Sustainability

PAE Living Building Team Shares Lessons Learned

Portland, Ore., office building stands as global model for commercial Living Buildings

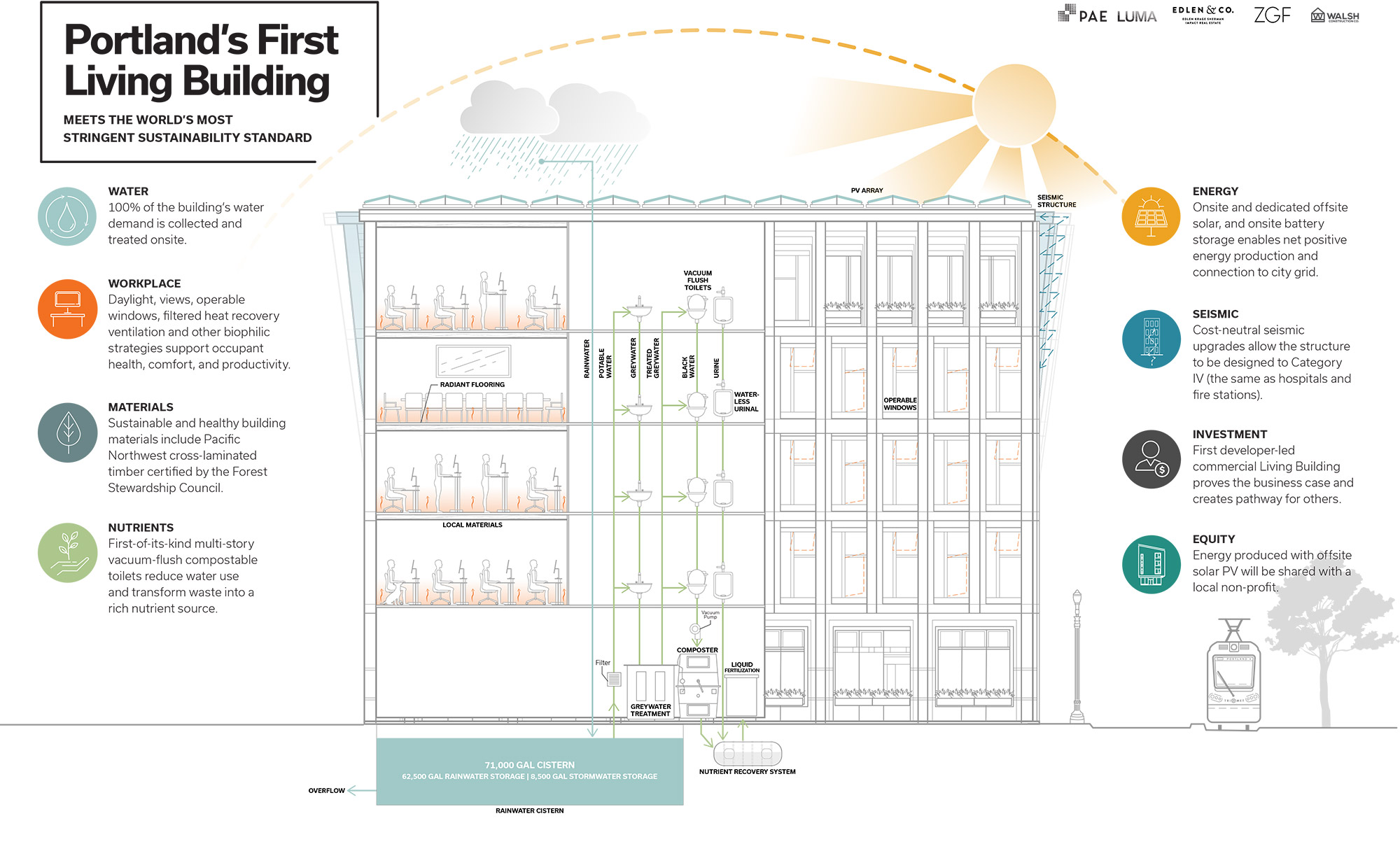

The PAE building is the world's largest commercial Living Building and the only one engineered to survive a magnitude-7.5 quake with barely a scratch.

