The Atomic Age of the 1950s was dominated by the race between the U.S. and the Soviet Union to develop increasingly powerful nuclear weapons, as well as parallel efforts to better harness the power of the atom to produce electricity. But another front opened in 1957, when a group of U.S. nuclear scientists proposed using nuclear explosives for large-scale earthmoving, an effort known as Project Plowshare.

From the Archive:

A-Bomb Might Become Super-Excavator

March 6, 1958

Excavating With Nuclear Bombs

March 28, 1963

One of the first offshoots of Plowshare was Project Chariot, a plan by the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission to use nuclear explosions to excavate a harbor at Cape Thompson, Alaska. The scheme was pushed in 1958 by physicist Edward Teller, director of the commission’s Lawrence Radiation Laboratory (LRL), known today as Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory.

The proposed harbor was to have an entrance channel 6,000-ft long by 1,200-ft wide, leading to an oval “turning basin” more than one-mile long by one-half-mile wide. It was to be created by detonating four 100-kiloton thermonuclear bombs to excavate the entrance channel; and two 1-megaton bombs, to excavate the turning basin. The combined 2.4-megaton explosive yield would have been 160 times larger than the bomb dropped on Hiroshima. The lab contracted Holmes & Narver, a Los Angeles engineering firm, to design Chariot.

A civilian agency, the commission oversaw both military and non-military nuclear programs. The congressional Joint Committee on Atomic Energy controlled its budget.

ENR covered Project Plowshare with a series of news articles in the 1950s and 1960s, (see links right), as well as four supportive editorials between 1958 and 1962 related to the effort to evaluate the utility of nuclear explosives for construction projects.

Overshadowing Plowshare was the issue of radioactive fallout. Radioactivity from a 1954 hydrogen bomb test at Bikini Atoll in the Pacific Ocean had killed one crew member and poisoned several others on a Japanese fishing boat that was 85 miles from the blast.

Public concern about the danger of radioactive fallout grew in the following years, with chemist and biologist Linus Pauling, a Nobel Prize winner in chemistry, playing a prominent role. During one TV interview he stated that radioactive fallout caused cancer, shocking the audience.

Teller issued grants to a group of scientists from the University of Alaska to conduct extensive environmental studies for Chariot, hoping to co-opt them. The commission downplayed many of their findings on the potential negative impact of fallout on plant and animal life as well as on indigenous populations’ hunting activities, and it delayed final report publication by several years. Three of the scientists lost their jobs.

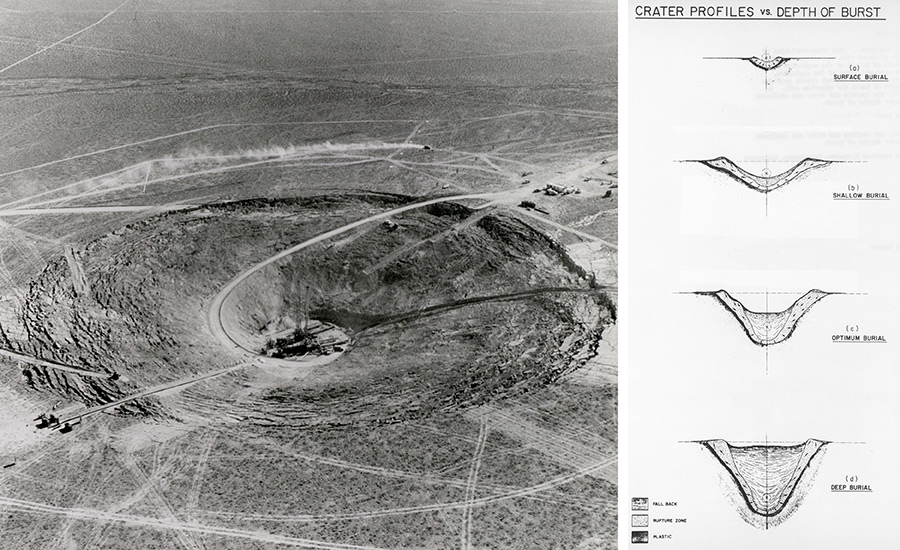

Project Plowshare's underground nuclear tests were conducted in the Nevada Test Site north of Las Vegas. One 100-kiloton device was detonated 635 ft underground where it displaced 12 million tons of earth.

Photo courtesy of U.S. Dept. of Energy

But several of the scientists shared concerns with Barry Commoner, a cellular biologist and early leader of the environmental movement, who disseminated their concerns within the scientific community beginning in 1961. That same year, an article in the peer-reviewed magazine Science discussed an increase in strontium-90 in children’s teeth following the first U.S. hydrogen bomb test in 1952.

A Second Panama Canal?

U.S. officials considered alternate routes for an alternative to the Panama Canal to be built using nuclear weapons.

Graphic courtesy of U.S. Dept. of Energy

Chariot was intended merely as a test for the U.S. government’s larger goal to build a sea-level canal across Central America, since U.S. military leadership feared Panama Canal locks were vulnerable to nuclear attack. The commission aggressively pursued related research and testing for over a decade.

