All robots, as well as the paint shop and other equipment in automaker Rivian’s Normal, Ill., production facility were designed by its in-house team, which also did design of parts for its R1S and R1T electric vehicles.

Photo courtesy of Rivian

The Biden administration’s Federal Sustainability Plan, announced in April, will require all federal agencies to transition to light-duty electric vehicles by 2027 and heavy-duty zero-emission vehicles by 2035.

To meet this challenge and the broader transition to electric vehicles, contractors, EV manufacturers, development consultants and transportation designers and planners have had to shift their methods to speed up design and construction and better predict the needs of the still-growing market while also identifying the best locations for everything from charging infrastructure to new factories.

Infrastructure designers and contractors say they have not seen a shift in transportation this big since the automobile replaced horses and carriages in the 1920s.

The U.S. Dept. of Transportation has said in a statement that it is working with states and local governments to build a national network of 500,000 publicly accessible EV charging stations by 2030. The Federal Highway Administration noted in a press statement that 160,000 public EV chargers are active across the U.S. today, but at the end of 2022 only 28,000 were direct current, fast-charging, Type 2 ports versus slower Type 1 ports. For comparison, there are around 145,000 gasoline stations in the nation. Some $2 billion from the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act has been committed to backing production facilities for new EVs.

Just this month, automakers such as Hyundai and Ford announced they are offering cash rebates as high as $7,500 per vehicle to combat slumping EV sales. Despite this, the industry is planning for long-term growth.

Automakers Ford, General Motors and Rivian all agreed this year to make their EVs capable of using the North American Charging Standard (NACS) ports, which is based on charger hardware that automaker Tesla has been using thus far. Tesla has the largest built-out charging network in the U.S. today, and there were signs that automakers might end up with competing charging networks. Tesla has agreed to open a portion of its network to charging other vehicles, and wider adoption of the NACS standard is part of that effort.

Federal programs aim to create national corridors of EV chargers.

Photo courtesy of HDR

EPC Work Just Like Designing an EV

When Tesla built its first gigafactory in 2014—a lithium-ion battery, EV drivetrain and other electric vehicle component manufacturing facility near Reno, Nev.—the automaker essentially became its own engineer-procure-construct contractor. At 5.4-million sq ft, the facility required a unified approach. Tesla also wanted design and construction to be performed closely together, because that’s how they create their vehicles.

“We had an engineering group and an EPC team.”

John Vardaman, Former Tesla Construction Manager, Advanced Tech Core Market Lead: Advanced Manufacturing, DPR Construction

“It started with the company philosophy to in-house a lot of the expertise and the decision making, the planning and execution of everything from how the car and the parts of it were being designed and built and extend that into construction,” says John Vardaman, who was director of construction management at Tesla at the time before returning to DPR Construction in 2017. “They saw that [approach] as an integral piece of how they wanted to deliver the Model 3, which was what we were ramping up to. We in-housed our own general contractor and procurement group. We had an engineering group and an EPC team.”

Given the scale of the gigafactory, Vardaman found it was more useful to break the work down for individual EPC teams that could coordinate among themselves. He brought this philosophy back to DPR and has applied it to other complex, mission-critical projects of a similar scale, such as data centers.

“It was up to us [as the management team] to coordinate those efforts, like any EPC firm,” he explains. “That gave us options.”

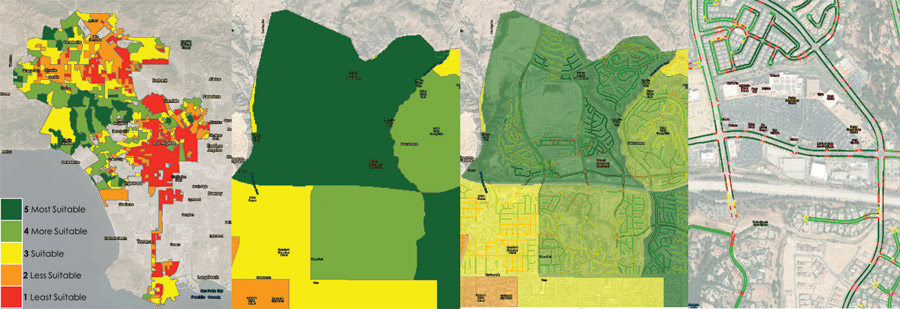

An ArcGIS map compares charging station locations in Los Angeles. When compared against residents’ income data, it shows a lack of investment in underprivileged communities.

Map courtesy of Arup/charge4all

Vardaman acknowledges that as owner and EPC contractor, it meant Tesla owned that risk, but it got the project done on time and within its $6.2-billion budget. He said that at the peak of gigafactory construction, the facility workforce doubled the population of Storey County, Nev., where it was located. The in-house EPC approach got the most out of the construction schedule, while also allowing Tesla to plan for production at the same time. Despite construction challenges, the focus had to be on what was coming into the building, how tooling would be integrated and how production machinery would achieve peak efficiency.