Photo by Jamie Goodwick Portland Drone

One of several goals of the PAE Living Building team was to create a second-generation global model for commercial Living Buildings. The leaders of the 58,000-sq-ft project in earthquake-prone Portland, Ore., achieved their goal in April, when the International Living Future Institute declared the five-story office building, with ground-floor retail, as the world’s largest commercial building fully certified as a Living Building under ILFI’s rigorous Living Building Challenge sustainability program.

Beyond that, the PAE Living Building also takes developer-led Living Buildings to new levels. It is the first commercial Living Building that is led by a for-profit-developer; the first with its design and construction firms as investors; the first Living Building—and among very few office buildings in the world—engineered to sail through a magnitude-7.5 quake without business interruption; and the first Living Building to produce commercial-grade fertilizer from urine. The sales revenue from the fertilizer is $35,000 per year, according to PAE, the project's mechanical-electrical-plumbing engineer.

The five-story building, which is the 35th ILFI certified Living Building, also is the first Living office building in a dense urban setting. And its location in a national historic district came with restrictions on the architecture that complicated design.

The heart of all building systems of the PAE Living Building, including the potable water treatment and the computers.

Photo by Claire Chancey

“This was about hitting parameters and going beyond,” says Paul Schwer, president emeritus of PAE, also the main tenant in the building, which opened in September 2021.

Schwer, a 2020 ENR Newsmaker for masterminding the project, is an individual investor in the development, in addition to team members PAE, ZGF Architects and Walsh Construction Co/OR, the general contractor—mostly through donated fees.

The project’s development and technical achievements are many, including the first large-scale commercial installation of vacuum-flush toilets. But a big disappointment for the team is that though they carefully crafted a financial and design model for other private commercial Living Buildings, the office market collapsed as a consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Schwer and his PAE building colleagues are now in the process of investigating full—or close to full—certification for Living affordable housing, which has yet to be accomplished. “We are studying how to crack the pro forma on affordable housing,” says Schwer.

Additionally, the new focus for PAE and its Living Building cohorts is net-zero operational carbon emissions, rather than net-zero energy. PAE is studying net-zero operational carbon engineering, which may be counter-intuitive to the usual quest to right-size mechanical equipment, says Schwer.

His example of a net-zero operational carbon system would be the installation of a larger-capacity hot water heater than is needed for domestic hot water. The extra size would enable the heater to do double duty as a battery to store surplus solar energy.

“A hot-water battery is less expensive than a lithium ion battery,” says Schwer.

The performance period required for certification as a Living Building by the rigorous Living Building Challenge was delayed by the pandemic.