Forty-eight papers on “possibilities and problems of the peacetime uses of nuclear explosions” were presented at a May 1959 Plowshare symposium held in San Francisco. They covered shock patterns, earth motion and thermal effects and avoidance of underground water contamination. One paper described excavating a 59-mile-long lockless canal, 600 ft wide and 60 ft deep, using 651 nuclear devices. In 1960, the Panama Canal Co. hired engineer Parsons, Brinckerhoff, Quade & Douglas to study nuclear weapons use to excavate a new canal route.

Project Carryall was a proposed highway and railroad excavation project that would have been a poster child for Plowshare if it had succeeded. The Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway approached the commission in 1963 to pitch use of nuclear blasts to excavate a two-mile long path through the Bristol Mountains in Southern California. The California Division of Highways wanted the same route for Interstate 40. Carryall died in 1966 due to nuclear test ban concerns and a looming deadline on Interstate routes.

Following several years of informal consultation between the commission and U.S Army Corps of Engineers, the two formed a joint program in 1962 to study construction problems related to nuclear weapons. Lt. Col. Robert W. McBride, then the Corps assistant director of civil works for nuclear planning, oversaw a crater study group at LRL. He and John Kelly, chief of the commission Division of Peaceful Nuclear Explosives, gave an extensive briefing to ENR reporters at Corps headquarters in Washington, D.C., in March 1963.

Eventually the U.S. Interior Dept., which had not been consulted, learned of Project Chariot and inveighed against it. At the same time, an above-ground nuclear test in Nevada in 1962 was found to have spread radioactive dust much farther than predicted, which further weakened support for Chariot. It was effectively cancelled the next month. The project’s final report, published by the commission in 1966, is said to have been “regarded as the first de facto environmental impact statement,” according to the book The Firecracker Boys by Dan O’Neill.

Project Plowshare's first underground test was Project Gnome in New Mexico, conducted in 1961. A 3.1-kiloton weapon was detonated 1,115 ft underground, creating a 99,000 cubic-ft cavern.

Graphic and photo courtesy the U.S. Dept. of Energy

*Click image for greater detail

Geopolitics and economic concerns played critical roles in restricting the the commission’s advancement of Plowshare. Disarmament talks between the U.S., USSR, Britain, France and Canada failed to reach an agreement. Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev unilaterally offered to suspend nuclear testing in 1958 to pressure the U.S. into reciprocating. President Dwight D. Eisenhower agreed to a one-year moratorium on new nuclear tests in October 1958. This resulted in several planned underground Plowshare test explosions to be put on hold.

Louder Than Bombs

Most military and Plowshare nuclear tests were conducted at the Nevada Test Site, a 680-sq-mile stretch of mountainous desert terrain in Southern Nevada northwest of Las Vegas. Project Sedan in 1962 was Plowshare’s first nuclear cratering blast. A 100-kiloton device was detonated 635 ft underground where it displaced 12 million tons of earth and left a crater 1,300-ft across and 320-ft deep and sent up a cloud of debris three miles high. Publicly, the commission emphasized the positive aspects of the test, saying that the crater trapped 95% of the radioactivity while the remainder fell close to the test site. But the radioactive dust cloud was twice as big, rose significantly higher and “deposited nearly five times as much fallout on and near the test site” than the agency anticipated, according to the book Project Plowshare by Scott Kaufman.

Despite suffering defeats on Chariot and Carryall, the commission pushed hard for Project Gasbuggy, in which the agency, U.S. Bureau of Mines and El Paso Natural Gas Co. sought to demonstrate the feasibility of enlarging natural gas fields with nuclear weapons. In 1967, a 26-kiloton blast that was detonated 4,240 ft underground in New Mexico made a cavity 150 ft in dia and 333 ft high and created 2 million cu ft of space for gas to enter. Initially the results appeared exciting, but tests of the cavity a month later showed the blast had changed the composition of the gas to a lower purity and infused it with radioactive tritium, rendering it unsalable.

The surface result of an underground nuclear explosion conducted at the Nevada Test site in 1961.

Photo and graphic courtesy U.S. Dept. of Energy

*Click image for greater detail

U.S.-Soviet test ban talks in the early 1960s led President John F. Kennedy to halt Plowshare tests to avoid jeopardizing an agreement. To avoid losing momentum on Plowshare, the commission substituted TNT for nuclear devices on several tests, managing to continue collecting useful data. But Glenn Seaborg, the new agency chair in 1961argued that the proposed U.S.-Soviet treaty did not prohibit all underground tests. Kennedy signed the limited test ban treaty in October 1963. The two superpowers would open broader nonproliferation talks the following year, but the administration of President Lyndon Johnson delayed many Plowshare tests to avoid jeopardizing the talks.

Plowshare would suffer budget cuts during the Johnson era as well, due to increased spending on the Vietnam War and on domestic War on Poverty programs. The administration of Richard M. Nixon inherited a sizeable budget deficit that led to a recession in 1970, and even more cuts. There were 27 Plowshare explosions between 1957 and 1973, which consumed increasing amounts of commission funds.

ENR reports indicate that the hubris of commission officials, their evasiveness on the subject of radioactive fallout, diplomatic priorities of four successive presidents and rising environmental consciousness of the American public all combined to doom efforts to use nuclear weapons as tools for mass excavation.