Rivian took a similar approach when building out its Normal, Ill., production facility, which it converted from a former Mitsubishi factory for a reported cost of $750 million. It is using the same approach for a new facility in Georgia.

“You’re working very closely with supply chain, manufacturing, engineering. They will tell you how much space they need for all the stations, how you want the flow of a production line running, where do we want inventory, so there’s a lot of planning that goes into that,” says Jeff Hammoud, Rivian chief design officer. He adds that Rivian’s team does a lot of design work for a facility in house before bringing in architects and engineers to create drawings and work out fine details. This iterative process for facility design is similar to the one Rivian uses to develop parts for its electric vehicles.

Using nine different machined components, this prototype Rivian subframe was designed with the same approach the that the automaker's in-house design team brings to its facilities and charging stations.

Photo by Jeff Yoders/ENR

Building Out a Network

Like Tesla, Rivian is also opening up its charger network to work with EVs from other manufacturers, and there are other recent shifts driving the construction of charging infrastructure.

The Inflation Reduction Act includes a provision for businesses that install EV charging equipment to receive a federal tax incentive of up to 30% of the total cost of equipment and installation. Developers can achieve a tax credit of up to $100,000 for installing charging equipment in their project.

Jose Morales, vice president of construction at Austin, Texas-based mobility consultant Flash says building owners are finding themselves gently pressed to put in charging equipment. “It’s really the municipalities and the states that are saying, this is how many of those [parking] spaces have to be EV,” he says. The return on investment for EV charging ultimately depends on the network of users that come to use it.

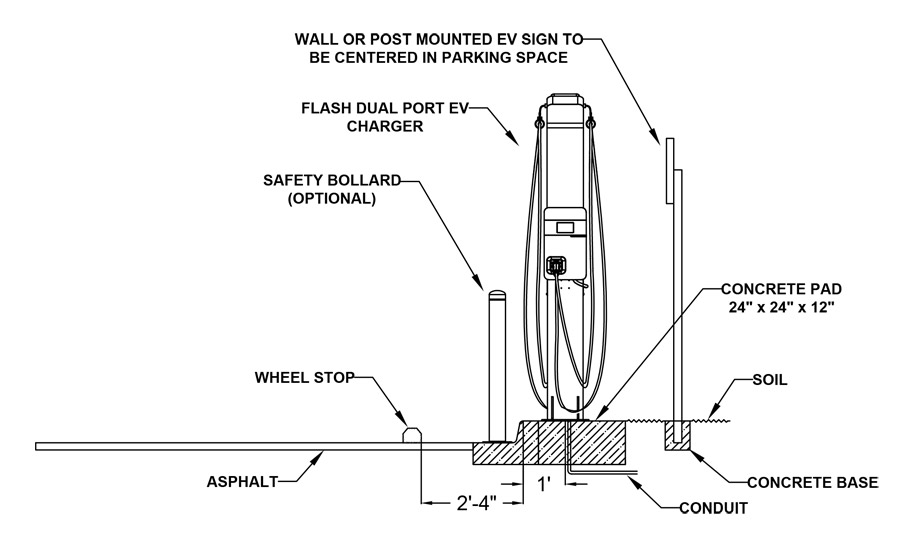

Morales recommends that developers and owners out to convert existing parking for EV charging ensure they are wired for internet connectivity and fast charging, and consider implementing a reservation system.

In building a 32-acre waterfront development in Vancouver, Wash., Gramor Development had to meet a state requirement that 10% of all parking spaces be infrastructure-ready for EVs, says Matt Grady, vice president and director of development. “We went to great lengths to see where to cluster them so that cabling can work for all the conduits.”

Vehicle charging infrastructure should include a direct current electrical supply as well as 8-gauge wire to support a 240-V circuit.

Schematic courtesy of Flash

A new parking garage will have 10 Type 2, 19 kWh chargers. “They will be mounted onto columns next to the parking spaces. Future conduits are stubbed up on each floor above to accommodate [future] demand. There’s space in the electrical room for more panels to be installed.” Looking forward, Gramor President Barry Cain notes that “the machines we’re looking to use now weren’t available two years ago. Who knows what will come in the next few years?”

Arup Senior Geospatial Analyst Samantha Lustado, based in Los Angeles, has worked with California utility providers and the Los Angeles Cleantech Incubator to create a web-based, site-suitability tool for EV charging stations called Charge4All. Using GIS technology, Charge4All analyzes data on transportation and energy networks, demographics and EV adoption to identify areas within Los Angeles where EV chargers will be needed as adoption increases. Arup worked with Burbank Water and Power, Los Angeles Water & Power, Southern California Edison, as well as City of Los Angeles departments and other stakeholders to develop the tool.

