As drone photography, reality capture and site scanning continue to grow in importance for contractors, so have the skills of the pilots.

Until the National Institute of Standards and Technology released its first standard for the performance of small unmanned aircraft systems (SUAS) in December 2018, there was nothing for the top guns of construction to measure their skills against.

On Aug. 29 at its Deerfield, Ill., campus, the Oracle Industry Lab held what’s believed to be the first construction drone operator challenge based on NIST’s standards.

“It’s NIST. It’s a standard we can compare performance to objectively,” said Gregg Schkade, senior capture, lead pilot and data lead at 3D reality-capture specialists VTS, based in Brighton, Mich. Schkade competed with three other drone pilots at the Oracle event: Bryan Prignano, technical services project manager at Pepper Construction in Chicago; Keaton Denzer, chief UAV pilot at Bechtel Equipment Operations in Houston; and Antoine Tissier, drone operations manager for Clayco’s VDC team in Chicago.

The course measured both the drones’ system capabilities and the proficiency of the pilots in carrying out five basic maneuvers, including accurate landing, vertical climbing and straight-and-level flying. Competitors also had to perform functionality tests such as 180° orbits of buckets with printed-out targets inside. These acted as stand-ins for objects on site that needed to be photographed as part of documenting work progress or quality control. Capturing all of the necessary photos and navigating the course was timed by scorekeepers.

“[Contractors] use drones for key use cases related to safety and productivity,” said Burcin Kaplanoglu, vice president of innovation at the Oracle Industry Lab. “The future is bright. As we get more autonomous operations and [use] human pilots less, [we can] focus on data collection and the use of artificial intelligence and machine learning.”

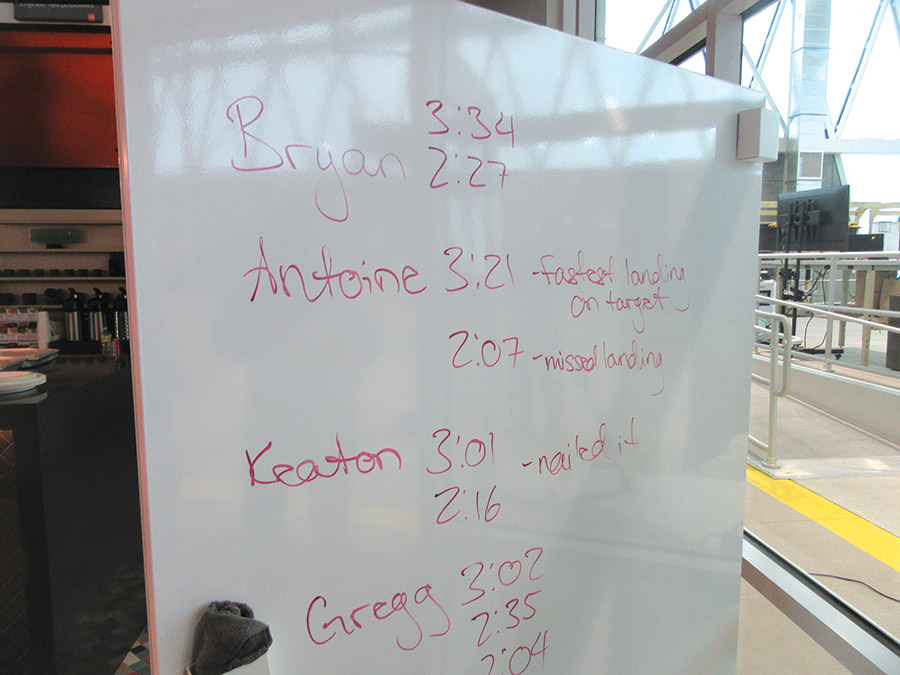

Oracle’s construction drone challenge was friendly, but performance times were recorded.

Photo by Jeff Yoders/ENR

For the challenge, the 30,000-sq-ft lab was turned into a drone racecourse with nine scannable target stickers in buckets in three ground positions and four more mounted on a structural steel frame meant to represent iron work in need of drone inspection. After scanning the targets and performing 180° spins, the four pilots had to race back to the starting line and land their drones in the target where their run began. No style points were awarded for keeping the drone within the target circle.

As the four drone pilots went through the course, certain characteristics of the machines became apparent. Schkade’s drone could spin faster than the others with collision detection turned off, but his Autel Robotics EVO 2 was not as fast on straightaway flying as the other three pilots’ DJI Mavic devices. All four completed the course in about two minutes.

While all of the pilots enjoyed the friendly competition, they said the programming of drones for inspections, site scans and other important construction tasks can and should be automated, preferably to rigorous in-house standards like they have in their own firms. Schkade said 5G network coverage helps for larger site scans where lots of data needs to be recorded, but 5G isn’t reliably available outside of major cities.

Confined spaces on sites also present challenges for drone pilots, they said. And those aren’t easily replicated for practice, even by the standards of NIST’s tests.