replacement for portland cement. A pilot plant, with an eventual capacity of 250 tons per year, has produced 10 tons. The goal is to have a facility operating by the end of 2025 that can produce 30,000 tons per year, says Leah Ellis, cofounder and CEO of Sublime Systems. As with any binder, the ready-mix producer would need a separate storage silo for large-scale production of concrete using Sublime Cement, she says.

Photo courtesy Nathan Eisenberg/ Sublime Systems

The concrete flowed well from the pump truck, was cured following normal construction procedures and included wet blanket curing of horizontal surfaces, says Davies.

Terracon/Mayes Testing provided independent laboratory evaluations of the C-Crete Concrete. Extra cylinders were taken to collect strength-gain data for up to 180 days. Temperature and maturity meters were used to track the in-place mix performance.

The city also had to review and approve the mixes. Key to that was that the C-Crete had been precertified to meet ASTM C1157 criteria; mix data included cylinder break figures; and the mix, preapproved by the engineer of record, met American Concrete Institute requirements.

Average break data on the walls was in the range of 2,400 psi at three days and 6,000 psi at 56 days, well above the initial 4,000 psi target, says Davies.

Remaining concrete work will include variations of the mix, applied both to the interior and exterior slabs on grade. “We will also pour a 7,000 psi mix to see what is possible, even through the project won’t require more than the initial 4,000 psi concrete,” adds Davies.

Sublime Cement’s pilot plant went into limited production just this year. To date, it has produced about 10 tons.

Photo by Nathan Eisenberg/Sublime Systems

Though C-Crete and the project team consider the use of the concrete a success, Heidelberg, which produces portland cement and ready-mixed concrete, is not yet talking about the C-Crete binder’s future in its product line.

“As with all innovative product development we undertake, we work carefully to ensure diligence in evaluating all data before reporting on findings and identifying next steps,” says David Perkins, Heidelberg’s vice president of government affairs and corporate communications for North America. He anticipates the data won’t be available for review and analysis for several months.

Though measurement of the embodied carbon reduction in the redevelopment is incomplete, there are good preliminary numbers, says Davies. “We are conservatively tracking over 75% below a ‘business as usual’ embodied carbon baseline that uses project-specific quantities and industry median data,” as taken from the Carbon Leadership Forum 2021 Materials Baseline Report and Industry Average Environmental Product Declarations within the Embodied Carbon in Construction Calculator, he reports.

But he cautions: “Even with carbon neutral and potentially carbon negative materials, the project will not achieve an embodied carbon negative footprint when construction is complete.” For instance, there is no carbon negative plumbing. “To quote our plumber at the end of a meeting: ‘There aren’t environmentally friendly plumbing materials today,’” says Davies.

“Zero is hard,” he adds. “It is an aspiration, but as an industry we are not yet creating true net-zero embodied carbon construction, if we are real with the numbers.

“This project will prove that out,” says Davies, who plans to share all the data with developers and their building teams, in the hope that others will follow his lead into lower-carbon construction.