In Summer 2023, the payment system for a small office and warehouse project that Beck Properties was developing for itself in South St. Paul, Minn., seemed to be running smoothly. Emails were criss-crossing back and forth and paper checks were landing in mailboxes.

Each pay application required prime contractor R.J. Ryan Construction to sign and send an unconditional receipt and waiver of lien rights to a funds disbursement agent, FSA Title Services, which worked for Beck Properties’ bank lender. After an initial $1.57-million payment, R.J. Ryan sought full or partial payment for costs such as grading and excavating ($26,600), concrete and masonry ($80,000) and steel deck and joists ($442,000).

The contractor’s project manager, Jalen Stay, asked in August that Beck Properties switch from the usual system and transmit funds electronically for money due—about $735,000—under payment application 13. The firm needed funds faster, he wrote, because other payments received the usual way had not yet been credited to its account. “Hi Rick,” he wrote in an email dated Aug. 15 to a Beck Properties staff member. “Can we have payments remitted electronically as we currently have numerous uncleared checks on hold?”

That triggered emails about verification required by FSA Title Services. These culminated with Jalen Stay filling out a special payment change request form and scanning a notarization into the email sent to FSA Title. Feeling it had everything it needed, the title services firm released the $735,000 to the account number provided by R.J. Ryan.

The money was never seen again. As things turned out, email Jalen Stay was not the real Jalen Stay. The email version was a criminal con artist impersonating the real Jalen who, after apparently gaining entry to R.J. Ryan’s email system, quietly watched as the project conversations and payment requests went back and forth—waiting for the right moment to slip in and pretend to be the real Jalen. That allowed the con artist to trick the developer into sending the funds to an account only the fake Jalen had access to.

A crime wave is rolling through the world’s email servers, and cybercriminals have found a lot to like about construction’s busy offices and Byzantine payment practices. In recent years, such criminals have siphoned considerable funds from a Massachusetts high school, a California door supplier and a U.S. Army Corps of Engineers fence replacement project in California, among others. The average loss from such email-based fund diversion frauds in all industries is less than $175,000, says research by NetDiligence. But many are way above average cost and far above claim payout limits set by insurers trying to limit their own risks.

After the Minnesota warehouse payment theft was discovered, new problems confronted the project team: Who was responsible? Also, whose insurance policy could, via a claim, help fill the gaping financial hole left by the theft?

In many such policies, the crucial sublimits—an amount smaller than the total policy limit tied to a specific peril or type of loss—are low. In the warehouse case, FSA Title’s liability policy from Hanover Insurance Group paid Beck Properties its limit of $100,000, and a separate cyber insurance policy with At-Bay/Trisura Specialty insurance will apparently pay another $100,000. But all of that money will be used for legal expenses for the lawsuits involving Beck Properties and R.J. Ryan. The former apparently settled with subcontractors that had filed liens against the property.

Confusion over policy coverage is not unusual. Some of it arises from insurer decisions starting 10 years ago that schemes where cybercrooks used phony emails would not be treated as a cybercrime along with ransomware and malware attacks. Insurers instead prefer to put such crimes into separate policies that offer somewhat more generous coverage, alongside the traditional business crimes insurance for physical thefts and embezzlement.

There’s a certain amount of sense in separating “business email compromise,” as it’s often called, and related issues, from other cybercrimes.

With general ransomware attacks and other breaches, there are many unique losses involving the policyholder, third parties, business interruption claims and such things as cost to replace hardware. Business email compromise is narrower and more limited, but other types of cyber insurance-related claims also come into the picture. So the separation is rarely complete.

Prior to 2018, the majority of courts held that losses from social engineering fraud—a type of fraud where victims are tricked or coaxed by a person into sending money or granting access to secure systems—were not covered under computer fraud insurance, according to Gabriella Scott in an online essay in the Villanova University Law Review. Attorneys for policyholders had sometimes tried to get insurers to pay for social engineering schemes under cyber policies, hoping for a higher payout limit.

