Projects

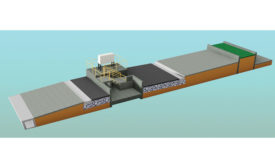

Rising Challenge

Special Report: How Engineers Are Preparing for Sea-Level Rise

From Seattle to Cape Cod, see what's being done at 18 different locations

Read More

The latest news and information

#1 Source for Construction News, Data, Rankings, Analysis, and Commentary

JOIN ENR UNLIMITEDCopyright ©2024. All Rights Reserved BNP Media.

Design, CMS, Hosting & Web Development :: ePublishing