Award of Excellence Winner Kit Miyamoto Travels the Globe to Help Countries Rebuild From Disaster

April 11, 2024

Award of Excellence Winner Kit Miyamoto Travels the Globe to Help Countries Rebuild From Disaster

April 11, 2024Kit Miyamoto says he will not let employees travel to dangerous locations, such as Ukraine, without being willing to put his own life at risk.

Photo By Yuri Stefanyak/Courtesy of Miyamoto International

Related Link:

ENR 2023 Top 25 Newsmakers

On May 12, 2008, a devastating 7.9-magnitude earthquake in the Sichuan province of China caused nearly 90,000 people to lose their lives, with hospitals and schools filled with children disproportionately affected, even as buildings around them remained unscathed. Government officials said more than 5,000 children died, with another 500 left permanently disabled.

State officials initially acknowledged that shoddy construction and corruption during China’s economic boom were at least partially to blame. But The New York Times reported one year later that the Chinese government was walking back those statements and taking measures to silence parents and advocates demanding answers on why so many school buildings collapsed.

China also limited the entry of international engineers to assess the damage immediately following the quake, although at least one team from Europe was able to perform damage assessments in an official capacity.

Miyamoto in Morocco following September 2023 earthquake (top); in Ukraine with the Miyamoto Ukraine team (bottom, right); and meeting with dignitaries in Nepal in 2018.

Photos courtesy of Miyamoto International

Meanwhile, one intrepid American engineer was so distressed by the event that he didn’t wait to be called—packing his bags and entering the authoritarian nation on a tourist visa. “In my mind, I just wanted to see what really happened, to see why all those people died there,” says Kit Miyamoto, CEO and humanitarian coordinator of Miyamoto International, a disaster recovery and structural engineering firm based in Sacramento, Calif.

While the majority of commercial buildings suffered little damage from the quake, in many of the schools, not a single child survived. What confounded Miyamoto was that “there was no need for it to be that way at all,” he says, shaking his head. The engineer was among a small group of global experts who wrote technical papers identifying reasons for the collapse of most of the schools and other structures—largely concentrated in rural communities—which were built with very little seismic resistance or redundancy, and which used unreinforced brick walls and other sub-optimal structural configurations.

Miyamoto’s technical investigative report, published in 2008, was subsequently translated into Mandarin and helped inform the body of knowledge that led to a 2011 upgrade to the country’s building codes related to seismic design, and a national strategy for disaster risk reduction that foregrounded school safety.

The trip proved transformational for Miyamoto, both personally and for his privately held company. Although the firm had begun to foray into international disaster and recovery contracting in the early 2000s, seeing so many children die unnecessarily was a wake-up call that amplified the critical need for more global education and information sharing, he said.

Over the years, the engineer has responded to impacts of earthquakes, climate disasters and international conflicts in countries as diverse and challenging as Turkey, Ukraine, Morocco and Haiti. In addition, Miyamoto founded the nonprofit Miyamoto Global Disaster Relief to develop and implement more enduring best practices and use of technology.

For his tireless drive in working with communities to rebuild after calamities and engineer enduring solutions for a disaster-plagued world through technical innovation and seismic design information exchange, ENR’s editorial team has selected Kit Miyamoto to receive its 59th Award of Excellence.

