Building Information Modeling Boosters Are Crossing That Bridge

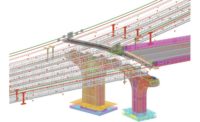

...communication tool. Brady Nadell, PB’s Doyle Drive project manager, says Caltrans requested PB and its joint venture partner, Arup, design using BIM early in design. Caltrans is engineering the new road and bridge, while PB and Arup work on two tunnels. Caltrans submits 2D plan sets to the team for creation of 3D road models, and 4D models to represent scheduling for contractors. As far as BIM goes, “Doyle Drive is a real quantum leap,” Nadell says.

Changing an overall DOT culture takes time, says Dunrud. “It’s not like the private world, where you get a bonus for finishing quickly,” he says. But public demand for agencies to deliver projects faster and cheaper may help change that.

Open BIM standards from vendors would also help, adds Arun Shirole, senior vice president of civil engineer Arora and Associates PC. Shirole and Stuart Chen, a professor at the State University of New York at Buffalo, coined the term “BrIM” for bridge information modeling. Their team is working on a federally funded project to study integrated bridge project delivery and life-cycle management. “The idea is not [to use] the most optimal software,” he says. “Our goal is to use any commercial [packages] and link them.”

While owners may seek interoperability among software brands, Bentley has acquired various bridge software products and has been working to integrate them into a complete life-cycle package. “We’ve been focused for a year and a half on this,” says Gabe Norona, a Bentley senior vice president.

The vendor says it is trying to remain open to the idea of open standards for BrIMs. “Unless we develop approaches the majority [of vendors] agree upon, we won’t turn out useful stuff,” says Jackie Cissell, a Bentley spokeswoman.

As with building BIMs, bridge designers have had compatibility issues, says Craig Finley, founder of the Tallahassee-based firm that bears his name. An example is concrete analysis software that doesn’t link with rebar programs. “If [a design-build partner is] not used to these products, it’s a problem,” he says. “You can struggle to get equal results with different models.”

Alex Harrison, senior bridge technologist with CH2M Hill, Englewood, Colo., notes different software tools from a single vendor can be incompatible. “We’re still running different programs for different things,” he notes. “As you add on more layers, it gets more complex.”

But as technology evolves, users will find that the learning curve, even when working with different software products, is not as steep, says David Fagerman, transportation technical specialist for Autodesk, San Rafael, Calif. On Doyle Drive, PB uses Bentley products for design, Autodesk’s for merging models and Oracle’s for scheduling.

Austin Commercial, which is building a $27-million checkpoint for the Phoenix Sky Harbor Airport, used BIM to help place 90-ft-long, 50-ton steel-plate girders for a terminal bridge expansion over a road and under a parking garage. “The project is vertical in nature, but with extensive foundations, [it’s] like a bridge,” says Steve Jensen, Austin’s project manager.

The complexity made it a great candidate for BIM, he adds. The challenge was developing an accurate model of existing conditions, including adjacent structures and underground utilities. “Working through these issues virtually is far better and cheaper” than solving problems in the field, he says.

Dennison hopes BIM will draw in the next generation of transportation experts. “It’s how you will attract people to this business,” he says.