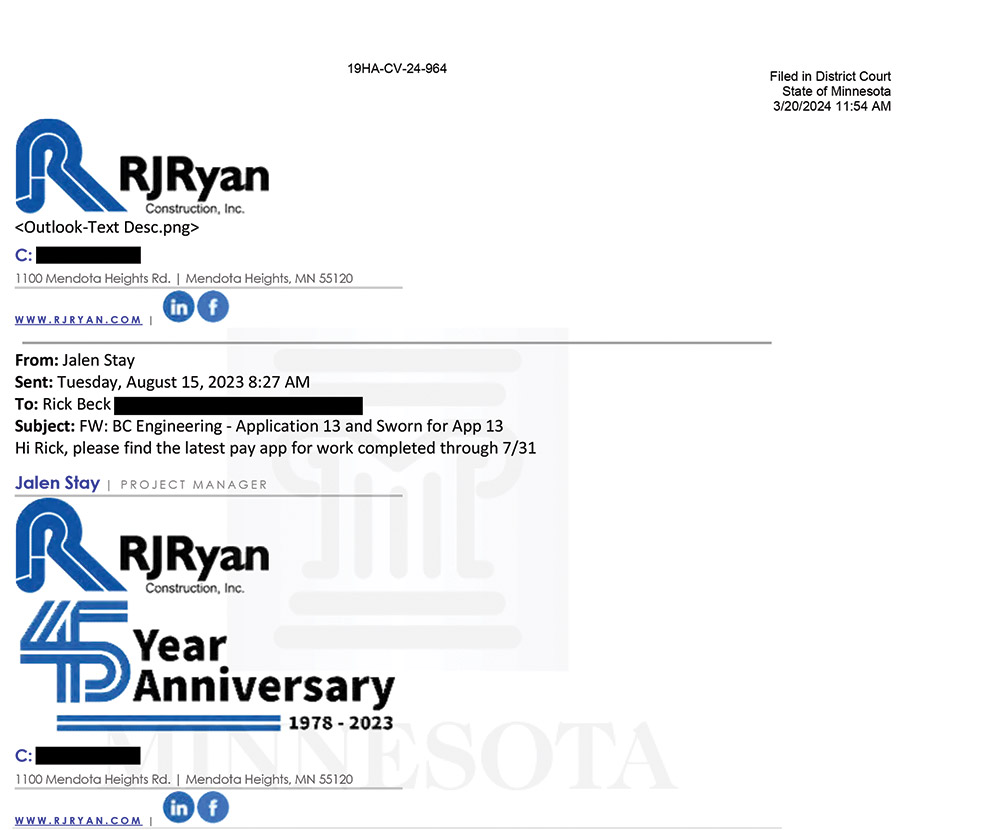

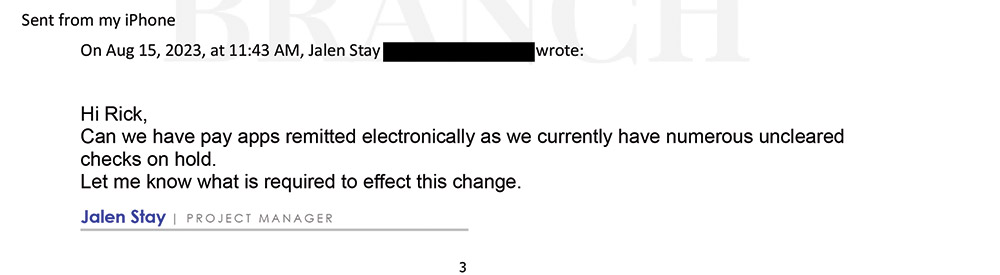

The Build-Up: Emails 1-4

*Click on the images to see them clearly

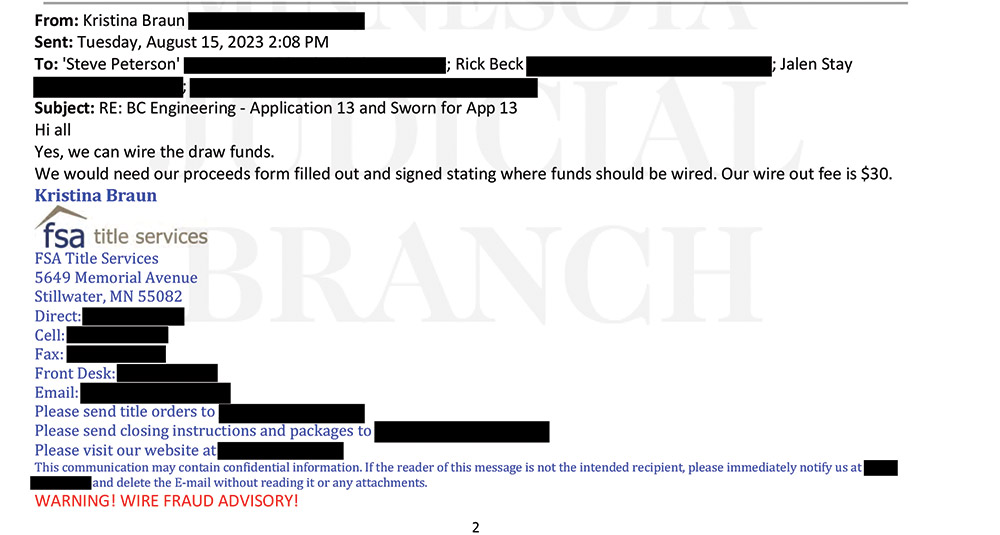

Email 1

Email 2

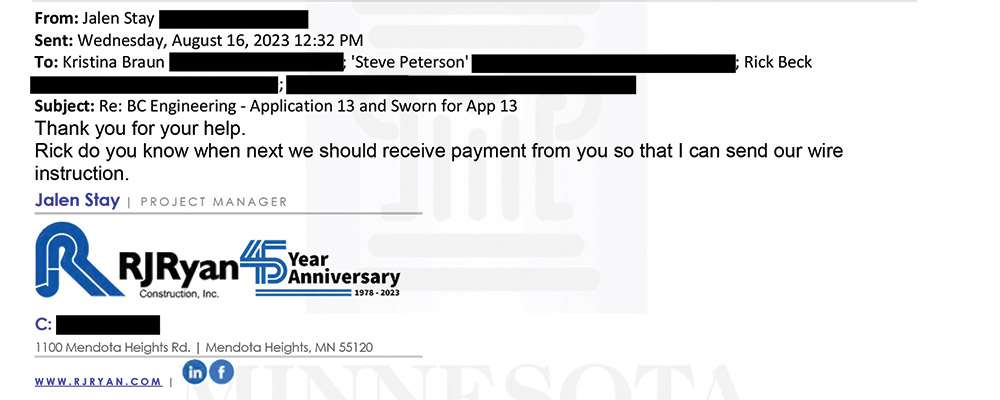

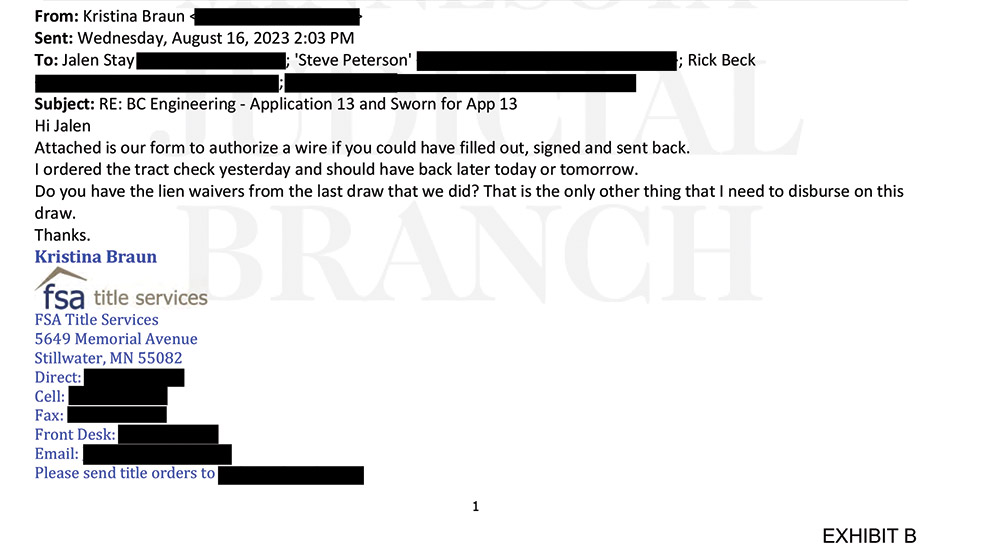

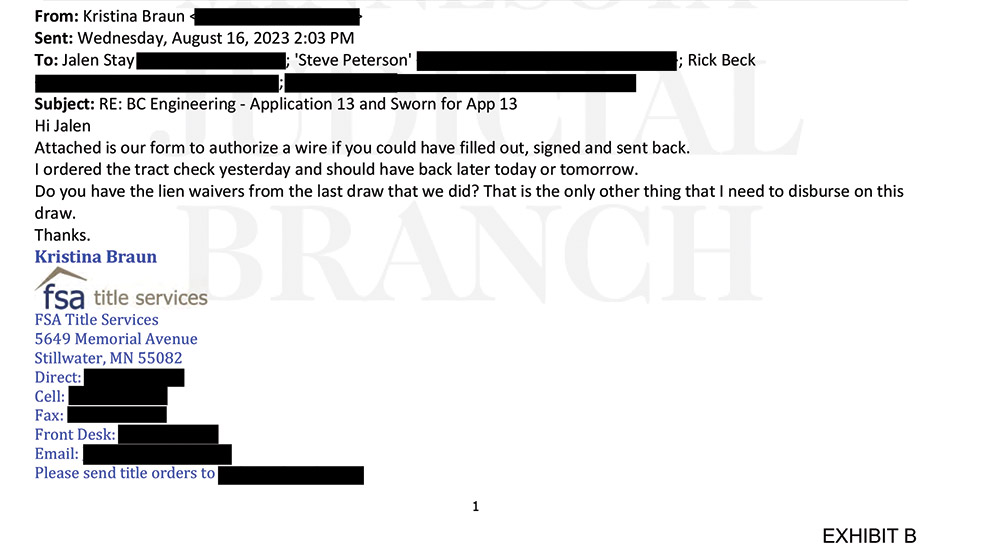

Email 3

Email 4

The lawsuit docket in Minnesota state court, where developer Beck Properties is suing contractor R.J. Ryan and FSA Title Services, contains an affidavit with eight emails key to the fraudulent payment diversion of project funds. It can’t be known for sure, but it is likely that Email 2, where Ryan’s project manager asks developer Rick Beck for an electronic payment, is almost certainly a fabrication by a criminal. Beck refers the matter to his