Digging Deeper | Geothermal Energy Systems

Towers Rise Atop Largest NYC Geothermal Energy System

The 463-unit, two-tower project will take advantage of its Coney Island site near the ocean to include what will be New York City’s largest geothermal energy system when complete.

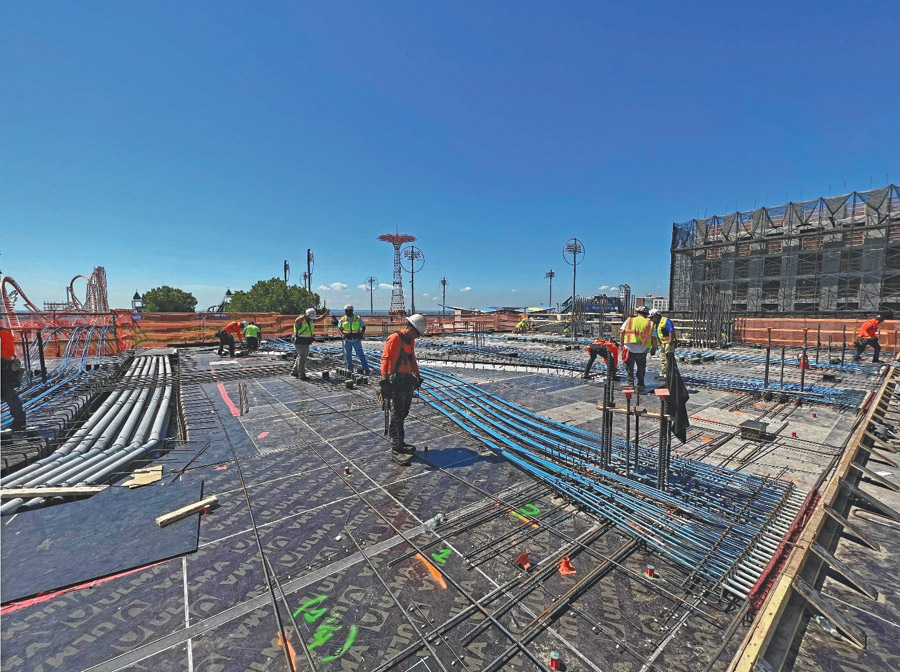

Photo courtesy LRC Construction

The most striking feature of Coney Island’s newest attraction—a 471,000-sq-ft, 463-unit residential complex set to open one block from the Brooklyn beach in 2024—won’t be visible to visitors, residents or aficionados of hot-dog-eating contests. That’s because most of what will soon be New York City’s largest geothermal heating and cooling system at the 1515 Surf Ave. residential complex is underground.

Geothermal technology was not in the original plans for LCOR, a Berwyn, Pa., multifamily developer, when it acquired a 1.5-acre parking lot through a 99-year ground lease in 2019. But it became a viable option as the developer sought ways to make the two-tower complex sustainable for the long haul, says Anthony Tortora, senior vice president of the firm, which is majority-owned by the California State Teachers’ Retirement System.

“We spent the better part of a year and a half investigating the constraints and challenges,” he says. “That this site was so large and was close to the ocean presented itself as a unique candidate for geothermal.”

The complex’s dual-level pool deck has views of the iconic Coney Island amusement park and the Atlantic Ocean. The project, 1515 Surf Ave., will set a city size record for geothermal energy use when it opens in 2024 (see below)

Renderings courtesy Studio V Architecture

Geothermal systems enable buildings to limit use of carbon-emitting HVAC equipment, such as natural gas-fired boilers, by providing heating and cooling as well as energy to run heat pumps. Wells deep under-ground use the earth’s ambient temperature to warm or chill liquids. That heat energy then transfers throughout the structure via pumps and pipes, which also redirect waste heat as an additional energy source.

Once the 1515 Surf Ave. team chose geothermal, it became clear it would be no average application.

“This will be the largest geothermal project in the city by a factor of two. No. 2 is a little project called St. Patrick’s Cathedral,” says Jay Valgora, principal of project architect Studio V—referring to the iconic Manhattan church’s heating and cooling system installed in 2017 as part of a $200-million renovation. But the Brooklyn project team still faced a big early challenge after breaking ground last November—threading 153 wells into the site footprint among 621 foundation piles that will support the sprawling structure.

