The widespread return to in-person learning across Boston Public Schools on March 1 marked the first time many students and teachers entered aging school buildings undergoing up to $20 million in virus-related renovations and upgrades.

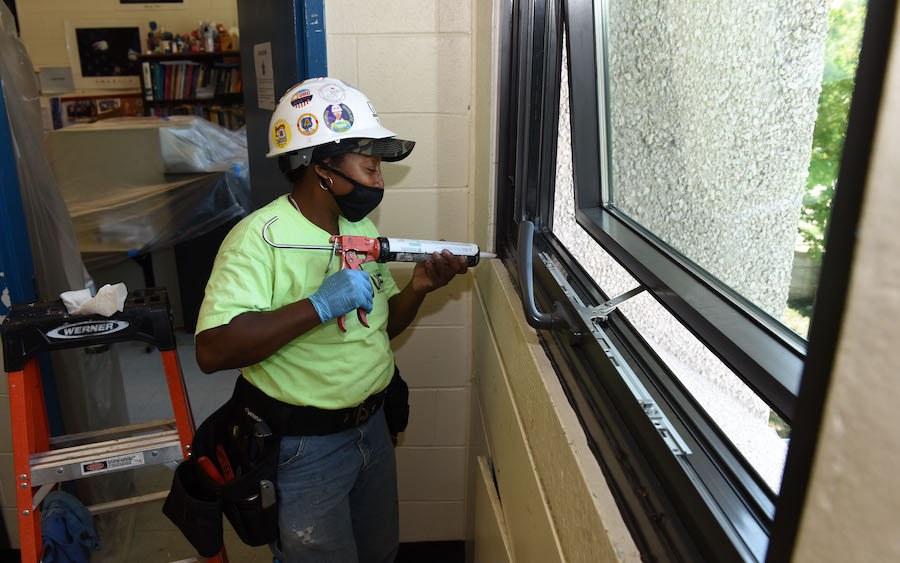

Workers installed glass and clear dividers between desks since the majority of the district’s approximately 50,000 students began learning remotely at the start of the pandemic in March 2020. After inspecting more than 27,000 windows, the district is polishing off a $7 million project this week to repair or replace more than 7,000 windows, according to the district’s spokesperson, who also noted that crews upgraded heating, ventilation and air conditioning filters and systems.

Brian McLaughlin, district director of facilities and capital planning, said not “having to work around students helped” crews deliver work faster across the school system's 123 school buildings. To date, the district has spent $10 million on COVID-related work, according to a spokesman for the school district.

Pre-school and kindergarten through Grade 3 students began a hybrid schedule on March 1, adding nearly 8,000 students to buildings already occupied by nearly 7,000 high priority students. Students in grades 4 through 8 will return on March 15, and all other students on March 29. Boston Mayor Martin J. Walsh noted declining coronavirus cases and hospitalizations in a Feb. 25 briefing. The city’s seven-day average positivity rate of 3.4% was the lowest since October.

Boston schools reopened the same day Gov. Charlie Baker (R) loosened restrictions on indoor performance venues and restaurants, although critics note Massachusetts has reported 51 cases of the UK variants and two cases of the South African strain as of Feb. 28. The state had more than 550,000 total COVID-19 cases and 15,796 deaths as of Feb. 28, says the state Dept. of Public Health, with some 1.7 million people now vaccinated.

Clash Detection

After the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention issued guidelines on how to reopen schools, Massachusetts Education Commissioner Jeff Riley said Feb. 23 that he wants all elementary students to return to in-person learning five days a week, starting in April.

Teachers’ unions, including the Boston Teacher’s Union, panned Riley for moving forward unilaterally. BTU also clashed with city school officials over the district's original reopening plan in a lawsuit filed last year. The city ultimately halted the plan due to increased COVID-19 spread.

But as high-needs students were set to return to in-person learning in the fall, the city teacher's union released a report decrying school air quality. Authored by the Massachusetts Coalition for Occupational Safety and Health, it called on the district to test classroom ventilation in 93 schools without heating, ventilation and air conditioning systems. School building windows and fans, ventilation and air filtration systems were in poor shape, according to the report, which also was critical of indoor air quality inspection data and cleaning protocols.