lender’s loan officer, who turns to FSA Title Services’ Kristina Braun. Her emails contain a fraud warning beneath each signature block.

Original email images from Minnesota State Courts

The separation from other cybercrimes meant insurers would be able to evaluate separately the risks of social engineering crimes carried out with email, compared with other types, such as ransomware. That helps insurers model the risks and claims and pricing accordingly, wrote Scott.

Tom Ricketts, a managing director of insurance broker Aon, wrote last year that due to the frequency of employees falling victim and the severity of claims, insurers have sharply curtailed annual social engineering sublimits—keeping some as low as $10,000 and often never higher than an annual maximum of $250,000. While his observations were based largely on the broker’s own experience, the piece’s title speaks to the thornier unresolved issue: “When Is a Cyber Crime Not a ‘Cyber-Crime’?”

Separating email fraud from cyber insurance, it turns out, created an insurance jigsaw puzzle over how the two actually still fit together. “No other type of insurance interacts with so many other coverages,” says Ryan Mercer, vice president for cyber at broker McGriff. “Classing email funds transfer fraud under crime policies involves many complications.”

An important aspect is whether a cyber or a crime policy should serve as the primary layer of coverage, with the other kicking in when primary limits are exhausted. This takes advance coordination to avoid being charged twice for retentions, the deductibles such policies require.

