The World's Biggest Supercranes

At least two supercranes are busy in the nuclear sector. Two examples of the Bigge 125D AFRD, put into duty this year, can be found on nuclear powerplant sites in the U.S.: Plant Vogtle, near Waynesboro, Ga., and V.C. Summer, near Jenkinsville, S.C. The Shaw Group, which is managing both plant expansions, purchased two machines costing more than $50 million each.

Officially, the crane is now called the Shaw HLD 125, or the Heavy-Lift Derrick.

"When you buy a car, you can put whatever name you want on it," explains R.M. "Monte" Glover, senior vice president of Shaw and consortium general manager for the Vogtle expansion.

The 6,800-tonne supercranes are the result of a request for proposals that Shaw put out to speciality rigging companies in advance of the job. "We were looking at different technologies out there, and we looked first and foremost at safety," Glover says. "We asked, 'Has lifting technology evolved in the last 30 years?' The answer was no."

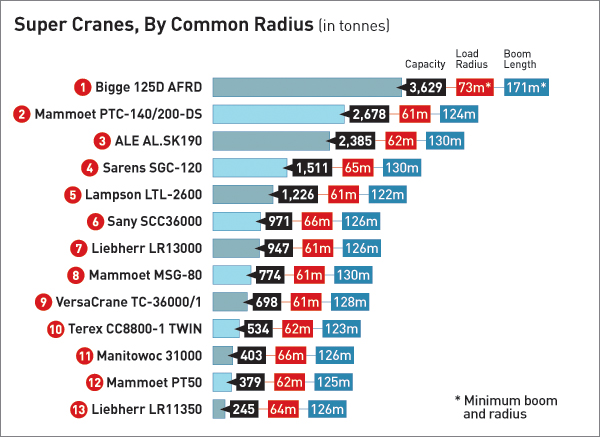

Shaw's requirement was fairly simple: It wanted a machine that didn't have to be moved around on the jobsite. Four bidders offered designs, and Shaw picked a design from San Leandro, Calif.-based Bigge Crane and Rigging Co., a longtime speciality contractor and crane dealer. Standing more than 170 m tall and situated at the center of the jobsite, the cranes can cover both AP1000 reactor buildings during the life of the projects. Each crane will be called upon to lift hundreds of modules weighing up to 1,200 tons at a 122-m radius.

"The crane is up and operational, and it's been through all the load testing," Glover says. "It's quite a piece of machinery."

Aside from Vogtle and Summer, has the slowdown in nuclear construction created less demand for these supercranes? Experts say the machines are finding plenty of work in other industrial environments. Aside from powerplants, you're likely to find supercranes working at shipyards, refineries and oil-platform fabrication facilities, says Pete Ashton, vice president of Bigge.

"What's driving the marketplace to find bigger cranes are heavier capacities to handle these large modules," says Ashton. Speed of construction and safety are two factors driving this trend.

Stick-building "results in an exposure and expense to the contractor," says Joe Collins, heavy-lift manager at Becht Engineering, which helps owners plan extreme lifts. "But more than anything, it is exposure to fall hazards and all the things that are associated with working at heights."

More of these projects are opting to "prefabricate large, extremely heavy modules on the ground level," Collins explains. "We pick it and set it, and the crane goes away."

rruggle, I think you have missed the point of this story—the information here is the result of countless hours of research, interviewing experts, consulting with engineers and studying ...

Thank you Mr Vanhampton for an article I consider one of the more solid articles<br/>appearing in ENR. I do appreciate the work you put into the article.<br/><br/>It is the translation ...

appearing in ENR. I do appreciate the work you put into the article.

It is the translation of 2500 in one system of units to 2268 in another system of units

I object to. I would round 2268 to 2300 so there would not be spurious accuracy. More

importantly with fewer digits there is a lot less chance of getting the number wrong and

here any transposition error is on the side of danger eg 2628 for 2268.

If concern is felt that 2300 is larger than 2268 perhaps a standard can be written so there

is rounding down ( the official name for this is truncation and truncation has the additional

benefit that it is less error prone than rounding).

Flatly put, not too diplomatically put, all the experts you consulted on the conversions

are wrong. My guess is that they just did not give the matter the attention it deserves.

Again I want to thank you for a very worthwhile article.

Sorry rruggie, it appears to me that you are making an unverified assumption. Not all zeros are insignificant, and just because a crane’s capacity is named to a rating of so many hundre...

Since the load limit is essentially a guarantee, or a safety limit, it appears to me that the limitations on the limit are the accuracy of the field measurements of load amount, lift radius, and similar factors. In this case, the comparison numbers are assigned, not measured, so they have no inaccuracy. You may argue that no one will measure the loads that accurately in the field, but that does not make the rating comparisons wrong. In theory, and I believe in fact, they are as accurate as your field measurements, and different applications will have different accuracies in the field.