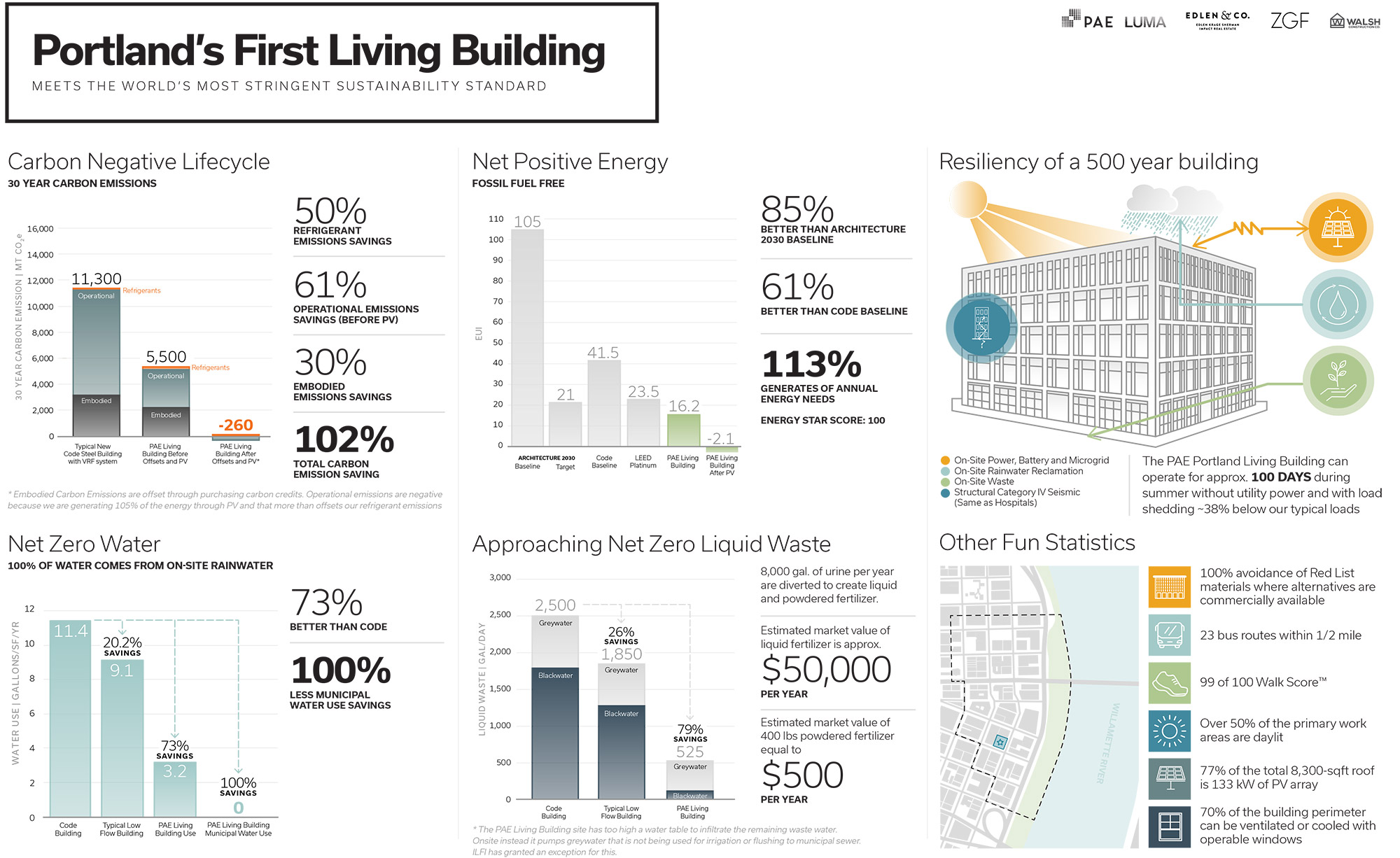

Graphic by PAE, ZGF

*Click on the image for greater detail

Pandemic Certification Delay

The pandemic and its work-at-home period delayed the certification process for the PAE building, which is now 85% leased. “The building is a bright spot in downtown Portland,” where only 40% of the office space is leased, says Marc Brune, PAE’s senior principal mechanical engineer.

For Brune and the PAE building team, the lessons learned along the road to Living Building certification were several. Overall, the performance period, which lasted about 18 months, was “pretty exciting and not easy,” says Brune, a veteran designer of Living Buildings, who says it is getting easier, but still challenging, to engineer a Living Building from a building systems point of view.

Brune offers insights on some of the bigger lessons, related to the technical features of the PAE Living Building:

Microgrid system: The building is connected to a utility network and the utility set a limit of about 50 kW of back-feed to the grid. As a way to make this work with the approximately 133-kW rooftop solar array, there is a 280-kWh battery to soak up the energy when it was not needed and had too much to back-feed.

“The battery let us slowly feed power back to the utility below the limit they set for us,” says Brune.

A snag was that the original battery system wasn’t able to meet all of the requirements for that back-feed. That meant that the battery couldn’t be used as intended during the performance period. During this time, the microgrid system was managing the solar production to keep the solar on, but below the production amounts that would cause a higher-than-allowed back-feed. It did this by basically disconnecting, or curtailing, parts of the solar system, Brune explains.

This requires a lot of active management of loads and production and initially the system was over-curtailing the energy production, resulting in much lower production than anticipated during the performance period, which started in the summer of 2022 and ended in April, he adds.

“We were able to work with the microgrid provider to improve the curtailment system by the summer of 2023 and significantly improve our production,” Brune says. “But the microgrid and the battery were a huge challenge and cost me some sleep during our performance period,” he adds.