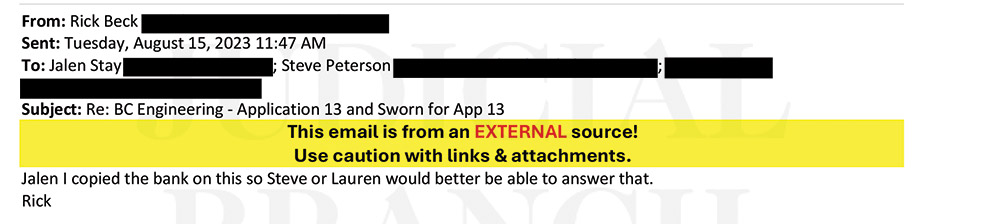

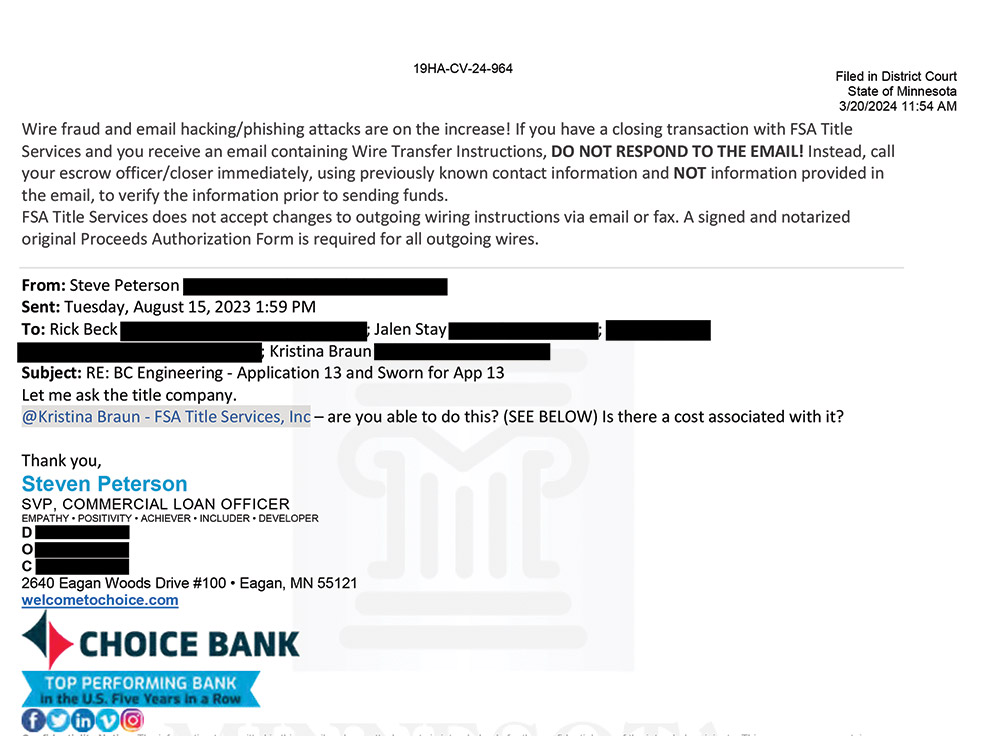

The Sting: Emails 5-8

*Click on the images to see them clearly

Email 5

Email 6

Email 7

Email 8

FSA Title's Braun mentions in Email 5 that a signed proceeds form is needed. In Email 6, the con artist, impersonating Ryan’s project manager, asks Beck when the payment will be made “so I can send you our wire instructions,” cc’ing FSA Title and making it seem a more urgent matter to act upon. The next day the impersonator sends the form to FSA Title, and with Email 8, again adds urgency by asking, “Will wire be disbursed today?”

Original email images from Minnesota State Courts

There are also definitional issues. Tom Srail, executive vice president at broker Willis Towers Watson, says that some cyber insurers use the terms social engineering fraud, funds transfer fraud and invoice manipulation fraud “somewhat interchangeably, while others define them to mean different events with potentially different coverage sublimits and terms.”

Some confusion arises from insurance industry metaphysics. One example is the question of what is a direct or indirect loss. That issue may hinge on whether a company has custody of the funds and whether being owed money that does not ever reach recipients qualifies as a direct loss. Some policies do not include indirect losses, so a focus of some disputes is whether funds are literally in the possession of the insured, or simply owed. There can also be questions about whose email system was breached and who was fooled or failed to act with sufficient caution to protect a system.

Although the matters have been sorted out somewhat, and some insurers offer customers unified insurance policies and simplified application forms, brokers and attorneys are still fond of saying that there are no standard policies for these types of risks.

But standardization may be a big ask in the evolving risk landscape. Last year, cybersecurity firm SecureWorks reported that business compromise incidents doubled in 2022. What could happen next is disconcerting. From the criminals’ perspective, easy-to-use artificial intelligence-assisted text generation tools such as ChatGPT and Google’s Bard are almost ready-made for those looking to create believable fraudulent documents needed to manipulate victims, not to mention other rapidly advancing generative tools that can create fake images or convincingly imitate voices.

“No Other type of Insurance interacts with so many Other coverages, and Classing Email funds transfer fraud unDer crime policies involves Many Complications.”

- Ryan Mercer, Vice President, Cyber, McGriff

In the costliest known instance of possible AI-related fraud, an employee of London-based global engineer Arup working in Hong Kong was duped with the aid of deepfake video call images. This deception helped trick the employee into sending payments to accounts created by criminals, according to various media reports in May. The reported loss, $25 million, prompted Arup Chief Information Officer Rob Greig to note the increasing number, regularity and sophistication of the schemes.