“We’re trying to

forecast power demands for medium and heavy duty vehicles.”

Rob Mowat, Transportation Electrified Mobility Lead, HDR

California, Oregon and Washington are planning a 1,400-mile EV corridor along Interstate 5 between Canada and Mexico, with 34 stations and five hydrogen fuel stations planned, says Jimmy O’Dea, assistant deputy director for transportation electrification at the California Dept. of Transportation. The agency is partnering with the state energy commission and its DOT counterparts and hopes for federal funding by year’s end, he says. States and agencies bid for $700 million worth of such funding earlier this year.

“We submitted a statewide proposal, and are also supporting 20-plus projects for charging in local districts,” says O’Dea. “The projects range in scope and scale. For some projects, it may be easier to install chargers at a site if the power is available and it doesn’t need upgrades. For many others, like truck charging stations, fairly high power is needed and likely will require upgrades on electrical infrastructure.”

He notes that the challenges associated with ramping up EV infrastructure include contractors having enough staff to design and install it.

“It’s a good time to be an electrician,” he says.

O’Dea adds that standards are being finalized and are in the proposal for the West Coast Truck Clean Transit Corridor Initiative. If successful, the effort will require each site funded to future-proof for a higher power level. The fastest is 350 kW today but development of megawatt-speed charging is expected in the future. Most charging stations today do not require the footprint of a gasoline service station and may never need one. The transition still offers design opportunities to define what a charging station has to look like. “We are looking at how can we bring in zero-emission infrastructure projects into all aspects of our work,” says O’Dea.

Power Plays

Transportation engineering firms that typically work on infrastructure such as highways and bridges are finding work in the EV space.

HDR is leading a study for the West Coast Clean Transit Corridor initiative that involves Caltrans, and is working with states vying for funds from the National Electric Vehicle Infrastructure Program (NEVI), which will provide nearly $5 billion through 2027. Rob Mowat, HDR's transportation electrified mobility practices leader, says a partnership between the California Energy Commission and Caltrans is one of the first implementations of the federal NEVI formula program that aims to create a nationwide, interconnected network of 500,000 direct-current fast chargers along the U.S. highway system.

“We’re trying to forecast power demands for medium and heavy-duty vehicles,” he says. Noting the increased energy needs for heavy-duty vehicles, Mowat explains that “600 kilowatts—that’s nothing. Truck stops need 15 megawatts. Where will it come from? Where do you put all these trucks as they sit for 30 to 40 minutes? Coordination between utilities, regulatory boards and policymakers will be important.”

Andrew Conley, HNTB project director, notes that with the introduction of NEVI in the 2021 Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, “MPOs, counties, cities, transit agencies, and airports are all either planning or deploying EV infrastructure.” The firm is working with 13 states on projects to implement NEVI.

“Broadly speaking, what’s unique about NEVI is its formula funding to deploy fast-charging stations every 50 miles along the Interstates and within 1 mile of exit ramps," he says. "The fuel corridors are designated by FHWA. It’s a pretty clear set of parameters and assignments. The first flush [of funds] is dedicated to long-distance travel before going on to local deployments.”

Experts expect an increase in overall demand on the grid as adoption of electric vehicles grows and charging equipment continues to evolve.

Photo by Justin Sullivan/Getty Images

It’s a brave new world for DOTs, says Conley. “Obviously many DOTs have not done much with EV charging, just like they don’t fund gas stations. They weren’t typically in that business.”

Challenges include the rural areas along the Interstate system where “in the near term it’s not the most optimal location,” he says. Even Rivian’s initiative to install chargers in state parks have the infrastructure for visitors centers and park buildings to work with.

Conley also notes that there are complexities in making sure entities are fulfilling the “unique” categories of NEVI. “Typically this bridge or that road segment—it doesn’t generate revenue. With NEVI, because chargers must be within a mile of highway ramps, it’s not DOT property,” he explains.

There will also be opportunities for creative P3s while adhering to legal requirements for a DOT to own and operate the asset. “The real challenge is how fast the technology is evolving. In 2018, a fast charger was 50 kilowatts per hour. NEVI requires 150 kilowatts. Some states have proposals for 350 kilowatts, 400 kilowatts,” he says. NEVI sites will require four spaces, each with a 150 kWh charger. If all four are being used at once, that’s 600 kW in one hour. “There has to be coordination with utilities and local transformer upgrades that [will] need to take place.”

Conley adds that there is still uncertainty around plug and connector technology, even as most automakers have agreed to NACS. He said it’s still possible that both NACS and the Combined Charging System—the de facto standard in Europe and still favored by automakers like Volkswagen—will have to be baked into procurement specifications someday.

There is consensus, however, on the need for broader collaboration, including first responders and towing companies. “For all stakeholders, there’s something unique that may affect them,” says HDR’s Mowat.