ENR FutureTech Digs Deep Into Construction Data in Action

Conference focuses on the ways contractors, designers and owners use their data

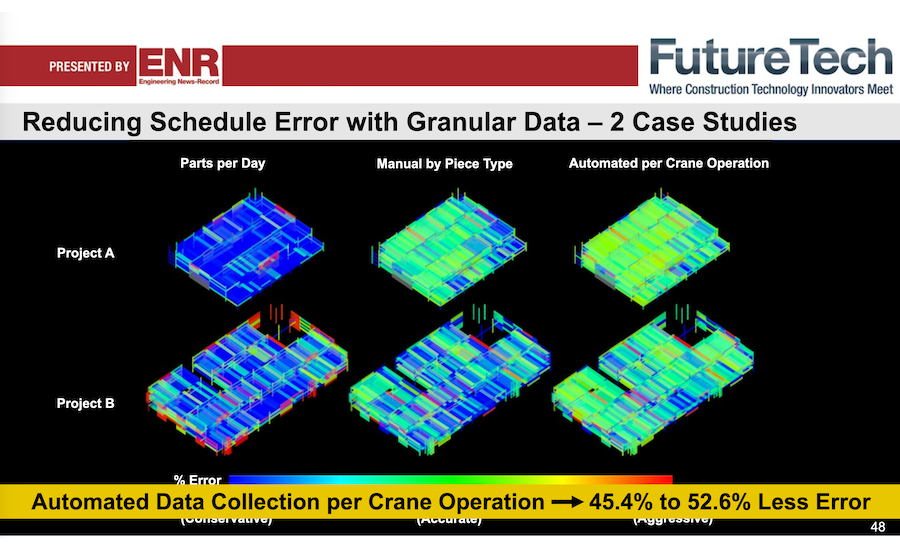

Clark Pacific was able to dramatically improve project schedules using Versatile's CraneView.

Additive construction, or 3D printing, has advanced quickly in the last decade, and is showing promise for quick construction of shelters and other emergency structures.

Day three at ENR's annual FutureTech conference was all about the data. Construction information from crane-mounted cameras and data-recording systems, parametric design programs and of course drones and laser scans are bringing more data to contractors and designers than ever before.

Better data may inform entirely new ways of building, as explored by Kurt Maldovan, global director of digital delivery solutions at Jacobs in his wide-ranging keynote on the state of the additive construction technology, also known as 3D printing.

As designers push the limits of their structures and look to increasingly distinctive shapes, the old refrain of the last few years returns: Is 3D printing ready yet?

Jacobs is supporting NASA and U.S. Army Corps of Engineers challenges to 3D print structures on Mars and is interested in moving the technology forward to other, Earth-bound applications.

While full commercialization of 3D-printed systems still remains elusive, he said that recent progress is very promising.

“A lot of work has been done in the last 10 years,” he explains. “Working out the nozzle designs for the continuous flow of materials was a game changer."

He also says the broader use of 3D printing may be closer than you think, with some firms already seriously exploring meeting building codes and structural requirements. Maldovan expects that the freedom offered by 3D printing and the chance to escape rectilinear design will be too tempting for the industry to pass up.

A potential global housing crisis could be addressed by the type of system Jacobs is working on, a data-informed additive manufactured building that can be prefabricated and assembled with as little as a 3D cementitious material "printer" and a kit of parts with instructions, he said, noting that a McKinsey Global Institute report said that by 2025, 1.6 billion urban dwellers might be struggling to secure decent housing.

“It takes six to nine months to construct the average home in the U.S.,” said Maldovan. “What if we could do it in a day?”

More Informed Crane Picks

Back on Earth, Jon Mohle, product and market manager at Clark Pacific explained how using Versatile's CraneView data capture system reduced overtime by half on the contractor's parking structure projects, just by increasing productivity.

CraneView is a sensor-laden device that hooks just below the crane's hook and has a camera that records what's happening around it. It uses machine-learning algorithms to analyze the video and automatically identify everything hoisted by the crane. It tracks every crane pick, recording it all in regular, detailed reports on crane utilization, said Versatile CEO Meirav Oren.

"We all agree, you can only improve what you measure," she said. Mohle said Clark Pacific was able to save $40,000 to $60,000 per project on six different structures using a combination of CraneView and an analysis of the data it captured.

Stanford University PhD student and Center for Integrated Facility Engineering fellow Yan-Ping Wang ran simulations based on the data to determine how to maximize the accuracy of each crane pick, then rated each recorded pick red to green. This gave Clark Pacific the granularity of feedback it needed to make better informed decisions when those results were sent to field supervisors. Mohle said Clark Pacific is now rolling out CraneView company-wide and wants to do automated field reports to give more time to project executives.

"We achieved 75 fewer minutes of idle crane time per project," Mohle said. He also said that crane operators instantly warmed to CraneView when it shortened their days and moved projects along faster.

Better Building Through Coding

Getting the right data into the right hands often requires building bridges between disparate design software systems. Representatives from BuroHappold, HOK and HMC Architects discussed how to build those bridges. A key is fostering collaboration across disciplines through the common language of code.

Kayleigh Houde, computational community leader at BuroHappold, discussed the firm’s Building Habitats and object Model (BHoM), coded not only by software developers, but by engineers from a variety of disciplines. “BHoM has allowed a lot of trans-disciplinary skill sharing. Once you realize that a duct and a beam are not that dissimilar to each other, it allows you to borrow concepts from other ideas or start to link different toolkits together,” says Houde.

HOK senior structural engineer Mark Hendel discussed HOK’s Stream tool, which links several applications to provide real time construction design and performance feedback. Stream has been used to rapidly prototype the Halo Video Board at Atlanta’s Mercedes-Benz stadium, the largest video board in the U,S,

Tadeh Hakopian, design technology manager at HMC Architects, evangelized for analyzing and leveraging your talent pool. The firm is prototyping a tool that uses employee data to find the right person for a given task, based on that data. “We can create a profile for [an employee] that a project manager can use ... to fill out a team better, ” he said, describing the software tool his firm custom built for the job.

Building Trust With Data

One of the key issues in any data handoff is trust. Can field personnel trust the numbers other project team members are giving them? Are the numbers being recorded on site accurate?

One potential solution is the use of a blockchain, or digital ledger. In popular culture, blockchain technology is often conflated with cryptocurrencies such as Bitcoin, but the technology can have practical uses for verifying deliveries and work completed, according to the panelists in the “Smart Contracts and Blockchain” session.

“We’re looking to bridge the trust gap between transaction parties,” said Michael Matthews, senior vice president at Data Gumbo. “As long as the parties agree on the data sources … a blockchain can be used for storing information.”

Data Gumbo has worked with clients in the oil and gas industry on using blockchains to verify deliveries of materials to drill sites, even confirming personnel arrivals and departures on offshore rigs. The system allows for automatic upload of data from sensors or automated reports into the private blockchain, or digital ledger, which keeps an immutable record of of all the incoming data. As the contractor and owner can now get same-day updates on all incremental work performed, payment times can be dramatically decrease, said Matthews.

The “smart contracts” that use blockchains to confirm work completed can even be slightly modified versions of standard contract documents in construction, according to Scott Greer, partner at the law firm King & Spalding.

“At first I thought smart contract was a separate contract document, but that’s not the case,” he explained, adding it's just a matter of a few addendums to model contract documents. If anything, the hardest part is deciding what automatic reporting functions should be sending data to the blockchain. “Make sure what you want to automate is something the computer can actually do,” added Greer.