Cybercrimes often go underreported, but news of contractors or owners getting defrauded does surface occasionally. The Arlington, Mass., school district, which is completing a $250-million high school, was defrauded out of $434,000, but says it will only receive $100,000 from an insurer. No additional details were provided by a representative of the town manager.

One tactic that fooled companies in the South St. Paul warehouse con job—switching bank data and a fabricated notarization—is a type of fraud that does not rely on social engineering alone to manipulate people. Instead, the cybercriminal takes advantage of someone simply not noticing that the criminal’s bank account number has been inserted in place of the intended recipient’s on what appears to be a legitimate invoice—easy to miss in long back-and-forth email exchanges.

Chris Quirk, an insurance broker at Turnersville, N.J.-based ARC MidAtlantic Excess & Surplus Inc., says “email manipulation scams are far more popular in 2024 than social engineering because it is harder to detect.” The payments are regular or expected and the only difference is in the banking details. There is also more lag time in discovering the fraud, usually when a victim follows up on an unpaid invoice and the client insists it has already been paid out. “That gives the hacker more time to get away,” he adds.

A typical crime policy won’t cover invoice manipulation, as far as Quirk can tell, and although it can be covered under some cyber insurance policies, the payout limit usually only goes up to $250,000.

Cybercrooks were able to divert $434,000 from a new high school in Arlington, Mass., but the town was only able to collect $100,000 in its insurance claim.

Photo courtesy of Arlington High School Building Project, Town of Arlington, Mass.

How Cyber Insurance Got Started

Cyber insurance was born when Steven Haase, a former broker, helped insurer AIG write the first internet security liability policy in 1997. Adoption came slowly, with terms and conditions and prices varying widely. As more insurers jumped into the market, conditions remained soft, meaning policies were plentiful with reasonable terms and limits. One standard exclusion, used for war-related acts, became common.

In 2017, several big cybersecurity calamities—including a major data breach at credit reporting agency Equifax and a rampant ransomware attack called WannaCry that affected hundreds of thousands of computers and servers—showed insurers the potential for massive losses. Around the same time, some property insurers became convinced they could face claims for “silent cyber insurance,” meaning customers and courts would interpret policies in a way that policyholders could make successful claims for losses from disruptive hacks to systems controlling equipment or property. So insurers tightened terms to eliminate coverage under property policies.

“If R.J. Ryan had a strong cyber policy with invoice manipulation coverage, they are very likely to have been able to buy up to $250,000 [in a coverage limit].”

- Chris Quirk, Broker, ARC MidAtlantic Excesss & Surplus

Some insurers adopted more exclusions to limit the amount they were obligated to spend or provide for improvements to a company’s cyber defenses or software. Addressing other risks, insurers started inserting terms into policies that required companies to observe stringent security practices, make timely notification of a loss and promise to help the insurer investigate the claim by turning over all records or assisting it in collecting money from another party at fault.

Failure to comply with any of these rules could be costly. “If you don’t follow the terms of the insuring agreement to a T, the insurance company may deny the claim,” says Luma S. Al-Shibib, a shareholder at law firm Anderson Kill. In most cases, she says she is able to negotiate settlements when insurers deny claims.

In 2020, what was a 15-year softening market for cyber insurance quickly hardened in response to the mounting cyber risks amid the shift to at-home work and the potential for isolated and less-secure home computers to create vulnerabilities. Premium increases as much as doubled between 2020 and 2022 for the same risks and payout limits. In the past year, pricing rates have actually declined “although they are not as low as pre-2019,” says Willis Tower Watson’s Srail. He says exclusions and sublimits “still exist in some markets, but many of the hard-market restrictions, such as ransomware sublimits or exclusions, are nearly gone.”

Meanwhile, the frequency and severity of business email compromise and social engineering losses are holding steady, says Nick Economidis, a senior vice president of eRisk at insurer Crum & Forster. He theorizes that “companies are getting better at fundamental controls, which minimize or prevent losses in most places.” But where controls are not in place or can be defeated, “the bad actor exploits that because 89% of the time they won’t be successful, and so they want to make as much money as they can.” ARC MidAtlantic’s Quirk says the pattern he sees in email-related fraud is criminals “sitting around and waiting for the big invoice to come through and attack that.”

