Curtain-wall requirements were no less forgiving. To provide open, unobstructed views, Hadid specified glazing units as large as 12 ft long and 6 to 8 ft wide, some weighing as much as 1,500 lb. Rather than an aluminum subframe, plans called for anchoring the trapezoidal-shaped units directly to the structural steel, resulting in tolerances of as little as 2 millimeters.

During planning, the project team contemplated reducing the size of units for ease of fabrication, but concluded that the additional joints and structure required would compromise design intent to an unacceptable degree. Following their decision, team members launched an overseas search for a firm capable of fabricating the units.

"The U.S. just isn't equipped to fabricate and coat units that large," says Julian Barnes, Barton Malow senior engineer. After evaluating firms in Canada and China, team members awarded Bretten, Germany-based Bischoff Glastechnik a single contract for both glazing and the related structure due to the tight tolerances between the two.

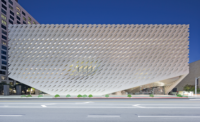

Rather than large, monolithic units, stainless-steel paneling called for "thousands of individual pieces" due to concerns ranging from aesthetics and constructibility to expansion and contraction, according to Barnes. Even after unburdening the steel of its structural role, "there was concern we might not be able to afford it," says Stachowiak.

One issue was grade. To prevent corrosion, Hadid specified 316 steel, a marine-grade material that carried a hefty price tag. Reconciling material and budget required value engineering, much of it involving reconfiguration of clips and angles to reduce the number required to mount the panels, according to Garry Hatter, Barton Malow project superintendent.

Specifications addressed only performance and aesthetic requirements, says Hatter, providing Kansas City-based fabricator A. Zahner Co. considerable latitude in detailing the corrugated panels, which resembled skewed accordions. To do so, the firm worked extensively with 3D modeling software typically reserved for the design of automobiles.

As with the concrete, team members engaged in mock-ups, from which they concluded that the machining processes employed by Zahner were better suited for square shapes than angled ones. As a result, Zahner created a 20-ft-long, 10-ft-wide custom mill to effect the V-shaped cuts required to fold metal pleats into crisp angles.

All told, "85% of the steel was prefabricated off site on the basis of construction documents," says Hatter. The remaining 15%, he says, primarily involved caps, parapets and doors.

Efforts to fabricate and install glazing initially proved more problematic. Bollman believes minimal use of caulking and gasketing between glazing and structural steel resulted in tolerances too tight to consistently meet. "Hadid likes to push the envelope," he says. "The firm envisioned a purer interface between glass and steel." Upon arriving on site "upward of 50% of the units didn't fit," says Bollman.

"There were so many variables involved," says Barnes. "In addition to tolerances, there were issues of geometry—even slight deviations in the fabrication of those trapezoidal members could impact the outcome. And very few of them were identical."