Team Building 1,397-ft 432 Park Avenue Tower Went to Extremes to Make It White

Few know more about deceptive appearances than the team producing the world's first high-strength, white-concrete, exposed-perimeter structure for the tallest residential tower in the Western Hemisphere. On the face of it, Manhattan's 1,397-ft 432 Park Avenue—the first supertower designed by Rafael Viñoly Architects PC—looks straightforward. The upended spaghetti box, enclosed and 74% complete, has no bedeviling setbacks, twists or swoops. Columns and spandrel beams form a consistent checkerboard pattern. The white color never changes. Every window is the same size.

But it is the very regular, repetitive—and white—perimeter columns and spandrel beams that had the contractors, who already were stressed by the challenges inherent in building a supertower, climbing the walls. "It looks very simple," says Justin Peters, project executive for the construction manager-at-risk, Lend Lease (LL). "It isn't."

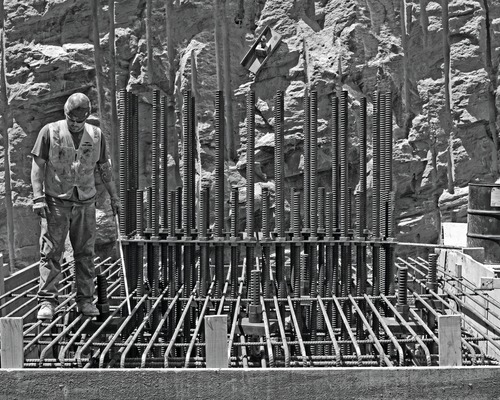

The pale complexion of the unclad perimeter columns and beams—achieved using white, instead of gray, cement—was the tower's single most mind-boggling feature. "The exterior was the make-or-break part of the job," says Peter Rodrigues, executive project manager for superstructure concrete contractor Roger & Sons Concrete Inc.

The white, high-strength concrete stacks up as the greatest challenge ever requested by a ready-mix producer, adds veteran mix developer Andreas Tselebidis, director of sustainable concrete technology and solutions for mix designer-chemical supplier BASF Corp.

White cement, which is finer than gray, changes the mix chemistry but not in a good way (see story, p. 25). Yet the self-consolidating concrete, pumped to 1,397 ft, had to pass muster in terms of strength, modulus of elasticity, fluidity, pumpability, color and appearance.

The tube's specified strength, as high as 14,000 psi, didn't help the flow. Because of the height, there were pumping challenges related to weight and time, even for the interior's gray concrete, says Kenneth Krautheim, technical director of Ferrara Bros. Building Materials Corp., the ready-mix concrete producer. The exterior was worse, thanks to the temperamental high-strength white concrete, which becomes tacky and thus difficult to mix, deliver, pump and place.

"Initially, every time we did a mock-up, the pump clogged," says Peters. "But we didn't place the first floor columns—most important because they are the most visible—until we got it right," he adds.

It took eight months to bid the concrete work and six months to get the white mix down—two months longer than expected. "It set us back, though it was before we had guaranteed a schedule," says LL's Peters.

Overall, LL says it achieved its October 2014 topping-out milestone with the help of two-shift, six-day work weeks. Initial occupancy is set for August; substantial completion is set for early next year.

Developers CIM Group and Macklowe Properties Inc., which declined requests for interviews, do not allow the building team to provide cost data and do not release sales data. Condos start at $7 million, and the penthouse sold for $95 million, a spokesman confirms.

The condominium tower contains 104 units, beginning at level 18. Up to 18, floors are devoted to retail use, residence amenities and mechanical space.

The design grew from the inside out. "We started with the core and the floor plan, rather than the height and shape," says Jim Herr, partner in charge for Viñoly.