Meanwhile, the good news was that the simpler solar array on the nearby affordable housing development, necessitated by limited roof space on the PAE building itself, was over-performing. The PAE building also was over-performing in terms of energy efficiency.

The PAE building can operate for approximately 100 days during the summer without utility power.

Graphic by PAE, ZGF

*Click on the image for greater detail

“We had anticipated about a 19 kbtu per sq ft per year [energy use intensity] and were operating around 16 EUI,” says Brune.

The net result was 113% net-positive energy production at the end of the performance period, which is a plus.

Building operators are in the final stages of recommissioning the microgrid system. “We anticipate it to be operating as intended this summer,” says Brune.

Graywater treatment system: The system requires ultraviolet treatment of the water to eliminate any potential coliform bacteria. The cast-iron piping for the sanitary system shed too much iron for the UV system to be effective in killing the bacteria, says Brune. Essentially, the bacteria could hide in the shadows of the iron particles.

The team ended up installing an iron filter prior to the UV light that fixed the issue. “In the future, I might consider a different pipe material if I know that UV treatment of the water will be needed,” Brune adds.

Composters and gnats: Composting systems often come with a gnat population. In the PAE building, the composters are in the same room as all of the other mechanical and electrical equipment and the computer systems. The gnats started finding their way into some of the sensitive electronic equipment, which caused concern, says Brune.

A few layers of protection were added. Some of the computers now have bug netting on the cage that surrounds the computer racks. “This worked well to keep the gnats out and didn’t significantly impact temperatures in the space,” says Brune.

The building operators also added pyrethrum, a natural plant-based insecticide, and nematodes, a microscopic beneficial worm, directly to the compost bins to control the gnat population. “They’re not gone, but at this point they’re not causing any problems beyond a slight nuisance of a few bugs flying around in the space,” says Brune.

Net-positive energy on an urban site: For future projects, PAE now understands more about how to make net-zero, or net-positive, energy work on an urban site with limited space for rooftop solar. The PAE team accomplished this through the "hand-printing" approach. In this case, that meant donating a solar array on a completely different project.

ILFI uses hand-print as the opposite of “footprint.” If a footprint—as in a carbon footprint—is something negative caused by people, a hand-print has a positive impact, explains Brune.

The team's donated solar array to a nearby housing project, which was part of the calculation for net-zero energy because of the limited size of the solar array on the PAE roof, produced about 226,000 kWh of electricity for the affordable housing building, which reduces their operating costs, according to PAE.

“I hope more projects will consider an approach like this that can create a broader community benefit in a building owner’s quest” for net-positive energy production, says Brune. “It’ll certainly be top of mind for us the next time we need more energy than our rooftop can provide.”

Water systems permitting: The PAE building is permitted just like any other water jurisdiction in Oregon. The potable water system was permitted relatively quickly, unlike at earlier Living Buildings. By about February 2023, “we were drinking the [treated] rainwater from the roof,” says Brune.

Gnats invaded the composters in the central utility room. Measures had to be taken to protect the computers and other equipment.

Photo by Claire Chancey

This was possible for a few reasons, he explains. The team had been through this before on earlier projects and knew the approach to take. Also, Oregon has a better code framework in place than for example, Washington state, and that allowed the Oregon Health Authority to more easily approve the system.

Brune’s warning to other teams: Nationally, the codes governing water and water reuse are not consistent state to state, making this process more difficult in some states and easier in others. "Best to study each state’s codes carefully," when embarking on a potable water treatment system, he advises.

Kathy Berg, ZGF’s partner in charge, says her big takeaway is that, with the right team and commitment, creating a Living Building “was a fun process.”

ZGF is currently the architect for three larger buildings but they are targeting ILFI Zero Carbon, not fully Living status. One is a 750,000-sq-ft market-rate and affordable-housing development with 42,000 sq ft of retail to serve the community. The building, called the Douglass, in Washington, D.C., recently topped out. It is on course to become the largest ILFI Zero Carbon multifamily building in the U.S.

For Berg, the PAE Living Building stands out among others as an “extraordinary project because of its aspirations.

“We’re ready to do the next one,” she says.