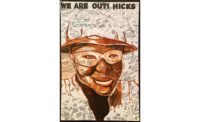

Willard Hackerman, who likely set industry longevity records as a construction company employee and as CEO, died on Feb. 10 in Baltimore.

The 95-year-old, who worked for locally based Whiting-Turner Contracting Co. for more than three-quarters of a century, also led the firm to the top ranks of national building contractors in his 59 years as chief executive.

Hackerman also pushed for the resurgence of the engineering school at Johns Hopkins University—his alma mater—as a separate school named for his CEO predecessor, Whiting-Turner co-founder G.W.C. Whiting.

But as a builder and philanthropist, Hackerman left his a bigger mark on the school, the city of Baltimore and elsewhere.

He died of natural causes, Timothy Regan, 58, his successor as president and CEO, told ENR. Formerly executive vice president for the last five years, Regan is a 34-year company veteran and a civil engineer.

Regan cites Hackerman's "steady hand and inspirational leadership."

Under Hackerman's long tenure, Whiting-Turner's logo was ubiquitous in Baltimore, with the firm building many locally iconic structures, such as the city's Inner Harbor, sports stadiums and medical facilities.

He also played a key financial role as developer or benefactor—or both.

A Feb. 10 Baltimore Sun editorial said some projects, particularly those done with former Mayor William Donald Schaefer, "tested the limits ... of ethical constraints of government contracting," but Hackerman "was the 800-pound gorilla of Baltimore economic development and philanthropy."

The Baltimore Business Journal questions the status of a planned $500-million downtown arena-hotel in which, it said, the former CEO was to have provided $200 million that Whiting-Turner was to have built.

Even while avoiding the latest high-tech business tools, Hackerman pushed Whiting-Turner beyond the region and into work such as bridge upgrades and wastewater treatment construction.

The 2,100-employee firm ranks at No. 15 on ENR's Top 400 Contractors list, with $3.78 billion in 2013 revenue, three-quarters of it in building construction, and is listed at No. 117 on Forbes' list of the 225 largest privately owned U.S. firms.

For all of his public largesse, Hackerman avoided many media interview requests, mostly eschewed involvement in industry groups and was known to reject pitches from consultants. One recalls being hung up on. An executive of a large building contracting firm said Hackerman also was not keen on the the firm doing joint ventures.

But reverence for "Mr. Hackerman" was a mainstay of the Whiting-Turner culture.

"There was one guy referred to as "The Boss," says Adam Gross, principal of Baltimore architect Ayers Saint Gross and a frequent project collaborator. "People below made decisions, but not without checking with him first."

Hackerman touted the large number of professional engineers on staff for a contractor, and strongly supported women, but marketing was not big at the firm, says Gross. "There was no razzle-dazzle," he says.

Gross says he protected employee jobs during the recession and that, while staff were "scared of him," they were devoted. "I saw 60-year-old men crying at his [Feb. 11] funeral," he says.

Bill Calhoun, vice chairman of Bethesda, Md.-based building giant Clark Construction Group, called Hackerman "a revered competitor."

Hackerman was hired by Whiting-Turner as a superintendent in 1938, after earning a Johns Hopkins civil engineering degree, at just age 19.

In a rare comment for a book on Baltimore history, he recalled his good fortune in landing there, with tough economic times and anti-Semitism limiting options, even for skilled professionals; he noted engineering peers who "sold shoes for the duration of the Depression."

By 1955, company co-founder Whiting chose him as the next CEO, at age 37.