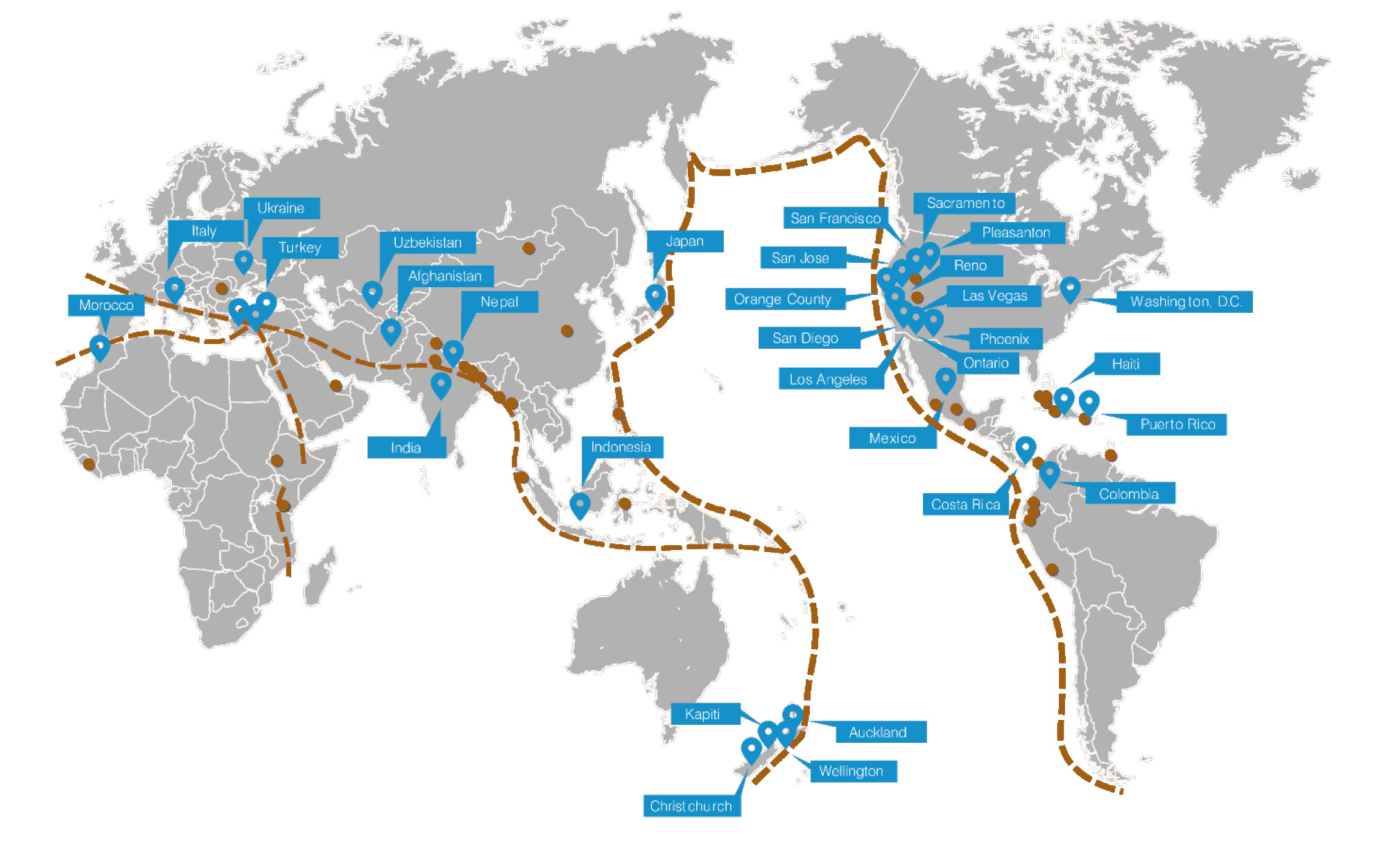

Although the decision to add “International” to the company’s name was largely aspirational at first, the firm has steadily grown from the original office in Sacramento to locations in 19 countries.

Left to right: A team of California Polytechnic students on a Miyamoto-led tour in Nepal; Miyamoto in China after 2008 earthquake; and a child being led by a Miyamoto employee in quake-damaged Haiti.

Photos courtesy of Miyamoto International

Left to right: Miyamoto with locals in Afghanistan; with Pavlo Pokhalchuk, Miyamoto Ukraine CEO; and appearing on CNN, where he has been a frequent expert commentator.

Photo right, courtesy of CNN; Others courtesy of Miyamoto International

Left to right: Miyamoto’s Haiti team has gained locals’ trust; the firm is rebuilding structures damaged in a 2020 earthquake in Puerto Rico; a building under repair in New Zealand.

Photos courtesy of Miyamoto International

Bucking the Status Quo

Miyamoto has always been a bit of a maverick. Mark Zweig, founder and former CEO of AE management consultant Zweig White, describes him as “pretty much a nonconformist in every way.” A board member of Miyamoto Relief, Zweig says that the activist engineer is “extremely creative and very brave. He doesn’t mind putting his life in danger, every day if need be, and he’s one of the hardest-working people I’ve ever known.”

Miyamoto is known for his early advocacy in use of fluid viscous dampers when feasible, here in first U.S. application in 1995 at Hotel Woodland in California.