But union President Jessica Tang recently told the Boston Herald that the district has made significant improvements since the report was released, giving “credit where credit is due.”

Centuries in the Making

While unveiling in 2017 a $1 billion, 10-year master plan for public school facility upgrades, Walsh noted that more than 60% of buildings were built before World War II and less than half had been fully renovated. Eight schools were built in the late 1800s, according to a facilities assessment by Symmes, Maino & McKee.

The challenge to repair and upgrade schools varied from building to building. Toilet and ventilation systems didn't meet code requirements and needed to be replaced, according to the BuildBPS 10-Year Educational and Facilities Master Plan, released in 2017.

The school system received $32.3 million in supplemental funding as part of the CARES Act school emergency relief fund to address COVID-19 impacts. It will receive about $123 million of new funding from the act's 2021 successor legislation.

Also, to ensure compliance with CDC guidelines and to continue repairs at all schools, the school district ordered and installed 4,785 plexiglass dividers. as well as vinyl barriers, 6,000 fans and 63,475 COVID signs for all buildings, according to Superintendent Brenda Cassellius.

Buildings fall into one of three categories: those with central HVAC; those with steam heat and limited mechanical ventilation; and those with steam heat and no mechanical ventilation.

The district says while there is no COVID-19 specific air quality testing available, the district's testing program begun in September continues. In buildings with steam heat and limited ventilation, air quality is tested by measuring carbon monoxide, carbon dioxide, temperature, volatile organic compounds and total dust.

As the majority of students learned remotely during the last year, window inspections and repairs were made in two phases. Under phase one, at least one window opened in every classroom in each building. Phase two, included cleaning and lubricating 12,000 windows. Of that 12,000, more than 7,000 windows were identified for repair.

Classroom temperature settings have been raised and boiler runtimes increased to provide heat when windows are opened. All exhaust fans are running 24 hours a day, seven days a week.

The district also secured 7,500 air purifiers for classrooms in non-HVAC buildings and for additional spaces in HVAC buildings. HVAC systems achieve air flow via regular operation, according to a school system statement

Capital Gains

After Boston became the first large U.S. city to stop construction to prevent COVID-19 from spreading, three of the district’s largest capital projects were initially affected. Contractors had to leave job sites at Boston Arts Academy, Madison Park Technical Vocational High School and the John D. O’Bryant School of Mathematics and Science

Before work could resume in May, “contractors working on all projects had to submit a COVID-19 safety program, so they could get out there with the labor force to support the needs,” McLaughlin said.

While Madison Park received a $3.5 million roof, a $989,000 electrical system and a $5.5-million fire alarm upgrade, crews replaced 166 windows installed more than four decades ago at the O’Bryant School, McLaughlin said. Windows that did not contain hazardous materials were recycled, with others that had hazardous materials like caulking, paint or insulation were disposed of, he said.

About $1.1 million of new windows at O’Bryant “will be a vast improvement in energy efficiency,” McLaughlin said. They will have 1-in. thick insulated glazing with argon gas and passive Low-E – a pyrolytic coating applied to glass to reduce solar heat gain within the building, he added.

The project also includes a $7.69-million, 20,000 sq ft locker room upgrade expected to be completed in March 2022.

An estimated $6 million in electrical improvements at Madison Park are still being scheduled.

Seventh-Inning Stretch

Work on Boston Arts Academy—a new high school being built across from the Fenway Park baseball stadium—was delayed by the pandemic and other unforeseen site conditions, but the $125 million facility topped off in February.

After the original school building was demolished in January 2019, about $3.6 million was added to the original $1.05 million estimate for hazardous materials abatement due to “unforeseen below grade asbestos, lead, and petroleum contamination,” McLaughlin said. The Boston Arts Academy Foundation raised funds through philanthropic sources to bridge the gap. The new facility will expand the school from 121,000 sq ft to 153,500 sq ft, enabling a 15% enrollment increase.

When construction is completed in 2022, the new school will include a glass and brick façade, theatre marquee, rooftop green space and 500 seat auditorium.

This story was updated with new information on March 8