When New York’s Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) began procurement for the second contract of the $7.7-billion Second Avenue subway extension earlier this year, officials noted that “award of this contract is subject to funding availability, which requires the implementation of congestion pricing.” Following Gov. Kathy Hochul’s announcement June 5 that she was directing MTA to “indefinitely pause” rollout of the congestion pricing program in Manhattan, the future of that subway project—as well as a slate of other transit projects in New York City and surrounding areas—appears unclear.

Congestion pricing tolls for vehicles using local roads south of 60th Street in Manhattan were expected to generate $15 billion in revenue for MTA’s $54.8-billion 2020-2024 capital program, and anticipated congestion pricing bond proceeds represented more than half of the program’s remaining funds as of February, MTA officials said at the time. Under the 2019 law that directed MTA to implement the program, 80% of the revenue was to be spent on subway and bus system capital improvement projects, and the rest was to be split between Long Island Railroad and Metro-North Railroad work.

“It was the single biggest source of revenue, and the MTA was ready to start spending it,” says Sam Schwartz, a former New York City traffic commissioner and founder of traffic engineering firm Sam Schwartz Consulting LLC.

Hochul spoke about increased costs of living and declined office attendance since the COVID-19 pandemic in her reasoning for pausing the program, saying congestion pricing “risks too many unintended consequences for New Yorkers at this time.” The move drew praise from officials in areas such as New Jersey, Long Island and Westchester County, where many residents commute into the city by public transit or car.

“With the region not fully recovered from the pandemic and Long Islanders needing affordable access to Manhattan whether by car or train, Gov. Hochul’s pausing of congestion pricing is the right move at the right time,” said state Assembly member Charles Lavine (D), whose district includes parts of Nassau County on Long Island.

However, Schwartz questioned the reasoning, and says traffic in the city has recovered to pre-pandemic levels. Data from MTA and the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey together show traffic at their respective crossings into the city was up more than 44% in the first three months of this year compared to the first three months of 2019.

“There’s lots of activity going on in New York,” Schwartz says. “So I don’t buy the governor saying that she was worried about the middle class. It’s the middle class that will get the jobs. They’ll be the ironworkers and the laborers and the carpenters and the electricians who work on all these transit projects. You can’t build a subway tunnel remotely.”

The controversial congestion pricing program was facing at least eight legal challenges before it was due to take effect June 30, and MTA officials said they had already placed many capital projects on hold and halted advertisement for most new construction contracts. Jamie Torres-Springer, president of MTA Construction & Development, said in a statement in February that “congestion pricing is foundational to the MTA capital program.”

Impacted Projects

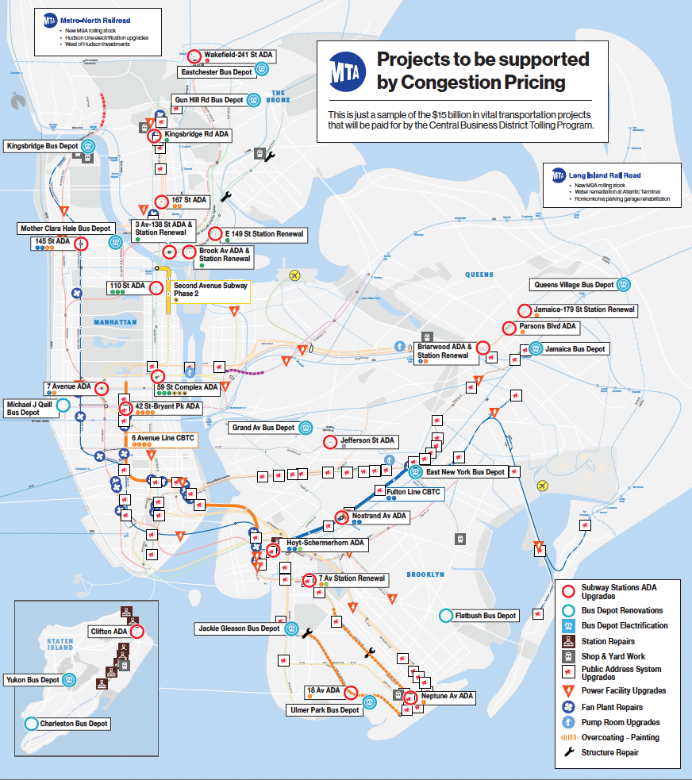

Projects on hold include signal modernization work on the Fulton line subway in Brooklyn and Sixth Avenue line in Manhattan, accessibility improvements at 18 subway stations and other upgrades at dozens more stations, installation of charging infrastructure for electric buses at 11 depots, electrification of the Metro-North Hudson Line south of Croton-Harmon and various state-of-good-repair works for aging infrastructure, according to MTA.

The largest project that is relying on congestion pricing is Phase 2 of the Second Avenue subway, which would extend the line 1.8 miles north and add three stations at 106th Street, 116th Street and 125th Street. MTA already awarded the first $182-million contract in January to C.A.C. Industries Inc. for utility relocation work, and in November the Federal Transit Administration agreed to provide $3.4 billion toward the work. In April, MTA issued a request for qualifications for the second contract, which included the line about the work relying on congestion pricing. It would cover tunnel boring and construction of structural shells for two stations.

Graphic courtesy MTA

Graphic courtesy MTAIn a video address, Hochul said she “remain[s] committed to these investments in public transit.” Officials “set aside funding to backstop” the MTA capital program and are “exploring other funding sources,” she added, without providing specifics.

However, transit advocates questioned what other sources could fill the $15-billion funding gap. Schwartz, who has promoted an alternative congestion pricing plan called Move NY, says that congestion pricing would have started generating millions of dollars per day from the start—while construction costs will only be higher in a few years when delayed projects may be able to advance. And other potential funding sources

“If she substitutes another business tax instead of tolls for congestion pricing, she’s going to run into tremendous opposition,” he says.

Several news outlets reported that Hochul had proposed raising the payroll mobility tax in New York City and surrounding areas to help close the gap. State lawmakers rejected the idea, Politico reported, and their legislative session was ending June 7. Carlo Scissura, president and CEO of the New York Building Congress, said in a statement that a mobility payroll tax increase “would only compound that colossal error.” He and others are pushing for Hochul to find a way to reestablish a start to congestion pricing.

“It’s the only way to ensure the MTA’s capital program is fully funded for the long term,” Scissura said.

Future Funding

The funding gap would likely remain a hindrance for MTA projects under its next 2025-2029 capital program, which is scheduled to be released Oct. 1, according to a report New York State Comptroller Thomas DiNapoli released last month. It warned that the funding gap for the next capital program could widen to $25 billion or more if dedicated revenue sources are not made available.

There are a number of ongoing projects that are likely to be included in MTA’s next capital program. For example, work is underway on the $382-million first phase of work to replace and rehabilitate the Park Avenue Viaduct in East Harlem, which carries Metro-North trains on the Hudson, Harlem and New Haven lines to access Grand Central Terminal. The 1.25-mile-long steel structure was built in 1893, and MTA officials say two sections of the viaduct need a full replacement. The current work led by contractor Halmar International is only replacing one of those sections.

Without the expected funding, MTA will likely face additional pressure to increase debt, which could impact its operating budget and lead to it raising fares, according to the comptroller’s report.

“There’s more at stake than just delayed projects,” DiNapoli said in a statement. “If the MTA covers the shortfall in capital funds by using its operating budget to pay for more borrowing, less money would be available for day-to-day operations and goals, like increasing service.”