Photo courtesy of Miyamoto International

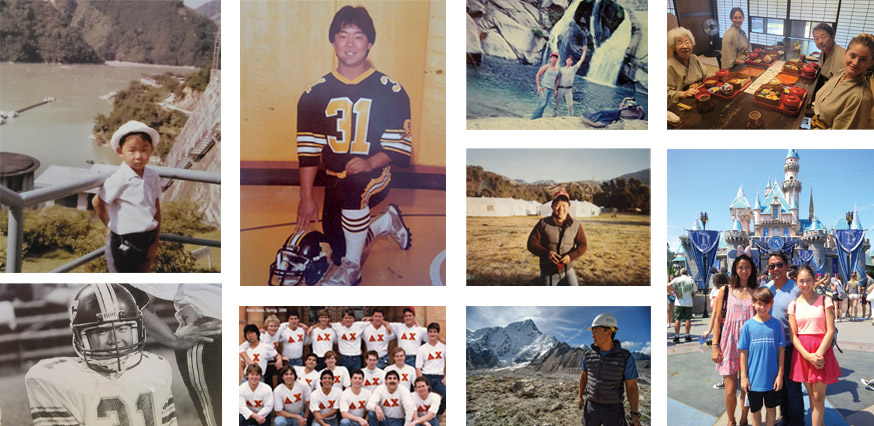

Miyamoto says that although he appreciated aspects of his early life growing up in Japan, its social constraints felt restrictive. “It was a very difficult place to innovate or do different things,” he says. A high school graduation picture shows him in a golf shirt, among a sea of his peers wearing suits. He informed his parents he wanted to come to the U.S. to play professional football for the Dallas Cowboys. In 1982, Miyamoto moved to the states and did play football at Butte College for a short time until a knee injury waylaid his dreams of an athletic career. So he moved on to Plan B: a career in structural engineering.

After earning a civil engineering degree from California State University, Chico, he joined Sacramento-based structural engineering firm Marr Shaffer in 1989. Miyamoto quickly rose through the ranks, eventually purchasing the firm when owner John Shaffer, one of his first professional mentors, retired in 1997. The company was rebranded Marr Shaffer & Miyamoto. He later earned a doctorate in structural engineering at Tokyo Institute of Technology.

The company quickly expanded beyond Sacramento through the early 2000s as Miyamoto developed a reputation for innovation on structural engineering projects—notably advocating for use of fluid viscous dampers and performance-based engineering before they were commonly considered in risk mitigation projects.

The firm has worked on some of the most iconic buildings in Los Angeles since then, performing seismic risk-reduction retrofits and structural design at sites that include the Griffith Observatory, Los Angeles International Airport, Universal Studios and the Hollywood Bowl.

John Hooper, senior principal and director of earthquake engineering at Seattle-based Magnusson Klemencic Associates, recalls working with Miyamoto in the early 2000s on a peer review panel for a seismic upgrade to the King County, Wash., courthouse, which used dampers as a key component. Although he has watched Miyamoto’s career trajectory from afar, Hooper says he appreciates the engineer’s consistent approach in pushing for the most effective project solutions.

“It’s very helpful to the structural engineering community to have someone who’s willing and able to really send the message about what is being done and what should be done to help make not only the United States safer, but also countries that are earthquake-prone,” says Hooper. “Kit is a very good spokesperson for that.”

Former California Gov. Jerry Brown (D) in 2011 appointed Miyamoto as a commissioner on the state Seismic Safety Commission, a position he still holds. Richard McCarthy, commission executive director for nearly 30 years until his retirement in 2022, says Miyamoto has not only brought strong technical expertise, but also real-world experience to know which strategies really work and which do not. “He embeds [into] these disaster areas,” McCarthy says. “Kit is a very unique individual with unique experience.”

James Mwangi, associate dean of the College of Architecture and Environmental Design at California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo, has moved in similar professional circles as Miyamoto since 1994, when both worked for different structural engineers in Sacramento. “Kit is very well-respected in the structural engineering community in California,” he says. “We were not surprised when he was appointed” to the state seismic safety commission.

Miyamoto Relief successfully advocated for funds to repair the neoclassical Gaddi Baithak building in Nepal that officials had planned to demolish.

Photos courtesy of Miyamoto International

Going Global

In the early 2000s, Miyamoto added “International” to his firm’s name. At the time, the change was mostly aspirational. “We wanted to share our knowledge and experience not only with California but also on a global scale because there are just so many places affected by earthquakes and disasters,” he says. But with the firm still in one small office in Sacramento, “People just thought that was crazy,” he says with a laugh.