Anatomy of a Payment Diversion

Related to the Beck Properties case, the project team and bank lender for the warehouse it was developing in South St. Paul, Minn., in summer 2023 had typical payment procedures. FSA Title, which would disburse funds a bank agreed to lend Beck for the project, had a Title Agent’s Errors & Omission Policy with Hanover Insurance Group and a cyber insurance policy from At-Bay/Trisura Specialty Insurance Co.

FSA Title’s emails even contained a prominent warning about phishing and fraudulent funds transfers. But the stolen payment was not detected until after roughly one month had passed, court records show.

From its two insurance policies, FSA Title learned it would only net $200,000—after its deductibles had been used up—that the firm’s attorney told the court would all be used for its legal defense costs. To understand how claims are treated by insurers, it is useful to read what its insurers told FSA Title.

When Beck Properties made a claim against Hanover, the insurer evaluated the claim by drilling into the specifics of the policy. Hanover’s senior specialty claims manager stated in a letter to FSA Title's Kristina Braun that it would pay out the limit of $100,000 under the policy’s “theft of funds supplemental coverage,” which provides reimbursement for the “theft, stealing, conversion or misappropriation of funds” that were under Braun’s “custody and control.”

But Hanover “has no duty to pay out more” or the full stolen $735,000 sought by Beck Properties, the insurer claims manager noted, because the policy specifically excluded claims arising out of “trick, artifice or misrepresentation of fact … including funds transfer fraud.” Hanover also had no duty to pay legal defenses for FSA Title on this element, the insurer said. A claims specialist for cyber insurer At-Bay/ Trisura was similarly blunt with FSA Title when it made a claim under its cyber policy. The insurer apparently agreed to pay $100,000, the policy’s sublimit for financial fraud. The policy had a $1-million limit that only kicked in if FSA Title’s own email or computer system was breached.

Aon’s Ricketts did not comment on the specifics of the Minnesota case. But he notes that both crime policies and many cyber policies now offer social engineering fraud coverage for when employees voluntarily part with money after being duped by a criminal third party. “It is important to study the coverage carefully because the circumstances or situations that the policy covers are usually very carefully and precisely defined,” he says. “Many of the lawsuits over coverage for these types of incidents are the result of the insured not understanding how the coverage works and what conditions, limitations or exclusions might apply.”

There are also distinctions between social engineering and invoice manipulation affecting claims. Coverage for the latter requires that a hacker access a network and send fake invoices or payment instructions, says ARC MidAtlantic’s Quirk. For a social engineering incident to be insured, he says a hacker anywhere in the line of communication must impersonate a third party (depending on scope of coverage) while sending fake invoices or payment instructions.

What is not clear yet from court records is what insurance R.J. Ryan had. Because it is likely that the contractor’s system was breached, “if R.J. Ryan had a strong cyber policy with invoice manipulation coverage, [it] very likely would have been able to buy up to $250,000” in a coverage limit, says Quirk.

In Beck Properties’ negligence, fraud and breach-of-contract lawsuit in state court against R.J. Ryan Construction and FSA Title Services, the developer alleges that the contractor failed to “exercise due care” in maintaining and securing its email system and that the company “could have and should have” immediately recognized that its system had been compromised. Beck’s complaint also accuses FSA Title Services of failing to adequately scrutinize the funds request, as required under its contract, or to comply with the company’s own policy of relying only on original copies of requested documents, including a notarization.

Neither R.J. Ryan Construction nor FSA Title Services could be reached for comment, and an attorney for Beck Properties’ declined to comment. FSA Title Services President Kristina Braun said in a March 20 court affidavit that the firm had performed all required diligence responding to the requested pay switch.

Insurers have in some cases provided excess insurance coverage with a high limit that could come closer to meeting the full loss in a social engineering funds loss claim. U.K.-based insurer Beazley Group in 2017 introduced a policy “to address the shortfall,” providing coverage of up to $5 million in excess of underlying coverage of at least $250,000. The coverage was considered a surplus line—for unique risks. Such a policy may have to be requested when a broker does not suggest it.

Separating email-related fraud from cyber insurance, despite the confusion, may end up being for the best in the long run. Properly understood perils help insurers understand real risks. Wrote Scott in her law review article: “Disentangling computers from the crime or activity involved” in social engineering fraud “will prepare the insurance litigation field for a future in which technology is ubiquitous in all aspects of corporate and daily life.”