Read this related story: US Energy Dept. Wants More Geothermal Power Development

“It became a big geometry puzzle because the wells have to be a certain distance apart from each other, and the wells and the piles also have to be a certain distance from each other,” Tortora says. “Then it’s the actual logistics and execution of that construction. How do you layer in your trades and execute your foundation, geothermal and excavation work?”

“This will be the largest geothermal project in the city by a factor of two. No. 2 is a little project called St. Patrick’s Cathedral.”

—Jay Valgora, Principal, Studio V

The team ended up subdividing the site to sequence multiple trades on different stages, Tortora says. “We had geothermal rigs as well as pile rigs on site at the same time, and it was all about how those rigs moved around the site in an efficient way,” he adds.

Executing construction—and siting wells every 20 ft across the foundation’s footprint—required field adjustments along the way, says Raymond Johnson, executive vice president of engineering and construction at Ecosave, an energy efficiency consultant on the geothermal system design. Test borings helped the team determine not only the ground’s thermal properties but also the soil’s structural stability, he says.

“The soil wasn’t consistent throughout the site,” he says. “We went through a learning curve to determine the most advantageous way of drilling.”

Most of the site has suboptimal soil, which made drilling wells challenging, says Pete Palazzo, president of LRC Construction, the construction manager. The team dug each well 500 ft deep, while piles went down 40 to 50 ft. “This system was installed basically in sand,” he says.

The project team threaded 153 geothermal wells into the site footprint in between 621 foundation piles that support the sprawling structure.

Photo courtesy LRC Construction

Coney Island Comeback

When real estate brokers brought the property to market several years ago, LCOR saw potential, Tortora says. “We loved the fundamentals. The area was recently rezoned, it had proximity to mass transit and to the beach, amenities and the opportunity for scale,” he says.

It also offered the unique chance to support the historic neighborhood’s comeback. “We’re really excited to be part of the revitalization of Coney Island,” Tortora says.

The 1515 Surf Ave. campus will merge two structures on a site bordered by Surf and Mermaid avenues and by W. 15th and W. 16th streets. A 26-story tower facing the ocean with the main residential space is at the corner of Surf and 16th, sitting atop an L-shaped seven-story base along the property’s eastern half. A 16-story tower housing many of the project’s 139 affordable housing units is on the corner of Mermaid and 15th above a six-story base along the western side.

The masonry facade design “is a nod to Coney Island’s past and to neighborhood buildings, but with a modern flair.”

—Anthony Tortora, Senior Vice President, LCOR

The overall project features 386,000 sq ft of residential space, 11,000 sq ft for retail use and 74,000 sq ft for a 233-space, above-ground garage. Amenities will include a heated rooftop pool and deck atop one low-rise base; a 20,000-sq-ft landscaped green roof above the garage; an indoor gym, indoor basketball and handball courts; and various tenant lounges and co-working spaces.

Studio V’s masonry facade design fits with the district’s character, Tortora says.

“It’s a nod to Coney Island’s past and buildings in the neighborhood, but with modern flair,” he says. The team started on the foundation and geothermal sitework last fall and winter, completing it in stages earlier this year, says Palazzo, whose firm is overseeing a $170-million construction budget, according to its website. Project participants decline to confirm its full cost, which also was not disclosed in public records or in other media reports.

By late summer, the team was finishing garage and eastern low-rise base slab pours as well as erecting the ninth and 10th floors of the shorter tower and third and fourth floors of the taller one. It should top out on the 16-story tower this fall and the taller structure early next year, fully enclose by next spring and complete interiors and finishes through the rest of 2023, Palazzo says.

The structure is among a growing number of projects in New York City that are incorporating geothermal energy to meet a new city law that sets carbon emission caps on buildings larger than 25,000 sq ft by 2024.

Photo courtesy LRC Construction

Groundbreaking Geothermal

Geothermal technology has made inroads across New York, with the state Dept. of Environmental Conservation having registered 128 projects with wells deeper than 500 ft, including 81 in New York City, and numerous others with shallower wells, a spokesman says. While that includes iconic city sites such as the Brooklyn Children’s Museum and Bronx Zoo’s Lion House, most only use geothermal energy for partial needs or on a small scale.