Miyamoto reached out to professional contacts who could help realize his vision to be on the firm’s board of directors, which serves more as a backstop and advisory panel than a governing body, according to current member Jamie Claire Kiser, now a principal at Bernhard Capital Partners and former principal at Zweig Group, where she managed mergers and acquisitions.

An early board member and mentor was Peter Yanev, founder of EQE, one of the world’s largest international risk management firms. It was sold to international consultant ABS Group in 2000 before he joined the World Bank as a senior technical consultant on earthquake issues. Through Yanev, Miyamoto gained contacts for entrée to the global market. Connection to bank experts in Washington, D.C., “changed everything about what we do today,” Miyamoto says.

Yanev says he was interested in working with Miyamoto because of his willingness to take a fresh approach to engineering challenges. “The thing I liked in dealing with him and his organization was that they were very willing to take on new ideas,” Yanev says. “To me, he’s an unusual engineer in that he’s not only applying engineering concepts, but also willing to test new areas and bring life experience to his work." Miyamoto also possesses strong business acumen, Yanev adds, apparent even when they first began working together.

One of the firm’s first major international contracts was a 2008 seismic risk reduction school retrofit project in Istanbul, Turkey financed by the World Bank—a component of an ongoing seismic risk mitigation and emergency preparedness program between 2005 and 2011 that ultimately attracted more than $2.2 billion in funds.

As of 2021, the program had retrofitted more than 1,000 of the city's most vulnerable schools and hospital buildings. A 2022 World Bank economic analysis of its impact estimated damage risk to be reduced by 35% and at least 3,000 lives saved in the event of a future earthquake.

Miyamoto also cultivated the support of Zweig-White’s Zweig. “Mark is really the one who set up the foundation of the business management systems in the company,” says Miyamoto. The engineering firm now is valued at more than $30 million and generated $35 million in 2023 revenue—with more than 400 employees in 19 global offices.

Rebuilding as Missiles Fire

The firm’s Ukraine team has supervised the repair of schools damaged by Russian military fire, estimating that the cost for repairs could exceed $100 million.

Photos courtesy of Miyamoto International

Miyamoto International’s Ukraine team isn’t waiting for Russia’s two-year onslaught of the country to end before rebuilding structures leveled by missiles.

Kit Miyamoto, company global CEO, says that although the war is not over, people need homes and schools now, not at some unknown future date. He says it is easier to repair a building with partial damage caused by a missile than rebuilding a completely destroyed structure. Miyamoto has visited Ukraine multiple times, most recently in February.

The firm’s Ukraine office in Kiev has grown to more than 100 employees over the past year, led by Miyamoto Ukraine CEO Pavlo Pokhalchuk. The company has worked with the United Nations and other partners to provide design documentation and construction supervision services for damaged schools. Currently, about 56 schools are being rebuilt under supervision of the firm’s experts.

Miyamoto Ukraine also has been involved with reconstruction, renovation and upgrades of 7,500 residences, both detached single-family homes and multi-unit dwellings. According to Pokhalchuk, Miyamoto staff are typically welcomed by residents wherever they go. “When our experts turn up, many people approach us asking for help in rebuilding or renovating their homes,” he says.

Although Miyamoto engineers can’t always help, “We let them know about our current repair and construction programs, and advise them who to approach and what donor projects can offer support,” Pokhalchuk adds.

Based on what firm experts have seen in the field, it Ukraine team has developed a database of more than 300,000 damaged structures to be shared with organizations and entities able to fund the renovations.

“I think the most urgent task today is to reconstruct existing shelters and build new ones. This is about people’s lives, health and safety,” Pokhalchuk says. As his interview with ENR took place late on March 21, he says Kiev was being besieged by another massive Russian missile attack, with 31 missiles shot down by Ukraine army air defense systems that evening.

—Pam McFarland

In It for the Long Haul

Over the past decade, Miyamoto has worked down to a science his approach to countries in need of assistance. He typically builds relationships with local officials and agencies after a disaster event, as well as with people most affected by it—those who have lost their homes and way of life.

In the past year alone, he has traveled to Ukraine, Japan, Haiti and also Morocco, which was decimated by a 6.9-magnitude earthquake last September.

But once immediate assessments are done, the firm maintains a presence—sometimes teaming with local engineering and construction firms, and sometimes staffing a satellite office—to do the work of rebuilding schools, homes and hospitals.

