No matter how much funding team members allocated for a self-supporting enclosure, "no one could rationalize it," says Bollman. "I can't say we ever really reached a solution, so it became a matter of stepping back and taking another look at achieving the desired effect."

"We began to put forth the idea of constructing a simpler box and reintegrating those glazed and steel elements into that base box," says Stachowiak.

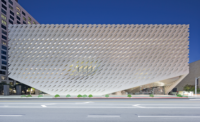

As built, the structure belies the compromises required to bring it to fruition with its unique palette of materials fully intact. Rather than being self-supporting, the steel panels work in concert as a rainscreen supported by a hybrid system of steel and concrete shear and bearing walls. While structural concrete walls support the basement and first level, the second level and roof transition to structural steel.

In keeping with Hadid's affinity for materials that express their natural character, the interior structural concrete walls are exposed and untreated, much like the stainless steel enclosure. To meet both aesthetic and structural requirements for the walls, some designed to slope to heights of 35 ft, Hadid specified self-consolidating concrete, a material well known in industrial applications, typically those requiring extensive use of resteel, but virtually unheard of for angles ranging from 50 to 75 degrees.

"It has the consistency of apple sauce, which helps promote flow around large amounts of resteel," says Bollman, who notes that very property made the material problematic for its intended use at the museum.

"The concrete exerted tremendous pressure on the bottoms of the forms, raising concerns it would cause seepage or blow out the forms altogether," says Martini. Among other tactics, contractors developed custom-hybrid forms that resist pressures at form corners.

Standards were exacting for architectural surfaces. "Specifications held imperfections to 1/32 of an inch," says Martini. Of particular concern was the prospect of bubbles—or bugs—in the slurry. "The idea was, once the forms were stripped, that was it," says Marshall. Perfecting finishes became a matter of trial and error. In all, the design and construction team tested no fewer than 50 mixes as they refined methods for concrete placement and post-placement.

As plans progressed, team members made extensive use of mock-ups, reviewing about 25 4-ft by 4-ft samples for color and finish. Incorporating lessons learned from smaller mock-ups, crews placed a pair of full-size ones, each measuring 20 ft by 35 ft.

To further ensure consistency of finish, team members derived all material from a single quarry and supplier. Mixes were stored at uniform locations at uniform temperatures, with batch trucks timed for arrival on site.

"There were times we didn't pour when we knew we were out of range," says Stachowiak. "We knew we wouldn't achieve the intended outcome.