The geothermal system at 1515 Surf Ave. is notable not just for size but also because it will avoid the need for fossil-fuel-powered heating and cooling equipment—helping meet the city’s new Local Law 97 carbon emission caps on buildings larger than 25,000 sq ft by 2024.

“The market is now focused on it because there are real financial consequences to building the usual systems that run off natural gas or other combustible fuels,” Tortora says. The system, while adding 1% to the project’s cost, will reduce its carbon footprint by more than 60% compared with traditional energy, he says. “We thought it was worth the investment up front,” Tortora says.

With suboptimal soil for drilling wells and piles, “this system was installed basically in sand.”

—Pete Palazzo President, LRC Construction

The system also is helping pioneer larger scale applications. Ecosave assisted LCOR in winning a grant last year from the New York State Energy Research and Development Authority under a $4-million pilot program to build community heat pump systems that can spread across multiple properties.

The 1515 Surf Ave. system showcases such possibilities, says Ecosave CEO Marcelo Rouco. “We’ve shown that geothermal can be done for multiple buildings, for a campus, for a neighborhood,” he says. “That will accelerate its usage.”

It also advances a priority for the Mayor’s Office of Climate and Environmental Justice, which is sponsoring a district-scale geothermal demonstration project.

“To advance this work, the city is undertaking a feasibility study to select a potential demonstration project site or set of sites that could benefit from a district geothermal system, connecting multiple buildings with shared infrastructure to maximize the environmental benefit,” a spokesperson says.

Amenities will include a heated rooftop pool and deck atop one building and a 20,000-sq-ft landscaped green roof above the outside 233-space garage.

Photos courtesy LRC Construction

Innovative Technology

The 1515 Surf Ave. geothermal design was challenging due to building size and height and because systems must redirect excess heat generated, Rouco says. “The taller the building, the less square footage of ground we have, the more we have to find other things to offset heat rejection,” he says.

“We’re essentially sequestering carbon dioxide as a refrigerant and using it rather than typical freon. It’s a more efficient technology.”

—Raymond Johnson, SVP, Ecosave

Among project innovations is the use of excess energy to heat the pool and domestic hot water for the building. Hot water heat pumps will use carbon dioxide as a refrigerant, a new technology, says Ecosave’s Johnson. “We’re essentially sequestering CO2 as a refrigerant and using it rather than typical freon,” he says. “It’s a more efficient technology, and it’s not a refrigerant that’s going to be canceled out or discontinued in use because of impact on the environment.”

Such innovations are also a design victory, Valgora says. “The idea that you could use a swimming pool overlooking the beach in Coney Island as a sustainable feature–that’s a fantastic thing,” he says.

The experience also has also reshaped LCOR’s approach, Tortora says. “This was really the first project on which we were able to study geothermal at a detailed level and incorporate it into the design of the building,” he says. “It’s quickly becoming our standard. Any new project we look at we assess the viability of a geothermal system. It’s the way our industry is headed, and for the right reasons.”

The project team should top out on the 16-story tower this fall and the taller structure early next year, fully enclose by spring and complete interiors and finishes through the rest of 2023.

Photos courtesy LRC Construction

Sustainable Features

Other sustainable features at 1515 Surf Ave. include using post-tensioned concrete for the superstructure, a lighter and more efficient technology that still is not used widely in New York City, Palazzo says.

That also benefits the design, Valgora says. “Post tension allows for greater spans,” he says. “It’s kind of an integrated sustainable solution—less concrete, less material, more open space for the piles and more room for the wells for heat rejection. It’s really all tied together.” The project also has green roofs and uses natural, low-VOC and recycled materials, Valgora says.

One sustainable design feature is resilience—critical in an area that floods with up to 4 ft of water in extreme storms, he says. “We’ve done a series of things to elevate the whole building by nearly 7 feet, which exceeds the city code,” he says. “We also created a series of features that make it still very accessible, so it doesn’t feel like it’s up on stilts.”

Those include plants, landscaping, staircases and porches at lower levels that can weather flooding, Valgora says. “It takes into account sea-level rise and climate change,” he says. “That’s actually baked in while it’s restoring and recreating a neighborhood.”