Following the February 2023 earthquakes along the fault line intersecting Turkey and Syria, Miyamoto formed a joint venture with Protek, a small Turkish engineer, to oversee building assessment and rebuilding efforts there. A satellite office in Ukraine added 100 employees over the past year to manage recovery assistance from structural and infrastructure damage as the country continues to defend itself from Russian missiles (see story, above).

“Kit is well trusted—not just respected, but trusted—by political leaders around the world and in California,” says former state seismic safety executive McCarthy, who credits Miyamoto’s effectiveness partially to his ability to interact with people of all types and provide “no-nonsense” answers. Officials also know he’s in the recovery response for the long haul. “He always comes back,” McCarthy says.

Miyomoto also is known for his sensitive, human approach in difficult situations. “He’s really good with people … and being able to connect with them,” says daughter Mimi Miyamoto, a Los Angeles-based videographer who has traveled with him to document disaster impacts and responses for the firm.

A Change Agent in Haiti

Miyamoto establishes a long-term presence in countries affected by natural disasters and violence. The company has had an office in Haiti since a 2010 earthquake wrecked buildings in some of its poorest communities.

Photo courtesy of Miyamoto International

Miyamoto International has had a presence in Haiti—which company CEO Kit Miyamoto describes as his “third” home, after Japan and California—since 2010, when a 7.0-magnitude earthquake struck near the nation’s capital, Port-au-Prince.

One of the first people Miyamoto met there was Guilaine Victor, a Haitian with a background in business and many local connections. She began to work for him and the firm, becoming Miyamoto International’s Haiti country lead. The firm successfully gained the trust of local authorities—where other responders did not—largely because company employees did not swoop in from abroad to “save” people, she says. Instead, they offered expertise where support was needed, giving lessons in how to build in a structurally sound way. Miyamoto assessed 400,000 buildings following the 2010 quake.

The Miyamoto team also worked in some of the most impoverished neighborhoods Victor had ever encountered. About 400,000 people live in one—the 5-sq-km Cité Soleil in Port-au-Prince. While assessing structures, Miyamoto’s leadership team realized that funding was virtually non-existent for schools that did not actually collapse but were at risk. As a result, the nonprofit Miyamoto Global Disaster Relief was established.

Since 2010, Miyamoto International has rebuilt more than 100 schools, trained more than 7,000 masons and assisted 30,000 homeowners. After a 7.2-magnitude temblor in 2021, company engineers assessed another 180,000 buildings and trained additional masons and carpenters. The firm also educated 60 municipal and ministry engineers on use of better building materials and in construction and design practices that will result in functionally sound buildings, from homes and schools to hospitals.

According to Victor, the firm trains locals so they will share expertise with others—and she has seen that happen. “I can see the change, I can hear people talking and doing things differently,” she says.

—Pam McFarland

Expanding Access

Despite the company’s early global expansion that included satellite offices in Japan, Turkey and other locations, it was the trip to China in 2008 that convinced Miyamoto to think bigger.

Sabine Kast, a senior principal at Miyamoto International and executive director of Miyamoto Relief, says the company has found—through its involvement in local communities over the years—that efforts to move projects to actual construction were often stymied by lack of funding, particularly in the most economically disadvantaged parts of the world. These include areas deemed “Red Zones” because of violence or accessibility challenges that kept even humanitarian workers away, despite urgent needs, she says.

Kast says these include places like Cité Soleil in the Haitian capital of Port-au-Prince (see story, above)—where few non-governmental organizations, international relief agencies or companies venture. Often with little political clout to gain critically needed help, such impoverished and poorly built areas are further marginalized.

Local officials and responders “don’t send in their humanitarian workers because of the severe security situations,” she says. “They select other neighborhoods that have easier access,” needing “to make sure their operations and those dollars are as safely programmed out as possible.”

Through close involvement with communities where they are embedded, Miyamoto International employees have learned about such places that need help but whose residents feel largely overlooked, or worse, abandoned. Even when help does arrive, communities often distrust the motives behind it. Miyamoto is able to overcome that mistrust by getting to know locals and earn their respect without condescension, Kast says. This occurred after a 7.0-magnitude quake hit Haiti in 2010, and local teams had to assess the condition of 400,000 properties, according to Guilaine Victor, the firm’s country lead.

