Bernard Amadei had a decision to make in 2002 after visiting a Costa Rica hydroelectric project on which he was asked to consult. The University of Colorado-Boulder civil engineering professor and geotechnical expert could have accepted the invitation and nicely supplemented his academic salary. But Amadei could not ignore the fact that the huge project would displace many locals from their homes and violate a basic engineering dictum, “Do no harm.”

Choosing to forego that opportunity may have cost the educator short-term, but it propelled his quest for a new direction in engineering that today is enriching the daily lives of the world’s poorest communities and the work lives of thousands of industry practitioners, educators and students who share his vision—and also are taking it in new directions. Amadei’s experience in Costa Rica—and a previous one in Belize, helping his immigrant home landscaper bring water supply to his native village—helped launch an engineering movement that some say is a phenomenon that will mold the next generation of industry leaders.

The unassuming France-born educator, seemingly content in his tenured existence, says he never intended to create Engineers Without Borders-USA. But he realized, as have his supporters, that the excitement shown by students for a volunteer organization allowing engineering skills to benefit a larger universe was critical, or the profession risked losing motivated talent. Amadei knew the group’s time had come. “When the train passes by, you have to get on it, even without a destination,” he says. “Students were tired of just doing problems 5.1 to 5.5.”

From being a “funky Boulder” group with one chapter, a few CU student members and even fewer volunteer staff in 2002, EWB-USA has grown into a nationwide juggernaut of 12,000 members in more than 225 established and developing campus and professional chapters across the U.S. with a $3-million annual budget, not including project funding.

Participants now work on hundreds of small-scale but still challenging infrastructure and development projects in poor communities across the globe. Their efforts, they say, have impacted more than 600,000 people in 41 nations, including the U.S. For example, EWB-USA students from tiny Carroll College in Montana are mentoring middle-school students from the nearby Blackfeet Res- ervation to embrace engineering as a way to reduce high school dropout rates.

A small core of mostly Denver-centric industry believers has grown into a financial support network of engineering’s key professional associations and companies that see the light, including Boeing Corp., Autodesk and Abbott Laboratories. We support EWB-USA for what it does,” says Herbert Lust, Boeing’s strategy-integration director for global corporate citizenship. “But it develops leadership and mobilization skills, and that is a beautiful plus.”

Amadei also sought to leverage EWB-USA’s impact by linking it with similar groups in other countries. The networking led to the formation, in 2005, of EWB-International, a confederation of more than 40 EWBs from Denmark to India to Palestine. Former Corps of Engineers chief and EWB-USA adviser Henry J. Hatch sees group members around the world carving larger roles as nation builders and peacemakers.

The academic also has brought EWB into class, launching a sustainability- focused “engineering for developing communities” program in CU’s engineering school. It will soon grow with a $5-million investment from Mortenson Construction, Minneapolis, and chairman Mort A. Mortenson and his wife, Alice, that was announced on March 18. “This expands the whole concept of engineering beyond the technical,” says Mortenson, a CU alumnus. “It is something our engineers would get excited about.”

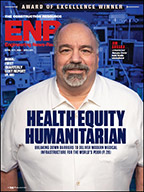

For his vision and perseverance in bringing Engineers Without Borders-USA to reality, for his impact on the future of developing communities, and for fostering a sea change in the study and practice of engineering that has catapulted its prestige and appeal to a new generation, the editors of Engineering News-Record have selected Bernard Amadei to receive the 2009 Award of Excellence.

“ This expands the whole concept of engineering beyond the technical.”

— MORT A. MORTENSON, CHAIRMAN, MORTENSON CONSTRUCTION CO., MINNEAPOLIS

EWB-USA was not the first group to adopt the “without borders” brand, nor do all EWBs accept its approaches. But statistics Amadei cites from memory of billions around the world still without clean water, proper sanitation or adequate housing emphasize his frustration. “Bernard is a purist and thinks everyone should work together,” says one longtime EWB-USA colleague. “It is almost a naive purity.”

The group also still feels the pain of its fast growth, as it struggles to effectively manage participants and projects and present itself to prospective donors as a serious organization worthy of support. The group’s 2007 link with the American Society of Civil Engineers, an organization with 146,000 members and 150 years of association management experience, is expected to remedy those hiccups.

ASCE agreed to commit $1 million to EWB-USA in 2008-09. The two groups are adapting to each other’s mission and methods. “ASCE had the clout to do something,” says Dan Harpstead, EWB-USA board treasurer and principal of Kleinfelder Inc., San Diego. “It saw this was a place where it could fundamentally engage students for a lifetime career.”

New Interest

EWB-USA has indeed brought engineering to life for industry “millennials,” particularly women who were not enthused about it. “EWB projects are very empowering to students when they see how much they are truly capable of doing and what a difference their knowledge can make in someone else’s life,” says Amy Mikus, a graduate civil engineering student at the University of Michigan-Ann Arbor and veteran of water projects in rural Guatemala. “Our generation will have to be global engineers, and any exposure to the wider world early in our careers will have a major impact on how we think down the line.”

Listening to Amadei, 54, teach an upper-level engineering-geology course, the subject he has taught since arriving at CU in 1982, there is clear indication that he wants to influence young engineers’ thinking. Sprinkled into a lecture on rocks and minerals is an admission by the respected and well-published academic that he “never could learn chemistry.” Amadei goes on to emphasize the pollution impacts of aluminum extraction and the “geopolitical component” of global copper mining.

Amadei’s technical competence is widely known, through two books, more than 150 technical papers and scores of industry appearances. His technical achievements gained him entry last year into the exclusive National Academy of Engineering, one of only 10% of its 2,400 members who gain that status before age 60. But his newer exploits earned him, in 2007, the Hoover Medal, bestowed by the five major engineering societies, as well as a $125,000 award from the Heinz Foundation, funded by the estate of John Heinz, the late politician and food conglomerate CEO. Amadei donated about half to EWB, with CU matching it.

“Someone with his success could have achieved more status at the university. He didn’t,” says John K. Bennett, a CU computer-science professor, director of a campuswide interdisciplinary learning program and an early EWB-USA supporter. “He’s the most selfless individual I ever met.”

But Amadei’s time commitment to EWB and to the Engineering for Developing Communities (EDC) curriculum was not as well received initially by all faculty colleagues and superiors who felt it distracted him from needed research and undercut faculty harmony. Some past performance reviews reflect that. But JoAnn Silverstein, current chairwoman of CU’s civil, environmental and architectural engineering department and a 27-year colleague, credits “his persistence, timing and ability to engage our best constituency, the students.” Amadei himself points to his tenure protection that allowed him to “play the game” to pursue the EWB and EDC ventures.