Miyamoto leadership began a series of internal discussions about developing a vehicle to bridge funding gaps in some of the most marginalized communities. Those led to the creation of the firm’s nonprofit arm in 2011 to access funding that was unavailable to the company as a private business, and provided needed support to communities that had few or no alternatives, Miyamoto says.

Although a separate entity, the nonprofit works hand-in-hand with the engineering firm. The latter covers the relief organization’s overhead costs, enabling the nonprofit to use all monies raised—$1.15 million in 2023—to directly fund programmatic goals that have included rebuilding schools in Puerto Rico as well as historical and cultural preservation in Afghanistan and Nepal.

From left, clockwise: Miyamoto in Japan as a child; in college football uniform; gold mining while a student at California State University, Chico; with Sabine Kast and his mother plus daughter Mimi; with his children Julia, Alex and Mimi in Disneyland; in the Himalayas; in college with his fraternity; playing football; and center, on his first earthquake reconaissance visit in Northridge, Calif. in 1994.

Photos Courtesy of Kit Miyamoto

Preparing the Next Generation

Deepansh Kathuria, a Miyamoto International principal who primarily works in California, says he has applied field lessons learned worldwide to local design projects, many in the Los Angeles metropolitan area. At the same time, Miyamoto International team members spend a lot of time and energy to educate communities in other countries about international engineering and construction best practices.

That also applies to the next generation. Since 2011, Miyamoto International has taken teams of students from Cal Poly's Structural Engineering Students for Humanity program to countries such as Ecuador, Nepal and Indonesia to support their professional development with real-world experience. One student veteran of two trips, university senior Hayle Jones, says the travel affirmed her desire to continue working in some way on projects that address community needs.

Miyamoto’s son, Alex, a freshman studying civil engineering at Arizona State University, is following in his father’s footsteps because he says he also would like to work in the engineering disaster prevention and response arena. “My dad is always talking about following your passion … what I figured out was that I’m passionate about people, and I really like STEM, math, physics, all that.”

As company teams travel the globe, Kit Miyamoto says he hopes to achieve cross-pollination of best practices built both on the latest technical expertise of the engineering community and on knowledge and experience of local communities in response to natural and human-caused disasters.

At the COP28 global climate change conference in Dubai last year, he pledged, along with corporations such as Xylem, Aon, Arup, IBM and others, to invest in climate adaptation efforts as part of private-sector engagement with President Joe Biden’s Emergency Plan for Adaptation and Resilience. Miyamoto says he would like to help establish a global coalition of experts to build a shared body of knowledge about best preventive and response practices that respect local knowledge and building techniques.

Miyamoto, pictured in Morocco, has become known for his expertise in assessing the reasons behind building collapses during earthquakes.

Photo courtesy of Miyamoto International

Mission-oriented Philosophy

Miyamoto says daily meditation—and surfing—help him cope with the stresses of running a company whose employees and chief executive venture into some of the planet’s most dangerous places. “As CEO, I’ve got to walk my talk,” he says. But Miyamoto fervently supports his company’s mission, crafted around the time he took control, to make the world a better and safer place.

Miyamoto’s focus has drawn kindred spirits into his orbit. Traci Petcoff Wong, Miyamoto International principal for Orange County, Calif., took a pay cut and a lower level position to work at the firm. Principal Kathuria joined in 2006 when he heard it not only was involved in exciting projects, but also that its approach used “common sense and not just follow-up prescriptive code,” he says. "It has held true to what it was known for.”

Haiti lead Victor recounts the day she asked Miyamoto to consider reducing her team’s paychecks because operations in the country were hurting the company’s bottom line. He nixed the idea and told her to keep going. “He loves what he does and how important it is for him [to help people] have safer places and better lives,” she says. “This is what makes me stay with Miyamoto International.” Adds Cal Poly’s Mwangi: “He’s really out there doing this not because he wants to get rich. He’s doing this for the safety of the communities, here in California and across the world. That’s who he is.”

Among peers, colleagues and friends, Miyamoto is viewed as someone who works hard, plays hard, cares deeply about his fellow humans, and most importantly, is intent on doing what he can to reduce human suffering. He says his firm is committed to those principles, regardless of politics, level of corruption or violence in the countries its employees work in. Miyamoto insists that engineers are uniquely qualified to help suffering people in an apolitical way.

“That’s why I think we can do a lot, right?. Because we can be really neutral," he says. "It’s about physics, and how to fix things.”